Buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare) - Arizona

advertisement

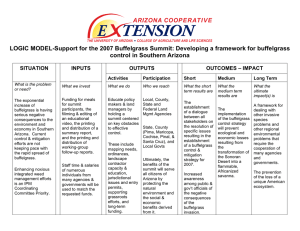

3 Invasive Species in the Sonoran Desert Region 11 INVASIVE SPECIES IN THE SONORAN DESERT REGION Invasive species are altering the ecosystems of the Sonoran Desert Region. Native plants have been displaced resulting in radically different habitats and food for wildlife. Species like red brome and buffelgrass have become dense enough in many areas to carry fire in the late spring and early summer. Sonoran Desert plants such as saguaros, palo verdes and many others are not fireadapted and do not survive these fires. The number of non-native species tends to be lowest in natural areas of the Sonoran Desert and highest in the most disturbed and degraded habitats. However, species that are unusually aggressive and well adapted do invade natural areas. In the mid 1900’s, there were approximately 146 non-native plant species (5.7% of the total flora) in the Sonoran Desert. Now non-natives comprise nearly 10% of the Sonoran Desert flora overall. In highly disturbed areas, the majority of species are frequently non-native invasives. These numbers continue to increase. It is crucial that we monitor, control, and eradicate invasive species that are already here. We must also consider the various vectors of dispersal for invasive species that have not yet arrived in Arizona, but are likely to be here in the near future. Early detection and reporting is vital to prevent the spread of existing invasives and keep other invasives from arriving and establishing. This is the premise of the INVADERS of the Sonoran Desert Region program at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. We have chosen nine invasive species to initiate the INVADERS program. Seven of these species are invasive plants and two are animal species. The two animal species are not yet in Arizona, but their arrival could be devastating to our state. The nine species are: Buffelgrass -Pennisetum ciliare Fountaingrass - Pennisetum setaceum Natalgrass - Melinis repens Sahara mustard - Brassica tournefortii Tamarisk (saltcedar) - Tamarix chinensis Athel tree - Tamarix aphylla Onionweed – Asphodelus fistulosus Red imported fire ant - Solenopsis invicta Argentine cactus moth - Cactoblastis cactorum Information on each of these species including their identification, impact, history, and distribution are included in the following pages of this handbook. This information is also available on the ASDM website at www.desertmuseum.org/invaders. 12 Buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare) What is it? Buffelgrass is a shrubby grass to 1.5 feet tall and 3 feet wide. It looks like a bunchgrass when small (either a seedling or recently burned, grazed, or cut). Older plants branch profusely and densely at nodes, giving mature plants a messy appearance. These nodal branches produce new leaves and flower spikes very quickly after light rains, making buffelgrass an extremely prolific seed producer. Some native grasses such as Arizona cottontop (Digitaria californica) branch sparsely and do not appear shrubby. Bush muhly (Muhlenbergia porteri) is a true denselybranched shrub; it differs from buffelgrass in its very delicate texture. An entire mature plant. A single basal stem teased out, showing the profuse branching above ground. Inflorescences are 1.5 to 5 inches long, fat brown to purplish when fresh or occasionally straw-colored. The spikes are crowded with dense bristly fruit which are actually burs without hardened spines. (For this reason buffelgrass is sometimes included in the genus Cenchrus, the burgrasses.) This is primarily a warm-season grass, but below 3000 feet in our region it can grow and flower after almost any rain. 13 The individual units visible in these buffelgrass inflorescences are basically soft burs. The most similar native grass is plains bristlegrass (Setaria macrostachya). The individual seeds are clearly visible. Why is it a Threat? Buffelgrass grows densely and crowds out native plants of similar size. Competition for water can weaken and kill larger desert plants. Dense roots and ground shading prevent germination of seeds. It appears that buffelgrass can kill most native plants by these means alone. Tumamoc Hill in Tucson, home of the University of Arizona's historic Desert Laboratory visible at left, has been overrun by buffelgrass in the last two decades. It has not burned, but native plants are declining and dying from lack of water. Photos: Travis Bean [Red brome (Bromus rubens) is another invasive grass that has covered huge areas of lower bajadas in the upper Sonoran Desert. This annual grass has caused serious damage in the past several decades. It grows densely only in wetter years and produces relatively mild fires, so fires are infrequent and don't completely kill native 14 communities in one episode. Nonetheless conversion is progressing where it has invaded.] Buffelgrass is a very drought-tolerant perennial, so it can remain dense and even spread in dry years. It is present to burn year round and supports hotter fires than those of red brome. The Sonoran Desert evolved without fire as an ecological factor and most of its plants cannot tolerate it. A single buffelgrass fire kills nearly all native plants in its path. The buffelgrass invasion is now destroying steep hillsides compared to red brome's flatter terrain, and is rapidly converting formerly rich biological communities into monocultural wastelands. A "natural" roadside with native vegetation. AZ Hwy 85 in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, where buffelgrass is controlled. Buffelgrass resprouts vigorously after fires, but most native desert plants are killed. Near Caborca, Sonora. The shoulders of this road near Saric, Sonora are almost 100% buffelgrass, a common result where it isn't controlled. Buffelgrass is abundant in the adjacent hills, but heavy grazing keeps it from reaching burnable density. This hillside near Caborca, Sonora recently burned, killing nearly all of the native plants. Only charred skeletons of teddy bear cholla (Cylindropuntia bigelovii) and a palo verde (Parkinsonia microphylla) are visible. The rich Arizona Upland vegetation that once grew here can be seen in the distance. There is growing evidence that buffelgrass depletes soil fertility in a decade or so. It then dies and leaves behind a sterile wasteland. No one knows how much time will be needed to restore such ruined land. 15 Distribution Native to the Old World where it is widespread in Africa, the Middle East, Indonesia and nearby islands, and tropical Asia. Introduced to Australia and the New World. In the Sonoran Desert Region buffelgrass is common in southern Arizona and most of Sonora. Habitat There are two seemingly unrelated habitats in the Sonoran Desert. In valleys and lower slopes buffelgrass invades disturbed areas such as roadsides and cleared or grazed fields. It Arizona it is spreading very rapidly along medians and shoulders of major highways and more slowly on smaller roads. In northern Sonora it has been present longer, and it dominates long stretches of smaller highways. From the town of Imuris, Sonora buffelgrass extends in a continuous ribbon along highway 15 all the way to Sinaloa, interrupted only by a few cities. A typical roadside habitat for buffelgrass (under the stopsign). The larger grasses are the related fountaingrass (Pennisetum setaceum), which is also a serious invasive threat. This cleared field is nearly pure buffelgrass. It has not dominated the surrounding flats which have not been cleared of vegetation. Its other habitat is steep rocky hillsides, mostly east- and south-facing slopes. It is most abundant on debris cones near the angle of repose. These steepest slopes may be the best establishment sites from which it will eventually spread. Some less steep hillsides are completely covered with buffelgrass, so the invasion may still be in its early stages. It occurs from near sea level to 4150 feet elevation. 