CHINA: THE IMPORTANCE OF IDEOLOGY

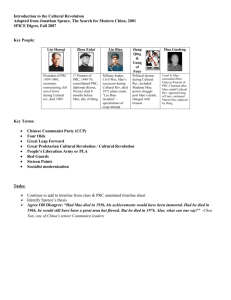

advertisement

1 Chapter 16: COMMUNIST CHINA: An Historical Overview and the Importance of Ideology (Written 1989; Revised 2006) With its victory over the Nationalist government in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party came to power. The communist party leaders agreed that the country needed to develop economically and that such development was to occur within a socialist framework. However, since 1949, there have continually been major disagreements as to the ways by which these goals would be accomplished. Until 1976, the main disagreements were between party chair Mao Zedong and his followers (who will be called “radical leftists”) and a more moderate group of party leaders led by Liu Shaoqi and then by Deng Xiaoping (who will be called “pragmatists” or “moderates”). Following the death of Mao in 1976, the “pragmatists” became dominant and China entered a period of major reform. From 1949 to 1976, Mao’s ideology was the dominant influence on Chinese economic policies. In the ten years prior to his death (1966 to 1976), his ideology could be likened to a state religion. Several features of this ideology should be kept in mind as we attempt to understand the peculiarities of China’s economic history. First, Mao believed that people, through sheer human willpower, could accomplish practically any end. This belief developed from his quarter century as a leader of a guerilla revolutionary army. The “guerilla mentality” carried over into economic matters in his belief that people, if properly mobilized, were more important to economic development than capital or technology. Second, unlike Marx, Mao believed in the primacy of politics over economics. You will see below how the Cultural Revolution illustrates Mao’s belief in the primacy of politics. Third, following from this elevation of the role of politics was Mao’s desire to eliminate “economic man” and replace him or her with “communist man”. Communist man would be selfless and capable of total self-denial. He would be one whose main motivation is to benefit the group. You will see this belief illustrated by Mao’s advocacy of “moral incentives” for peasants and workers and his repudiation of material incentives. To Mao, allowing any type of “capitalist” incentives (such as higher pay) would necessarily lead to a reversion to capitalism. Fourth, for Mao, an equal distribution of income was at least as important as economic growth. This included equality between men and women. Finally, Mao saw class struggle and revolution as a continuing process and not as a process that would end with the revolution. He saw a continuing tendency to revert to capitalism that had to be continually fought. As a result of this need for continual revolution, China’s economic history is extremely unstable--- reverting from one set of programs to another and then back again. In examining this instability, we will look four at specific sub-periods: (1) 1949 to 1958, (2) The Great Leap Forward (1958 to 1961), (3) 1961 to 1978 interrupted by the Cultural Revolution (1966 to 1969), and finally (4) the Reform Period (1978 to the present). The first three of these period comprise what we can call “the Socialist period”. 2 (1) 1949-1958 The first decade following the Communists coming to power was a period of recovery from the destruction caused by years of war and revolution. It should not be too surprising that at this time the Chinese attempted to create an economic system similar to that of the Soviet Union. In fact, aid from the Soviet Union helped finance Chinese industry in this period and the Soviet Union provided important technical assistance. Financial aid from the Soviet Union was used mainly for 156 large, integrated plants (“integrated” means that they produced at several different stages of the production process). This has been called the largest technological transfer between countries ever attempted. The influence of the economic system of the Soviet Union in this period is shown in three important ways. First, agriculture was collectivized. A land reform took-place between 1949 and 1952 that virtually eliminated the landlords and rich peasants as social classes. This was followed by the merging of the rural population into more advanced types of cooperatives until finally, in 1958, most of the rural population were organized into communes. Private ownership in agriculture was virtually eliminated within a six month period. This process will be described in detail in Chapter 17. Second, wholesale trade, retail trade, and most of industry came under complete government control by 1956. Enterprises “belonged” to a Ministry, as in the Soviet Union. This nationalization was done without much difficulty, as much of industry had been owned by the Japanese or by the Nationalist government. In 1957, there was a major decentralization, with some control of industry transferred to lower levels of government. But industry was still under the control of some branch of government. The government also controlled managerial career paths and incentives through the nomenklatura system. Third, in 1953, China launched its first five-year plan, modeled on the Soviet materials balance planning system. China adopted the “Big Push” strategy. Investment spending was promoted greatly while consumption was restricted. Large industrial