The choice of antiepileptic medication depends on the seizure type

advertisement

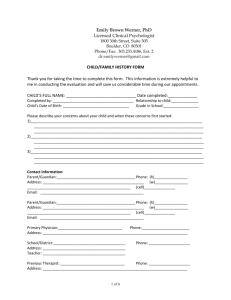

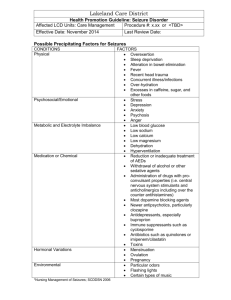

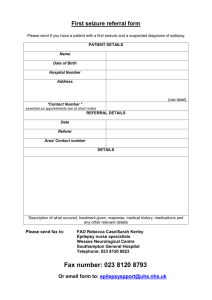

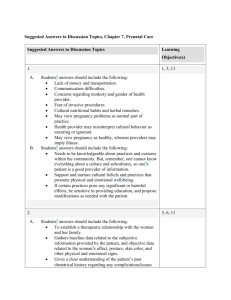

The choice of antiepileptic medication depends on the seizure type. As the foregoing literature review has shown, there are studies claiming teratogenesis for each of the major anticonvulsant medications, yet there are also studies showing that each medication individually may not be particularly teratogenic. The most important point is to control maternal seizures. There may be some additional concern for using valproate in pregnancy due to the reported increased incidence of fetal distress. It is important to note that this finding has not been corroborated in other studies. Therefore, if valproate is the anticonvulsant that works best for the patient, it should be used without hesitation. If valproate is used, the dose should be divided over three to four administrations daily to avoid high peak plasma levels. In the past, it was thought that carbamazepine was the anticonvulsant of choice and had the least teratogenic effect. As has been shown in the foregoing literature review, there are studies that report malformations with the use of carbamazepine. It is important to stress again that the anticonvulsant that does the best job of controlling seizures is the one that should be used for the patient. There is little information concerning the newer antiepileptic drugs and teratogenesis. If, however, they need to be used for good seizure control, they should be implemented as part of the patient's therapy. Folic acid supplementation should be begun before or early in pregnancy. Folic acid supplementation may help to prevent neural tube defects, which are more common in treatment with carbamazepine and valproate but have been reported in women taking other anticonvulsants. Studies have shown that folic acid may decrease the incidence of neural tube defects in at-risk women. It is important that this be implemented early in pregnancy, as open neural tube defects occur by the end of the fifth week of gestation. Furthermore, low folate levels have been associated with an increase in adverse pregnancy outcomes in women taking anticonvulsants. Anticonvulsant levels should be checked frequently after implementing or increasing folic acid administration, as it leads to lower anticonvulsant levels. A daily dose of 4 mg/day should be more than ample. Patients should also be encouraged to take their prenatal vitamins, which contain vitamin D. This is because anticonvulsants may interfere with the conversion of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol to 1-25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, the active form of vitamin D. Whether or not they ask, all mothers with idiopathic epilepsy wonder if their child will develop epilepsy. There is a surprising paucity of studies in this area. Children of parents without seizures have a 0.5 to 1 percent risk of developing epilepsy. It appears that the infant born to a mother with a seizure disorder of unknown etiology has a four times greater chance of developing idiopathic epilepsy than the general population. Furthermore, it appears that epilepsy in the father does not increase a child's risk of developing a seizure disorder. Many of the rare seizure disorders have a stronger genetic component. Care of the Patient During Pregnancy Once the patient becomes pregnant, it is of the utmost importance to establish accurate gestational dating. This will prevent any confusion over fetal growth in later gestation. The patient's anticonvulsant level should be followed as needed and dosages adjusted accordingly to keep the patient seizure free. It is a common pitfall to monitor levels too frequently and adjust dosages in a likewise frequent manner. It is important to remember that it takes several half-lives for a medication to reach a steady state (Table 37-3) . Drugs like phenobarbital have extremely long half-lives, and the levels should not be checked too frequently. If levels are measured before the drug reaches a steady state and the dosage is increased, the patient will eventually become toxic from the medication. Drug levels should be drawn immediately before the next dose (trough levels) in order to assess if dosing is adequate. If the patient is showing signs of toxicity, a peak level may be obtained. TABLE 37-3 -- ANTICONVULSANTS COMMONLY USED DURING PREGNANCY Therapeutic Drug