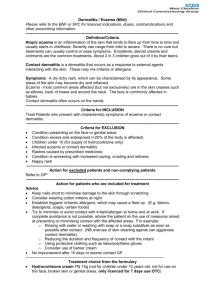

Contact dermatitis is a skin condition characterized by itching

advertisement

Contact Dermatitis: A Major Occupational Health Problem Introduction Contact dermatitis is a common skin condition characterized by itching, redness, cracks, dryness and pain. It is responsible for over 5.6 million doctor visits each year and accounts for 15% - 20% of all reported occupational diseases (CDC). Generally, contact dermatitis is caused by exposure to detergents or solvents or by sensitization after repeated exposure. Eighty percent (Leung) of contact dermatitis cases are irritant related in which the irritant directly damages the skin. Even repeated exposure to mild soaps and water can cause such irritation. The increased skin humidity associated with prolonged glove use, can also cause irritant contact dermatitis. The remaining 20% of contact dermatitis cases are allergic in nature. In these cases the irritant induces an allergic response as is commonly seen among health care workers with a hypersensitivity to latex gloves. Specific Issues for Health Care Workers Exposure In a recent study of skin damage on the hands of nurses (Larson), over 85% of nurses surveyed reported having problems with their hands at some time (and an equal percentage reported improved skin after time off from work). These problems can be traced back to three leading causes of contact dermatitis among heath care workers: 1. Frequent hand washing and drying: Frequent hand washing causes the removal of the lipid layer of skin making it prone to irritation. Incomplete hand drying after washing can exacerbate skin irritation. Universal precautions mandate frequent hand-washing and drying – nurses wash their hands, on average, 30 times per shift, 20 seconds per wash . Nurses reported hand washing as the major contributor to the condition of their skin. 2. Repeated use of latex gloves: Universal precautions mandate that gloves be worn for almost all medical procedures. Over 96% of nurses wear latex gloves. 7% to 10% of all health care workers show hypersensitivity to latex. Nurses change gloves, on average, 22 times per shift. 3. Use of Cleansers and Other Chemicals: Over 75% of nurses use a harsh anti-microbial soap when washing their hands. 1 Nurses who use antimicrobial soaps were more likely to have skin damage than nurses using non-antimicrobial soaps or antimicrobial washes. Risks Due to Exposure Contact dermatitis itself is not a contagious condition and does not pose a direct risk to other staff and patients. However, a consequence of contact dermatitis is an increased risk of microorganisms, yeasts, and bacteria carried on the skin as well as an increased risk of shedding these microorganisms. Consequently without treatment, crossinfections by hospital staff with contact dermatitis to patients and other staff are possible. Risk Management To minimize the risks of cross-infections due to contact dermatitis, health care workers first need to recognize the risks and the symptoms of contact dermatitis itself. Many health care workers do not know that they are at risk for contact dermatitis as they do not consider themselves exposed. Additionally, studies have found that a history of hand eczema (dryness, itchy, scaling) increased the odds of acquiring contact dermatitis (Meding). Consequently, health care workers with a history of eczema should be especially on the alert for problems. Current Treatments The primary prevention and treatment for contact dermatitis is simple avoidance of the causative agent. For the majority of health care workers this is simply not possible – frequent hand washing with an anti-microbial soap and glove use are required practices for effective infection control. Once contact dermatitis is diagnosed, antiseptic hand creams and protective lotions should be used to reduce the number of microorganisms on the skin as well as the risk of shedding these organisms. To treat existing hand problems, a majority of nurses reported using non-prescription hand lotion, 9% used vaseline or lotion under gloves at night, and 8% used a prescription product (Larson). When prescriptions are required, topical corticosteroid creams are typically prescribed. In severe cases, an oral corticosteroid may be used for a short time. To prevent allergic contact dermatitis, health care workers with a known hypersensitivity to latex should switch to a non-latex glove made of vinyl or nitrile. Even the replacement of powdered latex gloves with unpowdered latex gloves has been shown to reduce the symptoms of contact dermatitis in those with latex hypersensitivity. A major difficulty with all existing treatments is that they may relieve symptoms temporarily, however, they will not promote healing. 