16 Buffelgrass being censused on a hillside near Magdalena, Sonora. Most of the herbaceous plants have disappeared. A steep rocky hillside in the Pan Quemado Mts, Ironwood Forest National Monument. Several patches of buffelgrass are visible. History Buffelgrass was introduced to the United States about in the1930s as livestock forage. It was in planting trials at the Soil Conservation Service nursery in Tucson from 1938 to 1952. Several experimental plantings were done beginning in 1941 at Aguila near Phoenix. Most did not do well. (Another planting in Avra Valley west of Tucson in the early 1980s also died out where it was planted on flat ground.) Records of collections in natural habitat were sparse until about 1980 when it began a rapid expansion. One example is Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, where buffelgrass was rare before 1984 (Felger 1990). By 1994 it had occupied 20-25 square miles and was expanding rapidly. Few people other than botanists noticed it in Arizona before 1990. Today it is difficult not to see it in the southern half of the state. A survey of roads done by the Desert Museum in 2004 revealed the full extent of the buffelgrass invasion of Arizona and northern Sonora (map below). 17 Buffelgrass distribution along roads in Arizona and northern Sonora. Red symbols in both maps denote areas where buffelgrass is the dominant plant and dense enough to burn. Buffelgrass distribution in the Tucson vicinity. The survey was not completed within the urbanized zone; buffelgrass is present here in nearly every vacant lot and unpaved road shoulder. What can be Done? Buffelgrass can be controlled by manual pulling and herbicides. Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument nearly eradicated patches covering ca. 25 square miles in three years of intensive manual labor. After the initial control only minor efforts have been required to destroy new infestations (though searching the huge park takes a great deal of time). Volunteer groups such as Sonoran Desert Weedwackers are active in controlling it in other areas such as Tucson Mountains Pima County Park. The highest priority should probably be to control buffelgrass on roads outside of urban zones, because these are the seed sources for invasion of natural habitats. Second priority should go to the most valuable habitats such as parks. In the long run we may need biological control. This will be a controversial issue because buffelgrass is still valued as livestock forage. To this issue, it must be publicized that buffelgrass is not nearly as economically viable as first thought. Research in Africa, Australia, South America, Texas, and Sonora reveal that the average useful life of a buffelgrass pasture is only 10-12 years. Under exceptional management productive pastures have lasted only 15 or 16 years (Ibarra 1999). Buffelgrass impoverishes the soil and evenually dies, leaving behind a sterile wasteland that requires expensive efforts to restore productivity. The public and land management agencies must be educated to recognize Buffelgrass for the threat that it is. The state of Arizona declared it to be a noxious weed in March 2005. On the other hand, at least one branch of the federal government is breeding buffelgrass to develop more cold-hardy varieties. Other common names: African foxtail grass, anjan grass, syn. Cenchrus ciliaris. 18 References Tellman, Barbara (ed.). 2002. Invasive Exotic Species in the Sonoran Desert Region. University of Arizona Press. Ibarra F., Fernando. 1999. Lo mejor del dia del ganadero. Summary of oral presentation on website. 19 Fountaingrass (Pennisetum setaceum) What is it? Fountaingrass is an attractive, robust clumping grass that grows up to 3 ft tall and wide. Its long, wiry leaves are 11 to 30 in long from the base and form dense, light green clumps in summer. Together the old whitish and the new purplish inflorescences form a halo above the green leafy core. The cylindrical inflorescences are thick, 4 to 14 in long, round in cross-section, pink, or purplish during colder weather, and dry white. Soft silky hairs to over an inch long surround the fruits. This grass is most vigorous in the warm season (July-September), but also flowers most of the year below 3000 feet in our region. It appears to be somewhat more cold tolerant than buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare) as it reaches 4800 feet elevation in the Santa Catalina Mountains (650 feet higher than buffelgrass). Photo: Mark Dimmitt Buffelgrass is another introduced African grass in the genus Pennisetum, which is also a serious invasive species in the Sonoran Desert Region. It differs from fountaingrass in its smaller size (1 to 1.5 ft tall), branched stems, broad leaves and shorter (1.5 to 5 in long) fat, brown to purplish cylindrical inflorescences growing from nodes along the stems. Above 4000 feet, bullgrass (Muhlenbergia emersleyi) is a 3 ft tall, clumping native species that resembles fountaingrass. Its numerous small seeds with long (0.5 in) purplish bristles form loose, flattened, nodding banners that are unlike the cylindrical inflorescences of fountaingrass. Photos: Mark Dimmitt 20 Why is it a Threat? Fountaingrass is a large grass that produces lots of seeds that can spread rapidly spreads from cultivation into nearby disturbed areas, and eventually into natural habitats. It often forms dense stands and aggressively competes with native species, especially perennial grasses and seasonal annuals, for space, water, and nutrients. Fountaingrass provides lots of fuel, and is well adapted to fire. In Hawaii , fountaingrass fires are a serious threat to the native species. After burns, it regrows rapidly from extensive roots. In contrast, fire is not an ecological process in the Sonoran Desert or tropical communities to the south, and native trees, shrubs, and succulents are decimated by fire. In the Arizona Upland, grasses often dominate roadsides and fires are more frequent than in undisturbed habitats. Grasses that commonly occur with fountaingrass on roadsides include the native cane beardgrass (Bothriochloa barbinodis), plains bristlegrass (Setaria macrostachya), purple threeawn (Aristida purpurea) , spike pappusgrass (Pappophorum vaginatum), tanglehead (Heteropogon contortus) , the non-native barley (Hordeum murinum) , Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon) , Lehmann lovegrass (Eragrostis lehmanniana), Natalgrass (Melinis repens), red brome (Bromus rubens), and wild oats (Avena fatua). Threats from fountaingrass fires are most serious in natural riparian habitats in scenic mountain canyons. In the Tucson area, it has invaded the rocky canyons in Finger Rock, Pima, Sabino, and other Canyons in the Santa Catalina Mountains and King Canyon in the Tucson Mountains . Fountaingrass is less of a threat in desert grassland or chaparral above 3500 feet where fire is a natural process. It has been declared as a state noxious weed by Hawaii and Nevada . Distribution Fountaingrass is native to North Africa and the Middle East . It has been widely cultivated as an ornamental around the world and often escapes into natural habitats. In the United States, it is common in southern Arizona, southern California, southern Nevada, southwestern Utah, and Hawaii . It has also been found in Florida, Louisiana, Tennessee, Oregon, Colorado, and Texas . In Arizona it is widespread in the Phoenix, Tucson, Ajo, and Gila Bend areas in Maricopa and Pima counties. It is also common along the Colorado River from Lake Mead to Parker in Mohave and La Paz counties. A few plants have been found in Cochise, Gila, Pinal, Santa Cruz , and Yavapai counties. In the Mexican portion of the Sonoran Desert Region, it is only beginning to escape cultivation in Alamos, Kino Bay, and Magdalena (Sonora), near Ensenada (Baja California), and Mulegé (Baja California Sur). 21 Habitat Fountaingrass mostly occurs on disturbed roadsides, rocky outcrops, canyons, and cliffs from 2000 to 3500 feet in the Sonoran Desert Region in Arizona . It is most common in riparian habitats within paloverde-saguaro desertscrub in the Arizona Upland Sonoran Desert . It is less common in the Lower Colorado River Valley desertscrub down to about 985 feet, and in chaparral, desert grassland, and oak woodland up to 4800 feet. On the Fountaingrass invading a suburban north side of Tucson, it replaces roadside. Photo: Mark Dimmitt buffelgrass on roadsides and rocky road cuts. It is also common in another riparian habitat on flood lines and rocky shores of reservoirs and rivers in low-elevation (400 to 1200 feet) Mohave and Sonoran desertscrub. It is common from Lake Mead to Parker along the Colorado River in some very hot, dry areas. History Although fountaingrass was reported in Hawaii as early as 1914, it was first collected on roadsides in Arizona in the Santa Catalina Mountains (4500 ft elevation) and in Ajo in 1940. It was used in urban landscapes in Tucson as early as 1940, and cultivated in the Soil Conservation Nursery (now National Resource Conservation Service) in 1941. It was well established in the Santa Catalina Mountains by the 1940's and the Phoenix area by 1962. Later specimens were collected in nowprotected natural areas in the Tucson area including Tumamoc Hill (1968), the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum (1966), and King Canyon (1988) in the Tucson Mountains, and Sabino Canyon (1974) in the Santa Catalina Mountains. Like buffelgrass, it has expanded dramatically in many areas since 1990. What can be Done? Poorly-maintained nurseries can be sources of new invasive weeds. Fountaingrass in this nursery is in seed and can soon invade surrounding land. Fountaingrass can be controlled by physically removing the entire plant, including the seed-bearing inflorescences. Seedlings and small plants can easily be pulled by hand. Iron digging bars or shovels will help extract larger plants. It may be necessary to return to controlled areas for several years to remove seedlings. Chemical treatments with systemic herbicides may be needed to control large infestations. Herbicides have been sprayed from boats to control fountaingrass along rocky shorelines of Colorado River reservoirs. There are alternatives for fountaingrass in urban landscapes. Bronzeleaf fountaingrass (var. cupreum) is a 22 genetically-modified sterile cultivar that can be planted instead of the normal plants. Native grasses that resemble fountaingrass but are not invasive include bullgrass and deergrass (Muhlenbergia rigens). Beargrass (Nolina microcarpa) and desert spoon (or sotol, Dasylirion wheeleri) are native succulents that grow in large clumps that are attractive in desert gardens and road medians. Links California Exotic Pest Plant Council: http://ucce.ucdavis.edu/files/filelibrary/5319/17411.pdf Pima County Exotic Species Council: www.co.pima.az.us/cmo/sdcp/ National Resource Conservation Service, National Plant Data Center , USDA. 2004. The PLANTS Database, Version 3.5: http://plants.usda.gov/cgi_bin/plant_profile.cgi?symbol=PESE3 Plant Conservation Alliance, Alien Plant Working Group: www.nps.gov/plants/alien/fact/pesel.htm References Tellman, Barbara (ed.) 2002. Invasive Exotic Species in the Sonoran Desert . University of Arizona Press. 23 Natalgrass (Melinis repens) What is it? Natalgrass (synonym Rhynchelytrum roseum) is an erect grass to 28 in tall that has attractive long reddish or pink silky hairs on the triangular fruit at maturity, fading to silvery white with age. In the northern part of its geographic range, it is short-lived perennial or annual, but becomes stouter in warmer areas to the south. The branched inflorescences are open (2-3 in wide) and fluffy. The leaves are narrow and flat (3-8 in long) from unbranched stems. It can flower throughout the year under favorable temperature and moisture conditions but is limited by hard freezes. Photo: T.R. Van Devender Photo: Mark Dimmitt Bush muhly (Muhlenbergia porter) is a native species with pink inflorescences but differs from Natalgrass in its sprawling growth habit and tiny pink seeds in nebulous clusters growing from stem nodes. Arizona cottontop (Digitaria californica) also has white silvery hairs but the fruit are flattened, oval, and in slender spikes rather than open panicles. Why is it a Threat? In most areas in the Tucson vicinity, Natalgrass mainly occurs on roadsides and does not present a serious threat to natural ecosystems. But in eastern and north-central Sonora it left the roadsides and invaded natural grassland habitats beginning about 1990. As with Lehmann lovegrass (Eragrostis lehmanniana), weeping lovegrass (E. curvula), King Ranch bluestem (Bothriochloa ischaemum), and other non-native forage grasses in Arizona, the introduction of Natalgrass has recently taken over this Natalgrass results in changes in the hillside near Yécora, Sonora. Photo: T.R. composition and structure of desert Van Devender grassland, but not conversion to desertscrub or some other type of vegetation. In contrast to buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare), it does not appear likely 24 to invade drier desert habitats in the Sonoran Desert Region in patches dense enough to burn and convert desertscrub to savanna-like grassland. In Hawaii and some areas on the Mexican Plateau north of Mexico City, recurrent fires in dense Natalgrass