projects were favored despite China’s large number of workers and shortage of capital goods. Between 1952 and 1978, the share of Chinese GDP accounted for by industry rose from 18% to 44%. Because of the decentralization that began in 1957, Chinese planning was less tightly controlled than that of the Soviet Union. At its peak, the central government in China planned for 600 different commodities, compared to over 60,000 in the Soviet Union. Fourth, through the planning system, prices were artificially set by the government. That is, prices did not reflect demand and supply. Prices were artificially high for industrial goods and artificially low for agricultural goods. This was the way for the government to extract resources from agriculture for use in industry. The “profits” of the industrial enterprises were the main source of government revenue. Fifth, wages were also set by the government. They were low and were rarely changed. Throughout the socialist period, strong restrictions were placed on worker mobility, especially between rural and urban areas. Incomes were much higher in urban areas than in rural areas. 3 (2) The Great Leap Forward, 1958 to 1961 The first important manifestation of Mao’s belief in what could be accomplished by sheer human willpower came with the Great Leap Forward. In agriculture, the Great Leap Forward is associated with the rapid establishment of the commune (see Chapter 17). The communes were extremely large and had both economic and governmental functions. Mao had advocated the rapid establishment of communes as a way to overcome the tendencies to revert to capitalism. The “pragmatists” had opposed it, believing that collectivization in agriculture should come after the country industrialized. As we will see, the commune was an organizational form that was intended to increase agricultural production significantly while requiring fewer agricultural workers. These surplus agricultural workers were then to be shifted to industry. Nearly 30 million new workers were absorbed into the urban governmentowned factories in 1958 alone, with millions more taken out of agriculture to work in rural factories. Mao believed that this organizational change alone, without increased state investment spending, would be capable of increasing industrial production while also increasing agricultural production enough to feed the population and provide the raw materials needed by industry. In industry, the Great Leap Forward is associated with the development of small scale rural industries using labor and other resources from the rural areas. Most famous are the “backyard steel furnaces”, which involved at least 60 million people. Another 100 million people were involved in irrigation projects. Others were involved in fertilizer plants, machine shops, cement production, food processing, and so forth. The people were mobilized along semi-military lines to participate in the campaign. Through using the large population in China, highly mobilized, Mao thought that a large increase in agricultural and industrial production could be achieved in a short time. The Great Leap Forward was a great failure. The communes were poorly managed and encountered considerable peasant resistance. Incentives to produce had been destroyed. Workers were pushed to work overtime seven days a week. With 30 million workers withdrawn from agriculture, grain production fell considerably in 1959 and 1960, generating a severe famine, especially in the rural areas of China. It is estimated that by the end of 1961, there had been excess deaths totaling 25 to 30 million people and that some 30 million births had been postponed because of malnutrition. The industrial goods produced were often of such poor quality that they were unusable. And the push for industrialization led to problems in finding sufficient transportation, fuel, and raw materials. Often grain was left to rot because transportation was not available while millions were dying of hunger. In the late 1950s, China also experienced a political rift with the Soviet-Union. In 1960, the Soviet Union withdrew its advisors; this meant that many of the 156 projects that the Soviet Union had started were not completed because China did not have the expertise to do so. 4 (3) 1961-1978 The failure of the Great Leap Forward and the split with the Soviet Union reduced the influence of Mao. At this time, the “pragmatists”, led by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, became major influences on Chinese policy-making. These pragmatists believed that economic development was more important than political considerations at this early stage of China’s development. They believed that, with the elimination of the capitalist and rich peasant classes, the class struggle in China was over. They thought that industrial growth and efficiency through modern technology and modern management were the goals that China ought to be pursuing. To achieve these goals, the “pragmatists” relied heavily on material incentives. In the early 1960s, profits became more important incentives for enterprise directors in industry and wage bonuses became more important incentives for workers. (It should be stressed that, in this period, profits and bonuses were still of secondary importance. The point is that they were more important than they had been.) In agriculture, there was a significant decentralization of