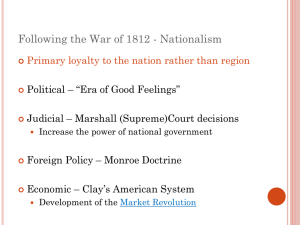

Nationalism and the Moral Psychology of

advertisement