stands threaten natural vegetation and native species. It is listed as an alien pest species in Hawaii. South of Nogales, Sonora, dense Natalgrass stands along the highway right-of-way burns regularly. In one area, a fire spread up a grassland slope and burned hop bush (Dodonaea viscosa) and other shrubs to the ground. It has colonized the canyon bottom and is invading the adjacent south-facing slopes of Pima Canyon in the Santa Catalina Mountains near Tucson. In the Mule Mountains five miles west of Bisbee in southeastern Arizona, it grows densely with velvet mesquite (Prosopis velutina) Natalgrass fire in highway median, south and ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens) in of Nogales, Sonora. Photo: T.R. Van desert grassland on a south-facing slope Devender very similar to those south of Nogales. It is intolerant of cold and dies back to the base at the first frost. Cold temperatures probably prevent it from expanding into many higher or more northern areas in Arizona. However, its behavior in warmer areas to the south suggests that it is prudent to watch it in the southern Arizona borderlands where many tropical plants and animals reach their northern distributional limits. Distribution Natalgrass is native to South Africa but is now introduced in the warmer parts of the world, including tropical Latin America in North and South America. In the United States it is mostly found in Florida, west along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico to south Texas, southern Arizona, and Hawaii. It also occurs in Maryland, Virginia, New Mexico, southern California, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. In Sonora, zacate rosado is common in the Nogales-Imuris area (north-central) and from Tepoca to the Yécora-Maycoba area (eastern). It is locally present in Sonoran Desert in central and west-central Sonora, and southward and eastward into more tropical areas. In Arizona Natalgrass is locally common in Pima County in the Santa Catalina and Tucson Mountains, and Tucson, and in Cochise County in the Mule Mountains west of Bisbee. It is uncommon in Santa Cruz County in the Santa Rita Mountains. Habitat Natalgrass is most common in Arizona on disturbed roadsides along paved highways in desert grassland 3000 to 4000 feet. In eastern and northern Sonora, and in the Mule Mountains west of Bisbee, it has spread into natural desert grassland. It is less common in the Arizona Upland Sonoran Desert down to 2400 feet and oak woodland up to 5700 feet. In Sonora, it is common in desert grassland northeast of Imuris and south of Nogales (to 4300 feet), and near Maycoba in the Sierra Madre Occidental in eastern Sonora (to 5400 feet). It occurs in desertscrub, foothills thornscrub, and tropical deciduous 25 forest from near sea level in the Guaymas area through the transition into oak woodland (3600 feet) above Tepoca in eastern Sonora. History This attractive grass with its long purplish-pink, silky hairs on the fruit and open inflorescences has been grown as an ornamental. It was grown for forage in the southeastern United States. In the Arizona Flora published in 1951, Natalgrass was only reported in Pima County in the Santa Catalina Mountains near Tucson. Since that time it has spread into many areas in the Tucson area and appears to be expanding its range in the Arizona-Sonora borderlands. What can be Done? Management and control methods are not well known. It should not be planted as an ornamental and should be pulled by hand in areas of conservation concern. Other Common Names: rose Natalgrass, Natal redtop, zacate rosado, espiga colorada, pink feathergrass, rubygrass, Holme's grass, blanketgrass. Links Utah State University Intermountain Herbarium Grass Manual (distribution map in the United States) USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Plants Profile Fact sheet on Natalgrass in the Pacific Islands References Gould, F. W. 1977. Grasses of the Southwestern United States. University of Arizona Press, Tucson. 26 Sahara mustard (Brassica tournefortii) What is it? Numerous Old World mustards have invaded North America. Of these Sahara mustard (aka several other names) is the newest and by far the worst. It is a robust, fast-growing, drought-tolerant winter annual that prefers sandy soils. The basal rosette of divided hairy leaves can span three feet in wet years. The nearly leafless flowering stems branch profusely and grow to a height of about two feet, creating the appearance of a shrub from a distance. The small light yellow flowers are selfpollinating, so each of the thousands of them sets a seed pod. Large plants produce up to 9000 seeds. Dried plants break off at the base and tumble like Russian thistle (tumbleweed, Salsola tragus), spreading seeds rapidly across the landscape. When wet, the seeds are sticky with mucilage and can be transported long distances by animals and perhaps vehicles. All photos: Mark Dimmitt Several other exotic mustards are also invasive threats to the Sonoran Desert. Most of them have been here a long time and have already invaded most suitable habitat; we can hope they will not cause further damage to communities. Black mustard (Brassica nigra and similar spp.) can also grow to nearly three feet tall. It is distinguished from Sahara mustard by its smaller leaves and larger, bright yellow flowers. London rocket (Sisymbrium irio) is a major pest in gardens as well as roadsides and undisturbed desert areas. It has bright shiny leaves and flower stalks up to 2 feet tall with small bright yellow flowers. 27 Arugula (aka rocket salad, Eruca vesicaria sativa) is a culinary herb with one-inch whitish to yellowish fragrant flowers. The plants can grow to 5 feet tall in wet years as in the image at right. It is now the dominant plant in much of the area along Interstate 8 from Gila Bend west to the Maricopa County line, a distance of 45 miles. Along this stretch it extends on both sides of the freeway as far as the eye can see. It has been there for many decades and is apparently spreading slowly. Because of the stealthy spread and its remote location, its invasion has gone largely unnoticed except by botanists. Though a significant local threat, arugula is a minor problem compared to Sahara mustard. Almost everything visible in this scene is arugula. The plants are nearly as tall as the widely-scattered creosotebushes barely visible in this scene taken in March 2005. Why is it a Threat? This dune evening primrose seedling (Oenothera deltoidea, right) will soon be overgrown by the Sahara mustard seedlings next to it. Sand verbena (Abronia villosa) struggling to survive beneath a large Sahara mustard that germinated at the same time. This weed grows very fast, smothering native herbaceous plants and even competing with shrubs for light and soil moisture. The famous wildflower fields of the sandy valleys of Lower Colorado River Valley Sonoran Desertscrub are in danger. In the winter-spring of 2005 about three-quarters of the prime display areas were overrun with Sahara mustard in California and Arizona. Fortunately it does not do well in every year. It is known that a freeze can kill the plants and give native flowers a chance to grow and reproduce. However, freezes are uncommon in the low desert. 