Level (mg/L) Usual Nonpregnant Dosage Half-Life Carbamaz 4–10 600–1,200 mg/day in three or divided doses Initially 36 h, epine (Two doses if extended-release forms are used) chronic therapy 16 h Phenobarb 15–40 90–180 mg/day in two or three divided doses 100 h ital Phenytoin 10–20, total; 300–500 mg/day in single or divided doses * Avg 24 h 1–2, free Primidone 5–15 750–1,500 mg/day in three divided doses 8h Valproic 50–100 550–2,000 mg/day in three or divided doses Avg 13 h acid * If a total dose of more than 300 mg is needed, dividing the dose will result in a more stable serum concentration. At approximately 16 weeks' gestation, the patient should undergo blood testing for maternal serum marker screening in an attempt to detect neural tube defect. This, coupled with ultrasonography, gives a more than 90 percent detection rate for open neural tube defects. If the patient is difficult to scan or if she wants to be even more certain that there is no neural tube defect, amniocentesis can be undertaken. This should be considered if the patient is taking valproate or carbamazepine, as these medications appear to carry almost the same risk as if the patient had a family history of a neural tube defect.[ At 18 to 22 weeks, the patient should undergo a comprehensive, targeted, ultrasound examination by an experienced obstetric sonographer to look for congenital malformations. A fetal echocardiogram can be obtained at 20 to 22 weeks to look for cardiac malformations, which are among the more common malformations of women taking any antiepileptic medications. If fetal echocardiography is not readily available, it is reassuring to remember that an adequate "four-chamber view" of the heart on ultrasound will identify 68 to 95 percent of major cardiac anomalies.[ As previously noted, there appears to be an increased risk for intrauterine growth restriction for fetuses exposed in utero to anticonvulsant medications. If the patient's weight gain and fundal growth appear appropriate, regular ultrasound examinations for fetal weight assessment are probably unnecessary. If, however, there is a question of fundal growth or if the patient's habitus precludes adequate assessment of this clinical parameter, serial ultrasonography for fetal weight assessment can be performed. In older and retrospective studies, there appears to be an increased risk of stillbirth in mothers taking anticonvulsant medications.[] In a prospective study, however, this complication was not seen.[As previously noted, in the studies that showed an increase in stillbirths, factors such as intrauterine growth restriction or oligohydramnios were not prenatally identified. With modern surveillance and the more common use of ultrasonography, many of these risk factors can be detected before the fetus faces imminent risk. Non-stress testing, therefore, is not necessary in all mothers with seizure disorders. It should be limited to those who have other medical or obstetric complications that place the patient at increased risk of stillbirth. If at all possible, the patient should be maintained on a single medication, and drug levels should be drawn at appropriate intervals to make certain that the patient is receiving enough medication. If the patient is taking phenytoin, free levels should be obtained if possible. A drug dosage should not be increased only because the total level of drug is falling. The free level of drug may still be therapeutic. If, however, the patient develops any seizure activity, dosages should then be adjusted upward. A brief seizure during pregnancy does not appear to be deleterious to the fetus. It is best to use the lowest dose of a single medication possible that will keep the patient seizure free. This, however, must be individualized. For instance, if the patient usually experiences seizures during the day and drives, it is important to make certain that the patient remains seizure free. For this type of patient, drug dosages should be increased if levels fall. If, on the other hand, the patient only has brief partial complex seizures that do not generalize and occur only during her sleep, it is optimal to keep the medications at the lowest serum concentration that will keep her seizure free. An occasional seizure of this type would not harm either patient or fetus. The key to managing anticonvulsants in pregnancy is individualization of therapy. Early hemorrhagic disease of the newborn can occur in infants exposed to anticonvulsants in utero, and this appears to be a deficiency of the vitamin K-dependent clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X. The use of vitamin K in the third trimester to prevent hemorrhagic disease is somewhat controversial. Although some advocate administering 10 to 20 mg of vitamin K orally, daily, to mothers during the final few weeks of pregnancy, this is certainly not the standard of care. There appears to be no adverse effect of administering this vitamin, but, on the other hand, its utility has not been clearly demonstrated. Very little hemorrhagic disease of the newborn is seen today, and this is probably because most infants receive 1 mg of vitamin K intramuscularly at birth. This certainly should be given to all infants of mothers receiving anticonvulsants. Because of early discharges and the shortened time of neonatal observation, it might be prudent to check a prothrombin time on the cord blood at birth. This can be done by taking fresh cord blood and placing it in a citrated blood tube and having it sent immediately for prothrombin time. This might be especially prudent if the child is to undergo a very early circumcision. Labor and Delivery Vaginal delivery is the route of choice for the mother with a seizure disorder. If the mother has frequent seizures brought on by the stress of labor, she may undergo cesarean delivery after stabilization. Furthermore, seizures during labor may cause transient fetal bradycardia.[ The fetal heart rate should be given time to recover. If it does not, then one must assume fetal distress and/or placental abruption and deliver by cesarean section. Because stress often exacerbates seizure disorders, an epidural anesthetic can benefit many laboring patients with epilepsy. Management of anticonvulsant medications during a prolonged labor presents a challenge. During labor, oral absorption of medications is erratic and, if the patient vomits, almost negligible. If the patient is taking phenytoin or phenobarbital, these medications may be administered parenterally. An anticonvulsant level should be obtained first to help ascertain the appropriate dosage. Phenobarbital may be given intramuscularly, and phenytoin may be given intravenously. Fosphenytoin, although expensive, is available and makes the administration of intravenous phenytoin much easier. If the patient's phenytoin level is normal, the usual daily dose may be administered intravenously. The medication may only be mixed in normal saline and must be administered at a rate no faster than 50 mg/min. Fosphenytoin is easier to use. Because of the long half-life of phenobarbital, if the patient's serum level is therapeutic, a 60- to 90-mg intramuscular dose will probably be sufficient to maintain the patient throughout labor and delivery. The main problem arises if the patient is taking carbamazepine. This medication is not manufactured in a parenteral form, although extended-release forms now exist. Oral administration may be attempted, but, if the patient has seizures or a pre-seizure aura, she may be loaded with a therapeutic dose of phenytoin to carry her through labor. The usual loading dose is 10 to 15 mg/kg administered intravenously at a rate no faster than 50 mg/min. This should be effective in controlling seizures. Benzodiazepines may also be used for acute seizures, but one must remember that they can cause early neonatal depression as well as maternal apnea. Prenatal diagnostic techniques are not perfect. Even if the infant appears to have no anomalies, an experienced pediatrician should be present at the delivery of the infant born to a mother taking anticonvulsant medications. New Onset of Seizures in Pregnancy and the Puerperium Occasionally, seizures will be diagnosed for the first time during pregnancy. This may present a diagnostic dilemma (Table 37-4) . If the seizures occur in the third trimester, they are eclampsia until proven otherwise and should be treated as such until the attending physician can perform a proper evaluation. The treatment of eclampsia is delivery, but the patient must first be stabilized. It is often difficult, however, to distinguish eclampsia from an epileptic seizure. The patient may be hypertensive initially after an epileptic seizure and may TABLE 37-4 -- DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF PERIPARTUM SEIZURES Blood Protein Seizure Pressure uria s Timing CSF Other Features Eclampsia +++ +++ +++ Third Early: RBC, Platelets normal trimester 0–1,000; or ↓ RBC protein, 50– normal 150 mg/dl Late: grossly bloody Epilepsy Normal Normal +++ Any Normal Low to + trimester anticonvulsant levels Subarachnoid + to +++ 0 to + + Any Grossly hemorrhage (labile) trimester bloody Thrombotic Normal to ++ ++ Third RBC 0–100 Platelets ↓ ↓ thrombocytopen +++ trimester ic purpura RBC fragmented Amniotic fluid Shock − + Intrapartum Normal Hypoxia, embolus cyanosis Platelets ↓ ↓ RBC normal Cerebral vein thrombosis Water intoxication + Normal − − Pheochromocyto +++ (labile) + ma Autonomic +++ with − stress syndrome labor pains ++ Postpartum Normal (early) ++ Intrapartum Normal + Any Normal trimester Intrapartum Normal − Headache Occasional pelvic phlebitis Oxytocin infusion rate >45 mU/min Serum Na <124 mEq/L Neurofibromato sis Cardiac arrhythmia of high paraplegics Toxicity of local Variable − ++ Intrapartum Normal anesthetics Modified from Donaldson JO: Peripartum convulsions. In Donaldson JO (ed): Neurology of Pregnancy. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1989, p 312. exhibit some myoglobinuria secondary to muscle breakdown. The diagnosis becomes clearer over time, but in either case, rapid, thoughtful action must be undertaken. The first physician to attend a patient after a seizure may not be an obstetrician/gynecologist, and magnesium sulfate may not be started acutely. This should be remedied as soon as possible. If the patient at an earlier gestational age develops seizures for the first time, she should be evaluated and started on the proper medication. The physician must be alert to look for acquired causes of seizures including trauma, infection, metabolic disorders, space-occupying lesions, central nervous system bleeding, and ingestion of drugs such as cocaine and amphetamines. The patient must be stabilized, and the physician must make certain that an adequate airway is established for the protection of both mother and fetus. The physician should also look for focal signs that may be more suggestive of a space-occupying lesion, central nervous system bleeding, or abscess. Blood should be obtained for electrolytes, glucose, calcium, magnesium, renal function studies, and toxicologic studies, while intravenous access is being established. If the patient had a tonic-clonic seizure, and the attending physician feels that this is probably newonset epilepsy, she should be started on the appropriate anticonvulsant medication while awaiting results of laboratory studies. If she is not in status epilepticus, this medication may be given orally. If the patient presents with recurrent generalized seizures, status epilepticus, immediate therapeutic action must be taken. The drug of choice is intravenous phenytoin, as it is highly effective, has a long duration of action, and a low incidence of serious side effects. This medication should be administered in a loading dose of 18 to 20 mg/kg at a rate not exceeding 50 mg/min. Rapid infusion may cause transient hypotension and heart block. If possible, the patient should be placed on a cardiac monitor while receiving a loading dose of phenytoin. Also, this medication must be given in a glucose-free solution to avoid precipitation.[ Fosphenytoin, if available, can be given more rapidly with fewer side effects. If phenytoin is unavailable, a benzodiazepine may be used as a first-line drug for status epilepticus. These drugs, however, cause respiratory depression, and the physician must have the ability to intubate the patient if necessary when these medications are used. If these measures are ineffective, an anesthesiologist and neurologist should be immediately consulted if they are not already involved in the patient's care. Any patient experiencing seizures for the first time during pregnancy without a known cause should undergo an EEG and some type of intracranial imaging. In looking only at eclamptic patients, Sibai et al. found that EEGs were initially abnormal in 75 percent of patients but normalized within 6 months in all patients studied. While this group found no uniform computed tomography (CT) abnormalities in this set of eclamptics, they did find that 46 and 33 percent of eclamptics had some abnormalities in the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and CT, respectively. Most of the findings were nonspecific and were not helpful in diagnosis or treatment. If the physician is not certain that the patient has eclampsia, an imaging study should be part of the evaluation described above. Postpartum Period The levels of anticonvulsant medications must be monitored frequently during the first few weeks postpartum, as they can rapidly rise. If the patient's medication dosages were increased during pregnancy, they will need to be decreased rather rapidly after delivery to prepregnancy levels. All of the major anticonvulsant medications cross into breast milk. The levels vary in breast milk from 18 to 79 percent of the plasma levels.