The Empirical Basis for Statutory Database Protection After the

advertisement

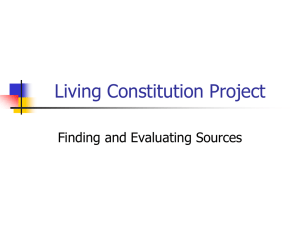

The Empirical Basis for Statutory Database Protection After the European Database Directive by Matt Block The debate: whether to increase protection for databases in the United States. In the debate over whether the U.S. should enact database protections similar to those in Europe, the rhetoric and philosophical arguments have been prominent and the facts themselves downplayed. A survey of the available evidence in 2002, for instance, noted that there was no good evidence yet adduced of many of the empirical factors in the debate.1 This is as ironic as it is understandable: it is the facts themselves that would receive protection under database legislation, but the facts themselves are difficult to find and track. Nonetheless, the facts are critical. Some scholars have noted that any policy change may create substantial unintended consequences. Thus, compelling empirical evidence should be required before dramatic policy changes are undertaken.2 Instead of such evidence, both proponents and opponents have argued using compelling economic theory. Proponents have argued that measures that benefit database producers also benefit the public at large; there is no conflict between the interests of the two groups.3 This is because an optimal output decision on the part of database producers will also be efficient. It will create sufficient incentives to produce new databases, but will allow consumers to purchase databases at a reasonable rate. However, they have argued, databases have characteristics of public goods, and must be treated differently as a result. In particular, databases have a declining marginal cost, because Justin Hughes, “Political Economies of Harmonization: Database Protection and Information Patents,” Cardozo Law School: Jacob Burns Institute for Advanced Legal Studies, Research Paper Series No. 47 (August 2002). Available at http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=318486. 2 See Hughes, supra note 1. 3 See Braunstein, infra. 1 1 the cost of reproduction or additional access is approximately zero. Thus, database producers need some mechanism to protect and recoup their initial investment in database production against second-comer free-riders. Opponents argue that the free-rider problem is overstated and easily solved with self-help and market mechanisms and existing legislative protection.4 They argue that databases are inputs into other productive activity, including further database production, so that any legislative remedy to the “free-rider” problem may ultimately lead to decreased database production and quality, and to lower productivity in other areas. Indeed, some opponents argue even more forcefully: because market economies depend on the free flow of information, increased protection may actually bind the invisible hand of market forces, and completely upset the existing incentive system.5 Thus, protectionist measures may not even have the limited incentive value the proponents suggest, and they will certainly increase the costs of developing (and therefore decrease the production of) derivative databases, which use existing databases as inputs. In addition to the economic arguments, commentators on both sides make moral and natural rights arguments for their positions. Proponents argue forcefully that anyone who invests in the creation of a thing has a natural right to recoup that investment. They argue that no one would ever advocate allowing purveyors of physical goods to simply repackage their competitor’s works, and that allowing “pirates” to “free-ride” on their creative efforts amounts to the same thing. Opponents argue that information is different See generally Stephen M. Maurer, “Raw Knowledge: Protecting Technical Databases for Science & Industry,” A Report for the National Research Council’s Workshop on Promoting Access to Scientific and Technical Data for the Public Interest, (January 1999). 5 See generally James Boyle, Chapter 4: Information Economics, Shamans, Software, and Spleens: Law and the Construction of the Information Society, pp. 35-46 (1996). 4 2 from property, that the normally cognized rights in information are entirely statutory and not natural, and that information “wants to be free”.6 Where is the evidence? As it happens, little empirical evidence has been produced on either side of the debate. Proponents of database protection argue that there is not enough database production today, and that increased protection will create incentives for new creation.7 Because there are other proposals, however, they also argue that increased protection is the best way to create these incentives.8 They argue that increased database production will be good for society.9 However, proponents have offered no evidence that these things are actually happening, or will actually happen. On the other side, opponents of increased protection argue that increased protection will disincent creators to compete on quality, create awkward new barriers to entry, and raise the costs of creation for second-comers.10 On the net, they argue, this may actually lead to less, and lower quality, database creation. Opponents too, however, have been silent as to significant examples of their dire predictions coming to pass. The reason for the silence of both opponents and proponents is the difficulty in obtaining the facts. For an overview of the arguments and other insights, see J.H. Reichman, Pamela Samuelson, “Intellectual Property Rights in Data?,” Vanderbilt Law Review Vol. 50, p. 51 (January 1997). 7 See Yale M. Braunstein, “Economic Impact of Database Protection in Developing Countries and Countries in Transition,” WIPO Standing Committee on Copyright and Related Rights, Geneva (April 4, 2002). 