28 Now: 2005 Then: 1998 What we have lost: These two scenes were both photographed in the northern end of the Mohawk Dunes in western Arizona. In 2005 Sahara mustard covered 70-90% of the surface area at this location. Almost no native wildflowers bloomed here in 2005. In wet years Sahara mustard covers the ground almost 100% and can carry fire when it dries. It is a frightful thought that hyperarid desert, including sand dunes, can burn because of this weed. There have already been documented fires in the dunes west of Blythe, CA and the Pinta sands in the Cabeza Prieta Wildlife Refuge. This latter site is a remote, uninhabited, and previously pristine habitat. Most Sonoran Desert plants cannot tolerate fire; burned areas become wastelands of nearly pure Sahara mustard. Snow Creek Canyon on the south side of the San Jacinto Mountains near Palm Springs, CA used to be covered in huge carpets of pink, yellow, and white flowers in wet springs. Now it is almost 100% Sahara mustard. This area of sand dunes in the Chuckwalla Valley, CA (west of Blythe) burned, killing most of the creosotebushes. Sahara mustard was the fuel. This is the worst invasive plant in the Sonoran Desert in terms of area covered and damage inflicted on the biotic community. In riparian communities saltcedar is its rival. Distribution 29 Sahara mustard is abundant in the Desert Southwest at low and mid elevations from southeastern California to southern Nevada and south into Baja California and Sonora. It's rare in southern New Mexico and western Texas. It extends to the edge of the tropics in Mexico. It is native to many areas of the Old World from north Africa and the Middle East east to southern Europe and Pakistan. Habitat It is most abundant in Lower Colorado River Valley Sonoran Desertscrub and lower Mohave Desertscrub. It's currently uncommon in Arizona Upland Sonoran Desertscrub, and rare in chaparral and desert grassland. It favors sandy, disturbed soils at low elevations, but its range is expanding rapidly into undisturbed soils including rocky hillsides in Arizona Upland. The literature lists its elevational range as 250 to 2800 feet, but it has recently been found above 4100 feet. One way that weeds invade new habitats: This huge field of dried Sahara mustard This mound of imported soil in Tucson, AZ near very arid Parker, AZ was several was infested with seeds of Sahara miles long. If it catches fire, the houses in mustard and London rocket. the background are at risk as well as the few native plants left. History This recent invader probably arrived in North America as a contaminant in crop seed. The first record is from California's Coachella Valley in 1927. It was first discovered in Arizona-Sonora in 1957 on Mexico Highway 2 near Yuma. By the 1970s it was widespread in the low desert in Arizona, California, Baja California, and Sonora. It doesn't seem to have caused much alarm until the early 1990s when people began to realize how much habitat it was overrunning. Sahara mustard was first collected in Tucson in 1978, and in 1991 was reported as rare. Today it is widespread and locally common in the metropolitan area and surrounding suburbs. What can be Done? In small areas Sahara mustard can be eradicated by pulling plants before they mature seed. This is most effective in new invasions where a seed bank has not been established. 30 Control in the thousands of square miles of remote desert habitat seems almost hopeless. It is unlikely that a biological agent, if found, would be approved because many important crop plants are in the genus Brassica (e.g., cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, brussels sprouts). There are also numerous native mustards that might be threatened by a biological agent. In selected areas herbicide treatment may be effective. Sahara mustard tends to be the first annual to germinate after a rain, so early treatment may reduce its abundance and allow later-germinating natives to establish. The spread of Sahara mustard can be reduced by controlling it along roads, which provide corridors for rapid invasion into new habitats. Other Common Names: Asian mustard, Moroccan mustard, desert mustard, southwestern mustard, Mediterranean mustard, Mediterranean turnip, wild turnip, prickly turnip, turnip weed. References Felger, R.S. 1990. Non-native plants of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Tech. Rep. 31. Tucson: Cooperative National Park Research Studies Unit. Felger, R.S. 2000. Flora of the Gran Desierto and Rio Colorado of Northwestern Mexico. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. Minnich, R.A. and A.C. Sanders. 2000. Brassica tournefortii Gouan. In: Bossard, C.C., J.M. Randall, and M.C. Hoshovsky. eds. Invasive Plants of California's Wildlands. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles. 360 pp. Tellman, Barbara (ed.). 2002. Invasive Exotic Species in the Sonoran Desert Region. University of Arizona Press. Van Devender, T.R., R.S. Felger, and A. Burquez M. 1997. Exotic Plants in the Sonoran Desert region. 1997 Symposium Proceedings, California Exotic Pest Plant Council. Website 31 Tamarisk, saltcedar, athel tree (Tamarix spp.) What is it? Tamarisk is a general term for several species of Old World shrubs and trees in the genus Tamarix with scalelike leaves on very thin terminal twigs. Saltcedars are large shrubs or small trees 8-16 feet tall and usually less wide. They have tiny, triangular, scale-like leaves that are winter-deciduous. The flowers are pink to near-white, densely crowded along branched terminal spikes; they appear from January to October. Fruit and seeds are tiny, brown, inconspicuous. The several species introduced to North America have been labeled Tamarix chinensis (our current choice for southern Arizona plants), T. ramosissima, T. pentandra, T. parviflora, and T. gallica. They are very similar in appearance and are hybridizing, so distinguishing among them is difficult. Apparently the hybrid populations are the most invasive. Young saltcedar (Tamarix cf. chinensis) in flower. Photo: Steve Dewey, Utah State University; www.forestryimages.org Tamarix chinensis branch with flowers. The tiny triangular leaves stick out from the stems, giving the twigs a prickly feel. Photo: T.R. Van Devender Athel tree (Tamarix aphylla, also called saltcedar) is a large evergreen tree to 50 feet tall and wide with virtually no leaves (reduced to tiny scales) and inconspicuous whitish flowers. It was long thought to be sterile and therefore at most mildly invasive, but it is reproducing from seed in some localities. It has been doing so at Lake Mead for 30 years, and is hybridizing with the deciduous saltcedars. 