2 Costs There are no published cost of illness studies on contact dermatitis. However, effective treatment and management of contact dermatitis is not without costs. Health care workers with a hypersensitivity to latex may benefit from replacing powdered latex gloves with non-powdered latex gloves. For exam gloves, the cost differential is nominal; for sterile surgical gloves, however, there is a five to six-fold cost increase associated with the non-powdered gloves. A recent study (Larson) showed that nurses using a handwashing product containing chlorhexidine gluconate such as Hibiclens reported significantly fewer problems with their hands than nurses using a bar soap such as pHisoDerm. However, a switch to the gentler product would result in an increase in cost. Costs for a non-prescription hydrocortisone cream are approximately $15 per month. A prescription product would cost about $35 per month. Though not as quantifiable, there are also large costs – both personal and financial – to not treating and suffering from chronic contact dermatitis. Quality of life issues, crossinfections and lost productivity top the list of costs associated with lack of treatment. Proposed Disease Management In general terms, disease management programs consist of a variety of activities designed to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of care received by patients with particular diseases. A disease management program for contact dermatitis, aimed at nurses and other health care professionals, would likely consist of an education program to increase awareness of the condition, as well as information on how to effectively prevent it. Risk management awareness as described above would also play an important role. The likely results from a disease management program for contact dermatitis would include: a reduction in costs related to sick leave, doctor visits, and job-related inefficiency; higher quality care resulting from fewer outbreaks of the condition; and a more satisfying work environment. This independent research report was prepared by The Lewin Group, a division of Quintiles Transnational Corporation, that specializes in Disease Management and Pharmacoeconomic Analysis for government and managed care organizations. Contact: Catherine Harrington, Vice President, 703-218-5730, Proteque International, a dermatitis disease management company in Raleigh, North Carolina, 800-953-9250, sponsored this research as a public service educational project to Hospital, HMO, Research, Long Term Care, Dental and Nursing Professionals. 3 References: Bernstein, D. 1997. “Allergic reactions to workplace allergens,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 278(22), pp. 1907-13. CDC National Institute of Occupational Health, Update July 1997. Dahl, M. 1988. “Chronic, irritant contact dermatitis: mechanisms, variables, and differentiation from other forms of contact dermatitis,” Advanced Dermatology, Vol. 3, pp. 261-75. Frantz, S., et al. 1997. “Chlohexidine gluconate (CHG) activity against clinical isolates of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VREF) and the effects of moisturizing agents on CHG residue accumulation on the skin,” Journal of Hospital Infection, Vol. 37(2), pp. 157-164. Grunewald, A., et al. 1995. “Damage to the skin by repetitive washing,” Contact Dermatitis, Vol. 32(4), pp. 225-32. Holness, D., et al. 1995. “Exposure characteristics and cutaneous problems in operating room staff,” Contact Dermatitis, Vol. 32(6), pp. 352-58. Kersbergen, Anne. 1996. “Case Management: A Rich History of Coordinating Care to Control Costs,” Nursing Outlook, Vol. 44, pp. 169-72. Larson, E., et al. 1997. “Prevalence and correlates of skin damage on the hands of nurses,” Heart & Lung, Vol. 26, pp. 404-12. Le, T., et al. 1998. “A histological and immunohistochemical study on chronic irritant contact dermatitis,” American Journal of Contact Dermatitis, Vol. 9(1), pp. 23-28. Leung, D., et al. 1997. “Allergic and immunologic skin disorders,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 278(22), pp. 1914-23. Meding, B. & Swanbeck, G. 1990. “Predictive factors for hand eczema,” Contact Dermatitis, Vol. 23(3), pp. 154-61. Nilsson, E., Mikaelsson, B., & Andersson, S. 1985. “Atopy, occupation and domestic work as risk factors for hand eczema in hospital workers,” Contact Dermatitis, Vol. 13(4), pp. 216-23. Singgih, S., et al. 1986. “Occupational hand dermatoses in hospital cleaning personnel,” Contact Dermatitis, Vol. 14(1), pp. 14-19. 4 Smack, David, et al. 1996. “Infection and allergy incidence in ambulatory surgery patients using white petroleum vs bacitracin ointment,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 276(12), pp. 972-77. Smit, H. & Coenraads, P. 1993. “A retrospective cohort study on the incidence of hand dermatitis in nurses,” International Archives of Occupational Environmental Health, Vol. 64(8), pp. 541-44. Stingeni, I., Lapormada, V., & Lisi, P. 1995. “Occupational hand dermatitis in hospital environments,” Contact Dermatitis, Vol. 33(3), pp. 172-76. Sussman, G & Beezhold., D. 1995. “Allergy to latex rubber,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 123(3), pp. 234-35 Copyright ©1998 by Protèque International 5