Nurse practitioners in the Pediatric Emergency Department – their

advertisement

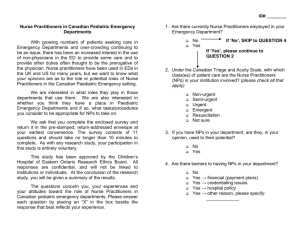

Pitters – Nurse Practitioners Nurse practitioners in the Pediatric Emergency Department – their current roles and physician attitudes towards their role Principal Investigator: Carrol Pitters1, MD Co-Investigators: Shane English2, BSc., Amy Plint1, MD, Tammy Clifford, PhD3 Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario/University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario 1 2 Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario Chalmers Research Group, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute and Departments of Pediatrics and Epidemiology & Community Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario 3 -1- Pitters – Nurse Practitioners Objectives: The objectives of this study are: (1) to determine the current utilization of Nurse Practitioners (NPs) among academic paediatric emergency departments (ED) in Canada and (2) to examine paediatric emergency department physicians’ attitudes and confidence in NPs assuming traditional physician duties. Background: Over the past decade, the role of the Emergency Nurse Practitioner (ENP) has been well established in Accident and Emergency (A&E) departments in the United Kingdom (Read et al. 1992; Tye et al., 2000; Cooper et al. 2001). By 1991, 6% of A & E departments in England and Wales had implemented the NP role (Read et al. 1992). It is now estimated that as many as 30-70% of A & E departments in some areas have implemented the role (Cole and Ramirez 2002). The initial role of the NP in emergency care in the United States resulted from a need to provide care for a growing number of non-urgent patients presenting for health care to rural emergency departments (Curry, 2000). NPs now provide services in various ED settings, and guidelines for the role of NPs in emergency departments have been endorsed and published by the American College of Emergency Physicians with the last update in June 2000 (ACEP, 2000). In Canada, the initial role of the Nurse Practitioner was in primary care, and the first training program was established in the 1960s for NPs working in northern nursing stations (NPAO, 2001). Today, the most common setting for NPs is in community clinics, but with the recent strains in emergency services delivery, interest has been expressed in the possible role of the NP in emergency departments. In April 2001, the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians and the National Emergency Nurses Affiliation published a joint position statement on emergency department overcrowding (CAEP & NENA, 2000). They outlined multiple contributing factors and proposed several strategies to address some of the problems associated with over-crowding. They suggested the implementation of Nurse Practitioners (NPs) in Emergency Departments as one of these strategies (CAEP & NENA, 2000). Definition of NP A Nurse Practitioner is a registered nurse (RN) who has advanced training in diagnosing and treating illness (NPAO, 2001). Nurse Practitioners prescribe medications, treat illness, and administer physical exams. NPs differ from physicians in that they focus on prevention, wellness, and education. NPs specialize in providing all-encompassing individualized care. Most NPs specialize in particular areas of health care (NPAO, 2001). Why is this study necessary? Studies have been undertaken in the US on the role of NPs in emergency departments and on attitudes toward them (Alongi et al., 1979; Cairo, 1996). In Canada, however, there are no data on the number of pediatric emergency departments that employ NPs nor do we know the nature of NPs’ roles within these departments or physicians’ views regarding which current physician duties they believe NPs could assume (including -2- Pitters – Nurse Practitioners patient care and administrative duties). Collecting such information is an essential first step in understanding possible benefits and roles of NPs in the pediatric ED, possible barriers to implementing NP programs, and assessing the efficacy of NPs in the pediatric ED. Our study will be the first to ascertain the number of Canadian pediatric EDs that now have ENPs as part of their ED staff, to characterize the roles of ENPs within these environments and to assess the attitudes of pediatric Emergency physicians to the ENP in the PED. Methods: Study Design: Descriptive, cross-sectional, national survey. Justification/Rationale for Design: Given the absence of empirical data regarding the utilization of NPs within Canadian pediatric emergency departments, their current roles within these departments, and physician views regarding their duties, a descriptive survey reflecting current practice and views is a logical starting point. Findings of this initial survey will serve to direct future research, including permitting the generation of hypotheses that can be subjected to formal evaluation. Sampling Procedures: Because there are only 10 pediatric EDs in Canada, all of them will be surveyed and so this study forms a census and no sampling, per se, will be required. The typical disadvantages of a census in terms of costs and time required to obtain information from an entire population are not of concern here as our population of interest is so small. Eligibility Criteria: All physicians whose primary clinical appointment is to one of the 10 pediatric emergency departments in Canada will be eligible for study participation. Sample Size: There are 10 pediatric hospitals with EDs in Canada. A list of physicians in these departments has previously been compiled and will be used. Data Collection: Each pediatric emergency physician will be contacted directly via mail. Each survey package will contain the appropriate survey instrument with an explanation of the study and a pre-stamped, return-addressed envelope in which to return the completed questionnaire. This method of data collection was selected because selfadministered questionnaires are cheaper to administer than other methods (e.g., in-person, telephone) (Fink, 1995). Postal surveys also permit wide geographic coverage; this is an important consideration in this survey as we intend to reach a national audience. Also, respondents may be more likely to complete a mailed survey since they can do so at their convenience. In order to ensure our results are as robust as possible, concerted efforts will be made to encourage responses from all individuals. This will use a modified version of Dillman’s Total Design Survey Method (Dillman, 2000). In