32 A young-mature athel tree at Lake Mead. Photo: Elizabeth Powell Closeup of athel tree twigs showing the tiny scalelike leaves and small white flowers. Photo: Mark Dimmitt; inset: Elizabeth Powell Australian pines (Casuarina spp.) could be confused with tamarisks. They have similar thin branches and scale-like leaves. Casuarinas don't seem to be invasive in the southwestern U.S., where they are found mostly in landscaped areas. Why is it a Threat? Tamarisks are extremely invasive in riparian communities, often nearly completely replacing native vegetation with impenetrable thickets. They are extremely competitive against native vegetation because they are aggressive usurpers of water. They also sequester salt in their foliage, and where flooding does not flush out soil salts the leaf litter increases the salinity of soil surfaces. Dense stands of saltcedars support lower biodiversity than the natural communities they displace. This stretch of Tonto Creek above Roosevelt Lake in Arizona is choked with Tamarix chinensis. Most of the green on the valley floor is this saltdecar. Photo: Mark Dimmitt Several miles of Greene Wash south of Casa Grande, AZ is dominated by athel trees. These may have propagated by pieces of branches that wash downstream in floods and take root, or they may be seeding. Natural washes in this region are vegetated by desert ironwood trees (Olneya tesota) and blue palo verde (Parkinsonia florida). Photo: Mark 33 Dimmitt Distribution Tamarisks are almost throughout the Southwest below about 6000 feet elevation. In Arizona they are widespread, especially south of the Mogollon Rim and in the Grand Canyon. Habitat Tamarisks occur mostly on low ground where water collects. They are most abundant in riparian habitats, both natural and artificial, often in extensive pure stands. They are less common in drier places. They thrive in alkaline and saline soils. History Various species of tamarisks were in cultivation in the United States in the early 1800s. The National Arboretum released T. pentandra in 1870. Tamarisk was first noticed to be escaping from cultivation in 1880, and by the end of the century it was common along southern Arizona and Texas rivers. What can be Done? There are teams of "tammywackers" in several states that are making progress in local areas. Specially modified jacks are used to grip and pull trees up by their roots. Cutting and treating the stumps with herbicides gives good control. Aerial spraying is being used in large areas where tamarisks have completely taken over. In areas too large or too remote for manual control, flood management can reduce the dominance of saltcedars. Periodic floods prevent saltcedars from forming dense thickets, permitting native trees and substory plants to establish and maintain codominance. References Gaskin, J.F. and P.B. Shafroth. 2005. Hybridization of Tamarix ramosissima and T. chinensis (saltcedars) with T. aphylla (athel) (Tamaricaceae) in the southwestern USA determined from DNA sequence data. Madroño 52(1):1-10. 34 Onionweed (Asphodelus fistulosus ) What is it? Onionweed is an herbaceous perennial in the lily family (Liliaceae) to about a foot tall and almost as wide. Clusters of long, tapering, round, hollow leaves very much resemble chives or scallions. Leaves sprout after winter rains. Flowers appear in spring. Plants die to the ground during dry season. The flat flowers are less than a half-inch across and have six petaloid parts, each white with pink center line. They are sparsely distributed on branched spikes to almost two feet tall. Fruits are 1/8-inch round capsules. Mature plant in flower. Photo: Mark Dimmitt Onionweed might be confused with some native onions (Allium spp.) Allium macropetalum (desert onion) is a much shorter plant with leaves rarely more than four inches tall. Taller native onions grow in different habitats than onionweed. Closeup of flower. Photo: Mark Dimmitt Dried plant with seed capsules. Photo: USDA Why is it a Threat? Onionweed is an aggressive invasive species. Introduced as an ornamental, it easily escapes cultivation into surrounding unirrigated land. It seeds prolifically and can establish large populations quickly. It is unpalatable to cattle and apparently to most wildlife, so it is very persistent once established. To date it tends to invade disturbed ground, so it is unclear whether it will be a threat to natural communities. 35 Distribution Native to southern Europe, Mediterranean Africa, and Western Asia. In the United States onionweed occurs in California (in several coastal southern counties), Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. Also known to be in Mexico. It is a noxious weed causing problems in Australia. Arizona infestations are primarily in the southeastern corner of the state. A few small infestations have been found in Tucson. Reported but unverified in Ajo. Habitat In the Sonoran Desert region this weed seems to do best in areas above the desert that receive moderate winter rainfall. A well-established population in suburban Tucson was reduced to only two plants after the severe drought of 2002. Plants have been found in Arizona from about 2000 feet elevation to at least 4500 feet. History Onionweed invading a roadside in Plants introduced into the United States in southeastern Arizona. Photo: USDA the 1980s may be the founders of our invasion. They were offered for sale in Alpine, Texas and Phoenix, Arizona as early as 1984. Some of the original US plants were collected from a naturalized population near Saltillo, Coahuila, Mexico, where the species was documented in 1930. What can be Done? Some nurseries offer onionweed as an ornamental even though it is a prohibited noxious weed in many states as well as a federally listed noxious weed. Do not buy it or plant it, and eradicate it if it is established on your property. Pulling the plant is usually not effective. The top breaks off leaving the tuberous roots underground. They must be dug up by the roots or sprayed with herbicide. A flowering plant in desert grassland with mesquite. Other common names: pink asphodel, hollow-stemmed asphodel Photo: USDA APHIS Archives, www.forestryimages.org 36 Links USDA Plant Database Profile InvasiveSpecies.org onionweed page The Nature Conservancy's Invasive Species Initiative References (The literature on this species is very sparse 37 .) Red Imported Fire Ant (Solenopsis invicta) What is it? The red imported fire ant (RIFA) is a small reddish brown ant from South America . There are six known species of fire ants (Solenopsis spp.) in the United States, three of which are found in Arizona. These three species are the southern fire ant (S. xyloni), and two species of desert fire ant (S. aurea and S. amblychila). RIFA has not established in Arizona, but is present in the bordering states of New Mexico and California. It was discovered near Yuma, Arizona but was exterminated. Adult red imported fire ants. Photo: USDA RIFA workers marked with wire bands. APHIS PPQ Archives, Photo: Bart Drees www.forestryimages.org . RIFA are small but highly aggressive. They inject a necrotising, alkaloid venom when they sting. The stings result in painful, itchy, and persistent pustules, and sometimes in severe allergic reactions. Five million people are stung each year in the southeastern United States. About 25,000 of these people require medical consultation. When a fire ant mound is disturbed, workers boil to the surface, run up any legs, arms, etc. in