8 Id. 9 Id. 10 The critical difference may stem from opponents’ recognition of databases as an input to database production. Compare Jonathan Band, Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Courts and Intellectual Property of the United States House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary on the Collections of Information Antipiracy Act, H.R. 2652 (February 12, 1998) with Laura D’Andrea Tyson, Edward Sherry, Statutory Protection of Databases: Economic and Public Policy Issues, available at http://www.house.gov/judiciary/41118.htm. 6 3 As difficult as it may be to find and track, the evidence is available. Since 1998, Europe has been undertaking a natural experiment in incentives to create. By 2001, all of the EU countries had implemented, at least partially, the European Database Directive.11 The goal of the Directive was to harmonize protection for commercial databases, so that they could be made available throughout the EU, and thereby generate higher profits that would lead to greater incentives to create new databases. Because the databases sought to be protected were commercial in nature, they are likely to be advertised and listed in commercial directories. The Gale Directory of Online, Portable, and Internet Databases is published each year and tracks databases throughout the world that are made available publicly to commercial users to view and access electronically.12 Admissible databases are either available as a CD-ROM or on other media, or they are actually published online. There is an important caveat; the Directory lists only commercial databases, and is silent as to those made freely available.13 Thus, it lists a sample of the databases that are commercially available, easily susceptible to automated copying, and subject to protection under the American proposals and the European laws. 11 Different entities date the various implementations at different times, perhaps because implementations themselves have been somewhat piecemeal in their coverage. The NautaDutilh Final Report sets the final implementation date as being that of Luxembourg, which implemented the directive in 2001. 12 Gale Directory of Online, Portable, and Internet Databases. The Directory is part of the Gale Directory of Databases, published on paper in two volumes each year. It is also available online via Westlaw, http://www.westlaw.com/. It is not clear what the relationship between the paper Directory and the electronic version have to one another, although the first volume of the paper Directory has the same title, and perhaps the same contents, as the version available online. Due to limited access to the paper Directory, no effort was made to verify this. 13 For discussion of the quantity of undercounting, see Clemente Forero-Pineda, “Scientific Research, Information Flows, and the Impact of Database Protection on Developing Countries,” from Open Access and the Public Domain in Digital Data and Information for Science, Proceeding of an International Symposium, National Research Council of the National Academies (2004). 4 Is there a problem that new rights in databases will solve? As good a resource as it is, the Directory cannot answer the preliminary policy question, at least not alone. Before examining methods of remedying the database underproduction problem one must first determine that there is, in fact, a problem and the Directory cannot provide that negative evidence directly. It is worth noting, however, that the United States produces and sells more databases than any other nation, and that the growth of this industry is and has been greater than in Europe. If the United States is facing the sort of database underproduction that might warrant legislative intervention and the creation of new rights (and thus new burdens), it is certainly not the worst off of the nations. Moreover, the database industry is economically viable in the United States, and has experienced robust growth in the number of databases sold, and the revenue generated thereby. For instance, the 2002 Economic Census indicated that over the 5year period from 1997 to 2002, the number of companies classifying themselves as database publishers grew by around 25% (from 1,458 to 2,098), receipts grew by 50% (from $12.3 B to $18.8 B), and payroll in the industry nearly doubled (from $1.7 B to $3.2 B).14 In fact, there is little reason to believe that there is an essential market failure in the United States leading to database underproduction. Database production has traditionally been strong in this country, and it is getting stronger. For instance, in response to a 1998 effort to create new database protections, one witness testified that the number of databases in this country had increased 35% over a six year period, the number of files within databases had grown 180%, and the number of online searches had grown 14 2002 Economic Census Information Industry Series, Directory and Mailing List Publishers, Report No. EC02-511-04, November 2004. Available at http://www.census.gov/epcd/ec97/industry/E51114.HTM. 5 80% in the same time.15 Apparently US database providers have not been sufficiently discouraged by the state of the law to cut back production. Indeed, individual US investment in databases must have been climbing over the period, because the number of players in the industry increased only 10% over the period. Does strong database protection lead to increased incentives, and increased database production? According to the Directory, online database production may not have increased as a result of the Directive.16 Indeed, the Directive may have had no effect at all- production of online databases stayed nearly flat after the directive was implemented. In some countries, the number of new databases created each year fell after implementing the Directive. And the correlation between implementation and new database production is statistically insignificant – the presence or absence of implementing legislation explains just over 1% of database production. Some researchers, writing in 2001 and thus without the benefit of later data, have written that the Directive has, in essence, failed.17 They argue that, aside from a brief spike in total database production immediately after implementation, preceeded by a commensurate decline in production while firms anticipated the new legislation, the Directive has had no obvious effect and database production has fallen to pre-Directive Band, supra note 6, citing Martha E. Williams, “The State of Databases Today: 1998”, in Erin E. Holmerberg, ed., Gale Directory of Databases, p. xvii (September 1997). 