this approach, all doctors will be mailed the appropriate questionnaire with a pre-stamped, return addressed envelope in which to return the completed questionnaire. A reminder postcard will be mailed to all participants one week after the initial mailing; another copy of the questionnaire will be sent after a further 2 weeks, and again 2 weeks after that, to the remaining nonrespondents. To ensure anonymity, the questionnaires will be coded so -3- Pitters – Nurse Practitioners that the investigators will be unaware of the names of the residents completing the questionnaires. Tracking of responses, subsequent mailings to non-respondents and data entry will be performed by a Research Assistant who has no contact with study participants. . Survey Instruments: Two survey instruments have been developed and piloted. Their content was based in part on work of previous authors (Cole and Ramirez, 2000a, 2000b). The first instrument, for Medical Directors of Pediatric Emergency Departments, will examine the demographics of the individual emergency department (such as ED census, proportion of patients per triage category, presence of a “fast track” service and current use of NPs). A second survey will be sent to all pediatric emergency physicians and will collect demographic information, their opinions and comfort level regarding NP patient management. The surveys comprise a series of single- and multiple-select closed ended items; however, some items also allow for selection of a residual "other" category. In cases where the respondent feels that their response did not correspond to those already listed (i.e., they selected "other"), they are asked to elaborate upon their answer in fulltext. The surveys will be translated into French by the translation service at CHEO, to facilitate the collection of information from sites in Quebec and elsewhere. It is estimated that the surveys will take a maximum of 10 minutes to complete. Data Analysis: Descriptive statistics will be determined for all measures. Frequencies of responses to questionnaire items that solicited information on NPs current roles and physicians’ attitudes towards NPs assuming duties will be tallied. Bivariable analyses will examine the relationships between respondents’ demographics and practice settings (e.g., site, patient census, length of time in practice, level of training) and the variables that relate to NPs current roles and physicians’ attitudes towards NPs using the Mantel-Haenszel chisquared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. For example, one such comparison will juxtapose years of experience versus physicians’ opinion as to what class(es) of patient care they would be comfortable with an ENP managing without supervision. In all cases, because this survey aims to generate, rather than test, hypotheses, adjustments will be made for multiple testing by setting alpha at 0.01 rather than 0.05. Dissemination Plans: Findings will be disseminated at national and international paediatric conference as well as by publication in a relevant peer-reviewed medical journal. Ethical Considerations: This proposal will be submitted to the Research Ethics Board of the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario for review. There are no anticipated risks associated with participation in this study. Participation by the survey recipient is voluntary; consent to participate in this research by the respondent will be assumed with receipt of a completed survey. Participants can not be sanctioned by their program/institution for choosing not to participate or not completing their survey in its entirety. All precautions will be taken to assure participants’ confidentiality; only participant identification numbers (PINs) will appear on survey instruments. A database that links PINs with participant names and -4- Pitters – Nurse Practitioners sites will be kept geographically separate from the study forms. This database will be prepared by the research assistant and will not be available to the investigators, so that anonymity is maintained. The research assistant has no direct interest in the research results. All information collected will be held in strictest confidence and will be kept in locked cabinets in the research office. When the study is completed only aggregate data will be reported; neither participants’ nor institutions’ identities will be revealed. References ACEP (2000). Guidelines on the role of nurse practitioners in the emergency department. www.acep.org./1,583,0.html (accessed 4-April-2002). Alongi S, Geolot D, Richter L, Mapstone S, Edgerton MT, Edlich RF. (1979). Physician and patient acceptance of emergency nurse practitioners. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians 8: 357-359. CAEP and NENA. (2001). Joint position statement on emergency department overcrowding. Cam J Emerg Med 3; 82-84. Cairo MJ. (1996). Emergency physicians’ attitudes toward the emergency nurse practitioner role: validation versus rejection. J Am Acad Nurs Practitioners 8: 411417. Cole FL, Ramirez E. (2000a). Nurse practitioner autonomy in a clinical setting. Emerg Nurse 7; 26-30. Cole FL, Ramirez E. (2000b). Activities and procedures performed by nurse practitioners in emergemcy care settings. J Emerg Nursing 26; 455-463. Cole FL, Ramirez E. (2002). A profile of nurse practitioners in emergency care settings J Am Acad of Nurse Pract 14:180-84. Cooper MA, Hair S, Ibbotson TR, Lindsay GM, Kinn S. (2001). The extent and nature of emergency nurse practitioner services in Scotland. Accident and Emergency Nursing 9:123-129 Curry JL. (1994). Nurse practitioners in the emergency department: current issues. J Emerg Nurs 20: 207-215. Dillman D. Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000 Fink A. The Survey Handbook, 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks California: Sage Publications, 2003. -5- Pitters – Nurse Practitioners Hayden ML, Davies LR, Clore ER. (1982). Facilitators and inhibitors of the emergency nurse practitioner role. Nurs Res 31; 294-299. NPAO. (2001). Role of PHC and AC NP’s. www.npao.org/role.html (accessed May 15, 2002) Read SM, Jones NMB, Williams BT. (1992) . Nurse Practitioners in Accident and Emergency Departments: what do they do? BMJ; 305:1466-70 Tye CC, Ross FM. (2002). Blurring boundaries: professional perspectives of the emergency nurse practitioner role in a major accident and emergency department. J Adv Nurs; 31:1089-1096 Widhalm SA, Anderson LA. (1982). Emergency nurse practitioners: motivators, barriers, and autonomy in role performance. J Emerg Nurs; 8:67-74 -6-