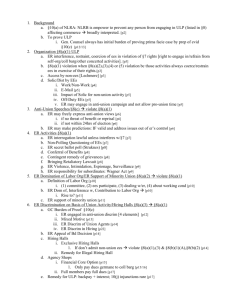

Labor Law Outline

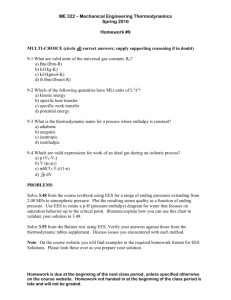

advertisement