16 The Directory was queried electronically, using Westlaw’s interface, for databases identified as originating in each country in each year between 1994 and 2003, inclusive. Only the databases that were new to the directory in each year were reported. The total number of responses to each query were then plotted. Thus, each data point represents the number of new databases in each country in each year. The queries counted only database creation; no attempt was made to count the number of databases that ceased being available in any year. 17 Stephen M. Maurer, P. Bernt Hugenholtz, Harlan J. Onsrud, “Europe’s Database Experiment,” Science Vol. 294, Num. 26 (October 2001). For more concrete data, see Stephen M. Maurer, Suzanne Scotchmer, “Across Two Worlds: Database Protection in the US and Europe,” in J. Putnam, Intellectual Property and Innovation in the Information-Based Economy, forthcoming. 15 6 levels. This, they take it, is empirical evidence of the reasons not to adopt strong protection. On the other hand, as has been pointed out elsewhere this is at best negative evidence.18 The lack of correlation tells us only that other factors affected database production more than new protection measures, not that the measures had no positive effect whatever. Moreover, the United States observed a similar downward trend in online database production over the period; perhaps something about database usage or technology changed during the period to make online publication of databases unattractive. (See Figure 1). In fact, the same period showed exponential growth in the size and consumption of many existing databases, both in the United States and in Europe.19 At least in biological databases, new records were being inserted and the rate of incoming queries was also climbing. Thus data was still being produced, and the European trends appeared to follow American trends in data usage and production. Trends are not quantities, however. For the entire period measured, U.S. online database production outpaced all of Europe by a factor of nearly 2.5:1, even though it fell in America at the same times and rates as in Europe. American dominance of database production cannot be explained by the incentives given to creators because American protection of database rights is much weaker than the Directive. See Hughes, supra note 1. Hughes notably calls the current state of evidence either “a ringing endorsement of the status quo,” or a recommendation that changes should be reactive to observed phenomena. 19 See Mark Gerstein, Dov Greenbaum, “A Universal Legal Framework as a Prerequisite for Database Interoperability,” Nature Biotechnology Vol. 21, Num. 9, pp. 979-82 (September 2003). 18 7 Online Database Production 160 140 120 100 Germany United Kingdom United States Europe 80 60 40 20 0 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Figure 1 Is robust database protection the only or best way to drive new database production? If not protection, then what explains America’s database productivity? The importance of this question to policy-making ought not be gainsaid: if something other than high levels of protection may incent database creation, and may be more efficient in doing so, it ought to be explored and its harmful side-effects compared to those of the current database protection proposals. Certainly other methods of driving database production could be, and have been, successfully employed. For instance, some databases have been considered public sector, and thus left completely unprotected in the United States. The government has explicitly financed these databases, and the resulting spin-off revenue has paid for them many times 8 over.20 This model of database production has proven efficient for at least some kinds of databases (in particular, databases that require government monopolies to generate, or that are best generated in this way, like meteorological and topographical databases). Moreover, several other models for providing incentives to create have been proposed, and their theoretical qualities tested.21 If increased database protection has not benefited the broader public by increasing database production, it has had some effect. Strong database protection means that database creators must expend a great deal of capital; it is no longer possible to legally repurpose the data contained in existing databases in order to cheaply create a new database. Database protection is capital-rich company protection. As such, it runs the risk of actually decreasing database concentration. Perhaps this helps explain some of the overall decline in database production in Europe, although the drop-off in American growth at the same time is striking, and suggestive of broader sources. The NautaDutilh study. The Directive demands that it be periodically reviewed. The reviewing process itself creates more data, and more empirical evidence. The first mandatory deadline described in the Directive has passed, and the report was not forthcoming. However, a See Peter Weiss, “Borders in Cyberspace: Conflicting Public Sector Information Policies and their Economic Impacts,” Summary Report, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Weather Service, (February 2002). Weiss compares American public sector databases, which are distributed for little or even no charge, to some European databases that are distributed under restrictive terms at higher cost and concludes that the American system leads to more and better database production, and higher returns on the databases so developed. 21 In the patent domain, see Nancy Gallini, Susan Scotchmer, “Intellectual Property: When Is It the Best Incentive System? (preprint),” Innovation Policy and the Economy Vol 2, Adam Jaffe, Joshua Lerner and Scott Stern, eds, MIT Press, pp. 51-78, and also forthcoming in Legal Orderings and Economic Institutions, F. Cafaggi, A. Nicita and U. Pagano, eds., Routledge Studies in Political Economy. Available at http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~scotch/G_and_S.pdf. In copyright Maurer and Scotchmer note that technological and market mechanisms have protected American databases. Stephen M. Maurer, Suzanne Scotchmer, “Database Protection: Is It Broken and Should We Fix It?,” Science Vol. 284, Num. 5417, pp. 1129-30 (May 14, 1999). 