Extended abstract

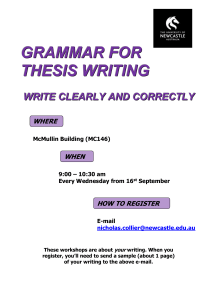

advertisement

Deconstructing female conventions: Ann Fisher Maria E. Rodriguez-Gil University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria e-mail: mariarodgil@telefonica.net Ann Fisher, daughter of a yeoman, decided not to follow conventions. She led her life in the public sphere, not happy with the prevailing idea that women should be educated for a life at home. Women education during the eighteenth century was restricted to moral and social education within the domestic environment, acquiring those skills that would help them in their pursuit of a husband. Their intellectual abilities were considered quite low. So much so, that women with a sound knowledge in any subject were looked suspiciously since it ‘was seen to compromise a woman’s feminity’ and ‘consequently, excessive learning was believed to spoil a woman’s chances on the marriage market’ (Tieken 2000a: 342). However, Fisher was not satisfied with the basic education in the “polite knowledge” given to women, which covered geography, history, poetry or painting (Goldsmith 1979: 316). She aspired to deeper knowledge and she sought for it. She learnt Latin and was a customary reader of contemporary press and scholastic work. For instance, this author mentions in her grammar work authors such as John Clark (1733), Nathaniel Bailey (1706), and quotes from Ephraim Chambers and his work Cyclopaedia (1738), and from Addison’s writings on several grammatical aspects of the English language in the Spectator. This versatile woman also hosted, together with her husband, a club that gathered the prominent local people where discussions on ‘topics of current interest exerted an elevating influence on local aspirations and habits’ (“The Newcastle Chronicle” 1890: 223). Fisher surrounded herself with the cultural elite of Newcastle, the town where she spent most of her life. She could boast among her friends such prominent figures as the writers Mr. Robertson, Robert Carr and John Cunningham, the engraver Thomas Bewick, and Gilbert Gray, owner of a local paper, The Independent Whig, and author of several books. Though Fisher was a devoted wife and mother, she got married aged thirty-two and had nine daughters, she became a prosperous business woman, both before and after her marriage, as well as a prolific author of educational books. As a business woman, she ran her own ladies’ school for young ladies for at least five years before her marriage. Besides, she started and managed together with her husband a shop, a printing office and a local newspaper, The Newcastle Chronicle. But she also stood out in the world of arts, being the author of several educational books, namely a grammar of the English language, an anthology of short texts which aimed at inculcating moral principles, a spelling book, an exercise book, a dictionary of the English language, and a compendium of geography and astronomy. She also undertook the edition of a ladies’ memorandum book, which was really popular with at least 1000 copies per year, and which included, among other things, original poetry, enigmas, engravings for patterns of ladies’ dresses and a calendar (Bell 1835?). Fisher’s unconventional lifestyle affected her literary work, which is obvious in her most popular book, a New Grammar, with Exercises of Bad English (1750). This work made her the first female grammarian (Tieken 2000b: 1) and it became the most popular English grammar written by a woman (Percy 1994: 123). Another reason that makes A New Grammar outstanding is that it was written in a provincial city in the north, in Newcastle, and not in London, the centre of print culture by then. Though it is even more relevant that it achieved such popularity that several editions of her work were printed in London. But this grammar is also important on its own. The author did not write for a learned audience, but for mere English scholars who had little or no Latin, as well as for young ladies, as Fisher states in the preface to her grammar (1750: v-vi). In so doing, Fisher was opposing, on the one hand, those contemporary English grammarians who held that to learn English was necessary a knowledge of the classical languages, i.e. Latin or Greek; and, on the other hand, she was addressing a female audience, whose study was very much neglected during the eighteenth century since, as Hill has stated (1993: 44), women were considered intellectually inferior to men. Fisher wrote an English grammar based on the nature and observation of her mother tongue, becoming thus a strong detractor of making English grammar fit the Latin pattern, a common practice still in the eighteenth century. She criticises categorically those grammarians who wrote Latinate English grammars and defends the teaching of English independently from Latin grammar. So much so, that Percy has said that Fisher’s grammar ‘was in fact associated with a repudiation of Latin’(1994: 123). Besides, this grammarian adopted a vernacular terminology for the description of the grammatical terms and divided the grammatical categories into four parts, namely nouns, adjectives, verbs and, under the label of “particles”, she comprised prepositions, interjections, adverbs and conjunctions. These two features makes Fisher the only woman listed among the eighteenth-century English grammarians of the “movement of reform” (Michael 1985: 509-10). The author also combined in her grammar both the prescriptive and descriptive approaches to language analysis, opposing thus to the division that has been traditionally made between descriptive and prescriptive grammar as two mutually exclusive approaches to language analysis. There is still another characteristic that made her English grammar out of the main stream, its methodological innovations. Many grammars written in the eighteenth century did not pay attention to how the material was presented. In contrast, we find in Fisher’s grammar a method to teach grammar, an abstract of the grammatical categories, and a new type of grammatical exercise. This new exercise became strikingly popular as it was the second most popular school exercise after parsing, and it was included in about eighty 18th and 19th century English grammars (Michael 1987: 325, 327). All these innovations made her English grammar most welcome by contemporary readers, since her grammar saw almost forty editions and reprints, and it reached other markets, such as London and Leeds. References ADDISON, Joseph. 1789. The Spectator. 8 vols. VI. II. London: H. Hughs, BAILEY, Nathaniel. 1706. English and Latin Exercises for School-Boys, to Translate into Latin Syntactically, Comprising all the Rules of Grammar. London: James Holland. BELL, John. 1835?. Newcastle Booktrade Advertisements, Cuttings, Trade-Cards, Leaflets, and other Ephemera. Newcastle upon Tyne; n.p. CHAMBERS, Ephraim. 1738. Cyclopaedia; or, a Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. London: printed for D. Midwinter and others. CLARK, John. 1733. A new Grammar of the Latin Tongue, comprising All in the Art Necessary for Grammar-Schools. London: A. Bettesworth & C. Hitch. FISHER, Ann. 1750. A New Grammar with Exercises of Bad English; or, an easy Guide to Speaking and Writing the English Language. Newcastle upon Tyne: printed for I. Thompson and Co. by J. Gooding. GOLDSMITH, Peter L. 1979. “Ambivalence towards women’s education in the eighteenth century: the thoughts of Vicesimus Knox II”. Paedagogia-Historica 19: 31527. HILL, Bridget. 1993. Eighteenth-Century Women: an Anthology. London and New York: Routledge. MICHAEL, Ian. 1985. English Grammatical Categories and the Tradition to 1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. _____________ 1987. The Teaching of English from the Sixteenth Century to 1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. “The ‘Newcastle Chronicle’”. 1890. in The Montholy Chronicle of North Country Lore and Legend. 5 vols. Vol. 4. Newcastle upon Tyne: Walter Scott, 223-6. PERCY, Carol. 1994. “Paradigms for their sex? Women’s grammars in late eighteenthcentury England”. Histoire Epistemologie Langage 16/II: 121-41. TIEKEN-BONN VAN OSTADE, Ingrid. 2000a. “ A little learning a dangerous thing? Learning and gender in Sarah Fielding’s letters to James Harris”. Language Sciences 22: 339-358) ______________ 2000b. “Female grammarians of the eighteenth century”, Historical Sociolinguistics and Sociohistorical Linguistics. http://www.let.leidenuniv.nl/hsl_shl/femgram.htm