[] The use of these medications, however, is not a contraindication to breast-feeding. Primidone, phenobarbital, and benzodiazepines may have a sedative effect on the fetus with later withdrawal symptoms. Should the infant exhibit these types of symptoms, breast-feeding should be discontinued. All methods of contraception are available to women with idiopathic seizure disorders. The majority of women are able to take oral contraceptives without any adverse side effects. Oral contraceptive failures are more common in women taking anticonvulsants. This is due to the fact that all of the major anticonvulsant medications induce hepatic enzymes, which metabolize estrogen faster.[ These patients may, therefore, require oral contraceptives with higher dosages of estrogens. The amount of enzyme induction, however, varies and oral contraceptive doses must be individualized. In conclusion, the majority of women with idiopathic epilepsy will have an uneventful pregnancy with an excellent outcome. To optimize neonatal outcome, the patient should take only one medication and, when possible, use the lowest dose effective in keeping her free of seizures. It is important, though, for the patient to realize that prevention of seizures is the most important goal during pregnancy. Simple interventions such as taking folic acid prior to conception, taking prenatal vitamins containing vitamin D, and giving the infant vitamin K at birth will help to optimize the outcome. There is an increase in congenital malformations in infants exposed to anticonvulsant medications in utero. The majority of infants exposed to these medications, however, will have no malformations. With modern techniques for prenatal diagnosis, including ultrasound and α-fetoprotein determination, many of these malformations can be detected early. The majority of women with epilepsy will labor normally and have spontaneous vaginal deliveries. In short, with close cooperation and excellent communication among the obstetrician, neurologist, and pediatrician, the vast majority of these patients will have a safe pregnancy with an excellent outcome. Anticonvulsants Epileptic women taking anticonvulsants during pregnancy have approximately double the general population risk of malformations. Compared with the general risk of 2 to 3 percent, the risk of major malformations in epileptic women on anticonvulsants is about 5 percent, especially cleft lip with or without cleft palate and congenital heart disease. Valproic acid (Depakene) and carbamazepine (Tegretol) each carry approximately a 1 percent risk of neural tube defects and possibly other anomalies. In addition, the offspring of epileptic women have a 2 to 3 percent incidence of epilepsy, five times that in the general population. Whenever a drug is claimed to be a teratogen, one always can raise the issue of whether the drug actually is a teratogen or the disease for which the drug was prescribed in some way contributed to the defect. Even when they take no anticonvulsant drug, women with a convulsive disorder have an increased risk of delivering infants with malformations; this information supports a role for the epilepsy itself rather than the anticonvulsant drug as a contributor to the birth defect.[Of infants born to 305 epileptic women on medication in the Collaborative Perinatal Project, 10.5 percent had a birth defect. Of the offspring of women who had a convulsive disorder and who had taken no phenytoin at all, 11.3 percent had a malformation. In contrast, the total malformation rate was 6.4 percent for the control group of women who did not have a convulsive disorder and who therefore did not take any antiepileptic drugs. The issue remains unresolved, as patients who take more drugs during pregnancy usually have more severe convulsive disorders than do those who do not take any anticonvulsants. A combination of more than three drugs or a high daily dose increases the chance of malformations. Possible causes of anomalies in epileptic women on anticonvulsants include the disease itself, a genetic predisposition to both epilepsy and malformations, genetic differences in drug metabolism, the specific drugs themselves, and deficiency states induced by drugs such as decreased serum folate. Phenytoin (Dilantin) decreases folate absorption and lowers the serum folate, which has been