20 9 review is forthcoming, based primarily on the results of a survey conducted by a private firm under contract. No discussion of the existing empirical evidence could be complete without an exploration of this survey. The first thing to note about the survey is that its results are statistically insignificant, because it had only 45 respondents, and they were not randomly chosen. This does not remove from it all value, but it ought to color one’s reading of the final interpretations of results. The second thing to note is that the respondents self-selected for a certain viewpoint. Of the 45, 10 identified themselves as database publishers, and none identified themselves as consumer protection representatives. The mode represented companies turning over more than 200 million EUR each year, and the majority made at least 50 million EUR, so the answers are all bent towards the interests of large, high-income rights holders (none had less than 50 employees, and the mode had more than 2000). The most important deficiency of the study, however, is that it failed to ask quantifiable questions about the actual effect of the Directive on decision making, but instead required the respondents to assess broad claims about the effect on the decisions of everyone within the system. For instance, rather than asking whether the database owner had sold their database outside of their home country, the survey instead asked that each respondent mark either “I agree” or “I disagree” to statements like, “By eliminating the differences existing between the Member States’ legislation…, the Directive has [had] a positive effect on the free movement of database-related goods or services within the Community.” What is astonishing about the survey is that, despite these obvious biases, nearly twice as many respondents felt that the Directive created an unbalance between the rights 10 of rightsholders and users. Nearly half of those who responded to the question thought the definition of a database in the Directive was either too broad or too uncertain. None thought it too narrow. A healthy majority thought the substantial investment threshold for so-called sui generis protection was too uncertain. Respondents were split down the middle on whether the creation of sui generis protection was satisfying. Most thought such rights too broad. Many noted that the permitted exceptions were too narrow. Conclusion The debate over whether to offer databases additional protection beyond copyright has focused on the theoretical economic arguments on both sides of that issue. The arguments have been suspiciously devoid of evidence. In fact, evidence does exist, but it is both hard to find, and difficult to meaningfully analyze. The current state of American database production suggests that there is no problem to be corrected. The number of companies producing databases is growing moderately. The number of databases those companies are producing is growing much more quickly, and the number of entries in those databases is exploding exponentially. Moreover, the industry has experienced handsome revenue growth, has created new jobs, and is poised to grow even more in the future. All of this despite the fact that America does not offer strong, legislated database protection. Current database publishers rely on a combination of self-help mechanisms to protect their investments, and the mechanisms work. The situation in Europe is not as happy, despite the strong database protection that exists as a result of the European Database Directive. Database growth has been moderate, at best, and not much better if better at all than it was before the Directive. 11 Moreover, despite the assertions of proponents of strong protection, even database producers are unhappy with many unforeseen aspects of the Directive and its effects. That said, it would be premature to conclude from the evidence that database protection simply does not work to spur new production. Other explanations cannot be ruled out, including the simplest that complex database protection schemes will take a long time to have any appreciable effect. Thus, if there is a problem then database protection might be a way to solve it. There are other good ways to solve it, however, and they have not been explored significantly. Public sponsorship of database production, including direct contract payments for certain kinds of work, have been remarkably successful in producing a robust and high-quality database industry. Even better, publicly funded and generated databases may be made available for reutilization at little or no cost, which might then drive other productive activities. Because data is an input to most modern production, systems that spur data production and dissemination have much to recommend them. 12 Appendix: Data and Analysis The Gale Directory was queried on Westlaw. Each data point was created by searching for: ‘CN(“country”) AND YR(year)’. The total number of responses to the query for each country and year were compiled into the following table. The highlighted entries indicate the years in which the legislation incorporating the European Database Directive took effect. Austria Belgium Denmark Finland France Germany Greece Ireland Italy Luxembourg Netherlands Portugal Spain Sweden United Kingdom United States 1994 0 4 0 0 2 20 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 0 9 1995 1 2 4 0 3 13 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 16 1996 1 3 1 3 2 5 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 2 8 1997 2 0 1 3 3 10 0 0 1 1 5 0 0 1 28 1998 0 1 0 1 1 9 0 1 0 0 2 0 0 0 48 1999 2 12 1 0 1 7 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 74 2000 0 0 2 1 1 7 0 0 2 1 1 0 0 0 14 2001 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 1 2 2002 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 2003 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 86 125 111 145 122 136 85 32 7 5 The data was then analyzed for correlations between implementation of the European Database Directive and the number of new databases listed in the Gale Directory. The correlation was calculated to be 0.012644, or about 1.3%. The United Kingdom presents the obvious outlier among European countries, and Germany was highly productive over the period as well. On average, Europe produced 35.87 new databases in the Directory before implementing the Database Directive, and 38.08 after, a 6% boost. However, this is largely due to the UK; without United Kingdom production, Europe produced 21.62 databases per year on average before implementation, and only 11.47 after, a decline of 47%. The United States added an average of 85.4 new online databases each year over the period. 13