Reclaiming the Great Khan for History

advertisement

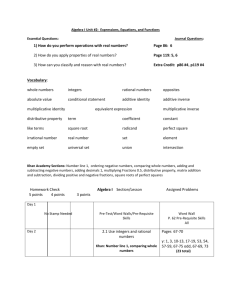

4A • Friday, March 8, 2002 SPARKS TRIBUNE Opinion Reclaiming the Great Khan for History Dennis Myers V ietnam resister David Harris once pointed out that there is a difference between idols and heroes. Those who idolize figures like Elvis Presley or Theodore Roosevelt end up missing (or misunderstanding) the real meaning of those personages. The focus on the personalities obscures their important roles in music history or U.S. history. Heroes serve a more useful purpose. From heroes we get the gift of good example, something to which we can aspire, someone who shows us that it can be done. Atlanta publisher Ralph McGill once said that no region has been so ill served by its leaders as the U.S. south. Many of its leaders called on all the worse impulses of the community, giving the public too little reason to believe there was another way. In popular culture, Islam is a caricature. Journalism and politicians have learned the skill of pitting us against Muslims by emphasizing all the worst events and figures of Islamic history and by attenuating the complexities of Islam from our knowledge, the admirable figures of the faith from our view. Imagine if Gandhi were unknown to us. Think how much his life and example have leavened our view of Hinduism. Imagine how distorted our view of that faith would be if we did not have him as a bridge to understanding. We would be susceptible to political and journalistic characterizations of Hindu militancy as typifying the entire creed. Which raises the question of why Ghaffar Khan is unknown to us. The Taliban is mainly Pathan. So was Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan. The Pathans have for centuries been known as fierce warriors (Kipling wrote admiringly of their prowess). Ghaffar Khan was a monumental figure in the history of nonviolent achievement, an equal of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin King. Many people equate nonviolence with pacifism. Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr once admitted that he had suffered from such confusion. In the forward to a collection of Dr. King’s anti-Vietnam War essays, Niebuhr wrote, “I think, as a rather dedicated antipacifist, that Dr. King’s conception of the nonviolent resistance to evil is a real contribution to our civil, moral, and political life.” Ghaffar Khan led Pathans from militarism to nonviolent direct action. In 1930, after an Indian declaration of independence, Ghaffar and his followers, the Servants of God, set the city of Peshawar on its ear with nonviolence. The British had never seen anything like it, least of all among the ferocious Pathans. When a group of resisters was fired on, according to one account, the wounded fell down and “those behind came forward and with their breasts bared, exposed themselves to the fire...so that some got as many as 21 bullet holes in their bodies, and all the people stood their ground without getting into a panic.” Awed and inspired by the courage of the resisters, a renowned British regiment refused orders to participate further in the slaughter. The regiment’s nonviolent example, in turn, inspired more nonviolent resistance in the populace. Citizens endured violence, arrest, imprisonment, torture, inflicting defeat after defeat on the British and made Pathans the dominant force in the region. Ghaffar became known as the Khan of Khans. As the British were being driven out of India, London wanted the nation split in two to create from the Pathan region a ferocious Muslim barricade, exploiting Pathan military skill to combat any southern advance by the Soviet Union (so many of the world’s modern mistakes trace their origin back to irrational anti-communism). For almost 20 years, the Servants of God controlled the northwest region, defying and frustrating this western scheme to invent another nation. And they did it peacefully. Ghaffar’s followers swore an oath: “I shall never use violence. I shall not retaliate or take revenge, and shall forgive anyone who indulges in oppression and excesses against me.” That the Pathans with their brutal culture could so easily adapt to nonviolence — and succeed at it! — mystified Ghaffar Khan himself. “I started teaching the Pathans nonviolence only a short time ago,” he told Gandhi. “Yet in comparison the Pathans seem to have learned this lesson and grasped the idea of nonviolence much quicker and much better than the Indians...How do you explain that?” Gandhi responded, “Nonviolence is not for cowards. It is for the brave, the courageous...” The Pathans’ territorial gains were lost in negotiation — India was partitioned and Pakistan created. In the ensuing years, though he lived until 1988, Ghaffar Khan vanished from view, expunged from the history he did so much to make. “[I]t all seemed written on water,” his biographer Eknath Easwaran wrote of the way this magnificent story was erased from our planet’s history. Gandhi and King are remembered; Ghaffar is forgotten. Since the beginning of the Afghan war (the Pathan region straddles the Pakistan/Afghan border), in spite of Ghaffar’s direct relevance to present events, I have seen only one mention of him in U.S. journalism, a New York Times essay by Karl Meyer — and it referred to Ghaffar as a pacifist. Even in Pakistan, Ghaffar’s role in national history has been diminished and trivialized. As Timothy Flinders wrote in the afterword to Nonviolent Soldier of Islam, a biography of Ghaffar Khan, “True nonviolence did not issue from weakness but from strength. It was a matter of the powerful voluntarily withholding their power in a conflict, choosing to suffer for the sake of a principle rather than inflict suffering — even though they could.” (I very much recommend this biography, which is available from Sundance Books. If there are no copies left in stock, Sundance can get copies in 24 hours.) The obliteration of Ghaffar Khan from history has two consequences. Those of us in the west are robbed of history that would conquer our stereotypical view of Islam. And the heroic example of Ghaffar Khan could have given Muslims an alternative to those leaders who appealed to their worst instincts. The director of Jerusalem’s Palestinian Center for the Study of Nonviolence has written, “The life of Khan can change and will challenge many readers in the Middle East.” It can do the same for those of us in the west — if we ever get a chance to read it. ______________________________________________________ Dennis Myers is a long-time Nevada political reporter. Copyright © by Dennis Myers (2002). Reproduced with permission. This version of Dennis Myers’ commentary was published in the SparksTribune of Sparks, Nevada [Myers, D. (2002). “Reclaiming the Great Khan for History.” SparksTribune, Friday, March 8, page 4A]. Dennis Myers also plans to make available a fuller version of the commentary.