the vicinity, grab the victim's skin in their mandibles and sting synchronously in response to the slightest movement. The attacks are coordinated and dozens or even hundreds of workers sting in unison. Fire ants swarming boot after mound disturbance. Photo: Bart Drees. Pustules from RIFA stings. Photo: Murray S. Blum, The University of Georgia, www.forestryimages.org 38 Fire ants live in colonies that may have 100,000 to 500,000 ants. The queen of the colony can lay from 1500 to 5000 eggs per day, never leaves the nest and can live for many years. Worker ants take care of the queen and her eggs, build the nest, defend the colony, and find food. Preferred food of fire ants consists of protein-rich sources such as insects and seeds. Winged male and female ants fly from the colony in the spring and summer to mate in the air. The males die and the females become queens that start new colonies. Only the red imported fire ant has a median clypeal tooth and a striated mesepimeron; these may be difficult to see at first. RIFA also have an antennal scape that nearly reaches the vertex, a post-petiole that is constricted at the back half, and the petiolar process is small or absent. Of the native fire ant species, the southern fire ant (Solenopsis xyloni) looks the most like the red imported fire ant. It can be identified by its brown to black color, well-developed petiolar process, and no median clypeal tooth. Desert fire ants (Solenopsis aurea and S. amblychila) are both yellowish-red to reddish-yellow and have a well-developed petiolar process. RIFA can also be identified by the proportion of large to small workers in disturbed mounds. If half the workers in disturbed mounds are large and dark, it is RIFA. If only a few large ants appear relative to hundreds of small ants, it is non-RIFA. Side view of adult RIFA worker. Photo: USDA APHIS PPQ Archives, Median clypeal tooth can be seen here on www.forestryimages.org. head above the mandibles. Mandible has 4 teeth. Photo: Carl Olsen 39 Table: Characteristics of RIFA and RIFA mounds Characteristic Description RIFA # of node segments 2 # of sizes of workers Many (polymorphic) Size of workers 3 – 7 mm Shape of thorax Uneven # of antennal segments 10 with two-segment club at tip # pairs of spines in thorax None Color Reddish brown, abdomen darker Stinger Present, inflicts pain, leaves white pustule (pustule is not an allergic reaction) Mound Material Formed from excavated soil Size Wider than a dinner plate at its base Shape Amorphous, often oval shaped like a mountain cone Visibility Above ground, 4” to 24” tall Entrance None visible, ants access mound through subterranean tunnels that spoke out from the central mound Texture Has a fresh-tilled appearance, especially after a rain Size variation in RIFA worker ants and queen on the right. Photo: S. Porter. RIFA mounds have a fresh tilled appearance. Photo: Bart Drees. Why is it a Threat? RIFA colonies are extremely destructive. They dominate their home ranges due to their large numbers and aggressiveness. The lack of natural enemies results in population booms in areas they invade. 40 RIFA alter the composition of the ecological communities in the areas they invade. They outcompete and frequently eliminate native fire ants. They also compete with other animals for food and alter abundance of prey species. RIFA attack eggs and young of many bird and reptile species. In areas of high infestation, RIFA have significantly reduced northern bobwhite quail populations (Allen et al. 1995) and may completely eliminate ground-nesting species from a given area (Vinson and Sorenson 1986). They also attack small mammals such as rodents and have been known to attack and sometimes kill newborn deer and cattle. Due to a 10-20 year lapse before bird population reductions are observed, it is suggested that actual effects of RIFA on animal populations may be underestimated (Mount 1981). Natural plant ecosystems could potentially be impacted as well. RIFA predates upon solitary bees that are pollinators of certain plants (Vinson 1997) and move and feed on large quantities of seeds. Tricolor heron chick being attacked by fire RIFA feeding on plant nectar. Photo: S. B. ant workers. Photo: Bart Drees. Vinson. Stings from RIFA create health problems for many humans. Fire ants sting repeatedly and venom is injected from the poison sac with each sting. RIFA venom has a high concentration of toxins that cause an intense burning and itching that lasts for an hour and is followed by a blister that becomes a white pustule. Broken or scratched pustules can result in secondary bacterial infections and permanent scars. In some individuals, severe allergic reactions can occur resulting in anaphylactic shock and even death (Dowell et al. 1997). RIFA worker biting and stinging human. Photo: Texas Department of agriculture file photo. Secondary infection following RIFA sting on hand. Photo: Texas Department of Agriculture file photo. 41 RIFA cost the US billions of dollars a year in damage to agricultural crops and equipment, livestock, wildlife, public health, and electrical equipment such as air conditioners, traffic signal boxes, electrical and utility units, telephone junctions, airport landing lights, electric pumps for oil and water wells, computers, and even car electrical systems. Control methods for RIFA are extremely costly. Fire ant mound in electrical utility housing. Photo: S. B. Vinson. RIFA in traffic control relay switch box. Photo: Bart Drees. Distribution RIFA are native to South America and were brought to the US sometime around the 1930's. They now occupy more than 275 million acres of land in the US and are found in Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, South Carolina, North Carolina, Texas, Louisiana, Tennessee, New Mexico , Oklahoma, and California. They invade via transported nursery stock, honeybee colonies, and on empty trailers and trucks. Cold temperatures may limit the northward spread of RIFA in the US and the westward spread may be limited by drier conditions. Natural dispersal occurs on flowing water. Areas with seasonal flooding are vulnerable to RIFA invasion. RIFA colony floating in flood water. Photo: RIFA colony emerging from flood water. Bart Drees. Photo: Bart Drees. Habitat In infested areas, colonies are common in lawns, gardens, school yards, parks, roadsides, and golf courses. Nests generally occur in sunny, open areas and are most common in disturbed and irrigated soil. RIFA mounds are 4 to 24 inches tall and have no visible surface entrance. Mounds are accessed through subterranean tunnels 42 that spoke out from the central mound. Non-RIFA mounds rarely exceed an inch or 2 in height. RIFA mounds have a fresh-tilled appearance, especially after a rain. Typical RIFA mound. Photo: USDA APHIS PPQ Archives, www.forestryimages.org . Profile diagram of RIFA mound. Photo: Texas Cooperative Extension file photo. History RIFA are believed to have arrived in the southern United States around the 1930's on ships from South America as ballast waters were dumped or goods were unloaded. Their range expanded rapidly and today they