implicated in birth defects. Therefore, folic acid supplementation should be given to these mothers, but may require adjustment of the anticonvulsant dose. Although epileptic women were not included in the Medical Research Council study, most authorities would recommend 4 mg/day folic acid for high-risk women. One study suggested that folic acid at doses of 2.5 to 5 mg daily could reduce birth defects in women on anticonvulsant drugs. Fewer than 10 percent of offspring show the fetal hydantoin syndrome, which consists of microcephaly, growth deficiency, developmental delays, mental retardation, and dysmorphic craniofacial features (Fig. 9-3) . In fact, the risk may be as low as 1 to 2 percent. While several of these features are also found in other syndromes, such as fetal alcohol syndrome, more common in the fetal hydantoin syndrome are hypoplasia of the nails and distal phalanges (Fig. 9-4) , and hypertelorism. Carbamazepine (Tegretol) is also associated with an increased risk of a dysmorphic syndrome. A genetic metabolic defect in arene oxide detoxification in the infant may increase the risk of a major birth defect. Epoxide hydrolase deficiency may indicate susceptibility to fetal hydantoin syndrome. Figure 9-3 Facial features of the fetal hydantoin syndrome. Note broad, flat nasal ridge, epicanthic folds, mild hypertelorism, and wide mouth with prominent upper lip. (Courtesy of Dr. Thaddeus Kelly, Charlottesville, VA.) Figure 9-4 Hypoplasia of toenails and distal phalanges. (From Hanson JWM: Fetal hydantoin syndrome. Teratology 13:186, 1976, with permission.) In a follow-up study of long-term effects of antenatal exposure to phenobarbital and carbamazepine, anomalies were not related to specific maternal medication exposure. There were no neurologic or behavioral differences between the two groups.[23] However, children exposed in utero to phenytoin scored 10 points lower on IQ tests than children exposed to carbamazepine or nonexposed controls.[24] Also, prenatal exposure to phenobarbitol decreased verbal IQ scores in adult men.[25] Newer Antiepileptic Drugs Lamotrigine (Lamictal) has been studied in a registry established by the manufacturer, Glaxo Wellcome. Eight of 123 infants (6.5 percent; 95 percent confidence interval [CI] 3.1 to 12.8 percent) born to women treated with lamotrigine during the first trimester and followed prospectively to birth were found to have congenital anomalies. All of the mothers of children with malformations had a seizure disorder and some took at least one other medication during the pregnancy. Lamotrigine is an inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase and decreases embryonic folate levels in experimental animals, so it is theoretically possible that this drug would be associated with an increased malformation risk like the other antiepileptic drugs. The limited human data to date do not appear to indicate a major risk for congenital malformations or fetal loss following first-trimester exposure to lamotrigine. There are no epidemiologic studies of congenital anomalies among children born to women treated with felbamate, gabapentin, oxcarbazepine, tiagabine, topiramate, or vigabatrin. Some women may have taken anticonvulsant drugs for a long period without reevaluation of the need for continuation of the drugs. For patients with idiopathic epilepsy who have been seizure free for 2 years and who have a normal electroencephalogram (EEG), it may be safe to attempt a trial of withdrawal of the drug before pregnancy. Most authorities agree that the benefits of anticonvulsant therapy during pregnancy outweigh the risks of discontinuation of the drug if the patient is first seen during pregnancy. The blood level of drug should be monitored to ensure a therapeutic level but minimize the dosage. If the patient has not been taking her drug regularly, a low blood level may demonstrate her lack of compliance and she may not need the drug. Because the albumin concentration falls in pregnancy, the total amount of phenytoin measured is decreased, as it is highly protein bound. However, the level of free phenytoin, which is the pharmacologically active portion, is unchanged. Neonatologists need to be notified when a patient is on anticonvulsants, because this therapy can affect vitamin K-dependent clotting factors in the newborn. Vitamin K supplementation at 10 mg daily for these mothers has been recommended for the last month of pregnancy. Ref : Gabbe: Obstetrics - Normal and Problem Pregnancies, 4th ed., Copyright © 2002 Churchill Livingstone, Inc.