Abstracts - Centro de Estudos Sociais

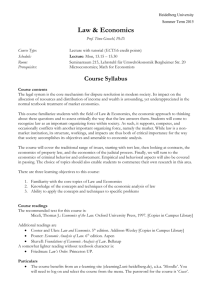

advertisement