occupy 13 US states and Puerto Rico . What can be Done? RIFA is a regulated species in Arizona. To keep RIFA out of Arizona, the Arizona Department of Agriculture has been conducting surveys at high-risk sites such as nurseries, parks, truck stops, etc. In 2004, all samples collected were negative for RIFA. The drier climate in Arizona is a limitation for this species, however, as we irrigate more lawns, agricultural fields, and golf courses, we increase our chances of a successful RIFA invasion. Once RIFA has established in an area, the chances of eradicating it are slim and control becomes the primary means of fighting its spread. It is vital that we prevent the spread of this species. RIFA very easily travel in potted plants and soil and in our vehicles. If RIFA is detected, citizens should contact the Arizona Department of Agriculture for confirmation and eradication. Eradication methods are complex due to the life cycle of the species and should be conducted by trained individuals. Links Arizona Department of Agriculture Red Imported Fire Ant Update Invasivespecies.gov – a gateway to Federal efforts concerning invasive species Texas Imported Fire Ant Research and Management Project University of Florida Red Imported Fire Ant Site US Department of Agriculture APHIS Imported Fire Ant Information 43 References Allen, CR, Lutz RS, and Demarais S. 1995. Red imported fire ant impacts on northern bobwhite populations. Ecological Applications 5(3):632-638. Dowell, RV, Gilbert, A, and Sorenson J. 1997. Red imported fire ant found in California . California Plant Pest and Disease Report 16(3-4) June-September: 50-55. Mount RH. 1981. The red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) as a possible serious predator on some southeastern vertebrates: direct observations and subjective impressions. Journal fo the Alabama Academy of Science 52:71-78. Vinson SB. 1997. Invasion of the Red Imported Fire Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Spread, Biology, and Impact. American Entomologist 43(1):23-29. Vinson SB, Sorenson, AA. 1986. Imported Fire Ants: Life History and Impact. The Texas Department of Agriculture. P.O. Box 12847 , Austin , Texas 78711 . 44 Argentine Cactus moth (Cactoblastis cactorum) The adult cactus moth is not distinctive; there are thousands of species of small brown moths. The egg sticks and larvae, however, are easy to recognize. Photo: Susan Ellis, USDA APHIS PPQ www.forestryimages.org Prickly pear pad hollowed out by larvae of the Argentine cactus moth. Photo: Les Tanner, Northwest Weeds, www.forestryimages.org What is it? The Argentine Cactus Moth (aka Cactoblastis cactus moth) is a small (22-35 mm) grayish-brown moth. The larvae are 25-30 mm in length and bright orangish-red with large dark spots that form cross bands. In Florida there can be three generations in a year. The eggs are laid in a series of up to 140 that creates a chain, looking like a stick or spine on the surface of the prickly pear pad (cladode). Upon hatching the larvae burrow into the pad and begin feeding gregariously on the tissues. This feeding consumes the cladode completely and the larvae move to other ones before pupation. The distinctive "egg stick". Photo: Susan Ellis, USDA APHIS PPQ www.forestryimages.org Larvae inside a prickly pear pad. Photo: Susan Ellis, USDA APHIS PPQ www.forestryimages.org Why is it a Threat? As a natural feeder on prickly pears (Opuntia species) the caterpillars of this moth are capable of destroying plants and populations of these plants. Prickly pear cacti are popular in residential and commercial landscapes throughout the southwest US and Mexico . Additionally there is widespread and valuable commercial and traditional use of the plants in Mexico. Opuntia production of food for humans and 45 livestock are the major uses. It is estimated between 2% of the value and production from agriculture in Mexico is from Opuntia. Top left: A field of prickly pears (Opuntia ficus-indica) being grown for nopales (edible pads) or tunas (edible fruits) near Hermosillo, Sonora. Top right and bottom left: Tunas for sale in Hermosillo market. Bottom right: Tunas prepared to eat. Photos: T.R. Van Devender Widespread invasion by this moth could lead to extensive destruction of natural Opuntia populations that serve as food for wildlife such as deer, javelina, rodents, and coyotes. Birds use prickly pears as nesting sites. Distribution The moth is native in the South American countries of Argentina , Brazil , Paraguay and Uruguay. It was introduced into Australia in 1926 as a control for the invasive spread of prickly pears that had been introduced as animal fodder. Introduction has occurred in African, Asian and island countries since then. 46 The arrival in Florida may have natural dispersion from the West Indies or on imported plants. Habitat Suitable habitat in the U.S. has not been determined. It can live on many species of prickly pears, but it is not known whether it can tolerate the arid climate of the Southwest. If Cactoblastis can invade the Sonoran Desert, prickly pears will virtually disappear from the landscape. Photo: Mark Dimmitt History The moth is native to several South American countries. It was discovered in the Florida Keys in 1989 and has now spread north to South Carolina and east into Alabama What can be Done? Monitoring Opuntia in nurseries and home landscapes in the path of expansion of the range of Cactoblastis for evidence of infestation will be critical for early detection. Research into control methods is being conducted, looking at chemical, biological and sterile insect techniques (SIT). Control by available insecticides may be appropriate in nursery and small landscape settings, but not in widespread landscapes or agriculture. Specific Biological Control agents (predators) have not been identified and study in the home range of the moth is continuing. Sterile Insect Techniques is a process of releasing sterile males into a population, they breed with fertile females resulting in sterile eggs, thus fewer offspring. Studies with this technique will take place in 2005. 47 The oozing wounds on this prickly pear pad are symptomatic of several species of cactus borers, not necessarily Cactoblastis. Photo: USDA This saguaro seedling is infested by the native blue cactus borer (Cactobrosis fernaldialis). The larva of this moth is bluish in color and do not feed in colonial groups. This native rarely causes lethal damage to larger cacti. Photo: Mark Dimmitt Links National Invasive Species Council " invasive species of the month" for March 2005 University of Florida Featured Creatures: the cactus moth European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) References Solis, M. Alma, Stephen D. Wright and Doria R. Gordon. 2004. Tracking the Cactus Moth Cactoblastis cactorum Berg.as it flies and eats its way westward in the US . News of the Lepidopterists' Society, Vol. 46 Number 1. Soberon, J., J. Golubov, and J. Sarukhan , 2001. The Importance of Opuntia in Mexico and Routes of Invasion and impact of Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Florida Entomologist 84 (4). 48