decision-making from the commune to lower levels of government. Private plots were restored as were free markets for some farm production. The government agreed to spend more on agriculture and agricultural-related industries. About 20 million workers were sent back to work in agriculture. The details of these changes will be given in Chapter 17. From 1961 to 1965, industrial production almost doubled while agricultural production rose almost 50%. In 1966, Mao strove to reassert his authority by a campaign to “eliminate revisionism”. Thus began the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. In part, the Cultural Revolution can be seen as a pure power struggle. In part, it can be seen as an idealistic attempt to avoid the emergence of a bureaucratic elite of high government officials, as had occurred in the Soviet Union. The Cultural Revolution once again illustrates the importance of ideology to Mao. Purges occurred on a large scale (from 1966 to 1969, 68% of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, 73% of the Politboro, and 86% of the first secretaries of the provinces were purged or at least severely humiliated. Many of these people would later emerge as the leaders of the reform period. More than 200,000 intellectuals were persecuted.) The goal espoused by Mao was “spontaneous development” --- socialism was to be created simultaneously with the creation of a developed country. Many of the policies of the Great Leap Forward were resurrected, including emphasis on moral incentives, an elimination of the traditional enterprise manager in factories, emphasis on small-scale factories, “resettlement” of millions of people into rural areas, and so forth. The role of profits and bonuses as incentives was ended. In fact, wages were basically frozen through most of the latter 1960s. Even promotion by seniority was not allowed. In agriculture, the system of payment to commune members was changed in favor of the Dazhai system. Under the Dazhai system, the peasants would sit in judgment of each other at periodic team meetings to determine what each peasant’s work was worth. The idea was to use social pressure to induce people to work hard. (If you wish to understand the idea of “moral incentives”, think of the change in work and other behaviors that occurs when people feel that their country has been attacked by an enemy. Mao thought he could maintain this attitude continually.) 5 In the companies, revolutionary committees took-over the functions previously performed by the enterprise director. In both the communes and the factories, there was widespread politicization dominated by a “personality cult” of Mao. Between 1965 and 1967, over 100 million copies of the Selected Works of Mao Zedong were printed. Peasants and workers were judged largely by their “political correctness” in relation to Mao’s thought. During the late 1960s, educational opportunity was not based on performance in school. All high school students had to work for two years after graduation; some might then be nominated for college by their enterprise or commune. College curriculum focused on practical work. For about three years, most universities were closed. Scientists and intellectuals were denigrated; “red” was much more important than “expert”. The period of the late 1960s was one of widespread unrest. Various factions fought (often with each claiming itself as the only one true to Mao’s thought). Millions of paramilitary troops, organized as Red Guards, caused widespread disruption. Worker absenteeism was high. Decisions came to be made by very few people, as workers became afraid to say anything that might be construed as negative. (Merely being accused of being a “capitalist-roader” could be extremely harmful,). With this disruption, it is hardly surprising that GDP fell at an annual rate of 2.5% from 1966 to 1968 and that industrial production fell much more. The Cultural Revolution was a period in which there was no stable framework of law. Rule was often by arbitrary whim, enforced by the Red Guards. Hundreds of thousands of people died; millions suffered from injustice. The legacy of the Cultural Revolution is important in understanding-the direction that China has been taking in the reform period. In 1965, with the American escalation in Vietnam, the recent split with the Soviet Union, and the weakness caused by the failure of the Great Leap Forward, China felt militarily threatened. From 1965 to 1971, China tried to develop a “Third Front”. The Third Front was a massive construction project to create an entire industrial system in remote sites in the interior of China. There it was believed that the project would be secure from foreign invasion and would be available to allow China to mount an effective resistance. The project was large, hastily prepared, and very inefficient. One estimate as of the late 1980s is that “China’s annual industrial output was 10-15% below what it would have been if the Third Front had never been undertaken”. Many of the excesses of the Cultural Revolution were ended by 1970. In the early part of the 1970s, the pragmatists regained control of most of the government administration. Material incentives were re-established. Central planning was re-instituted with even greater decentralization to lower levels of government. Relations with the United States were opened in 1972 with the visit of President Nixon. This led to a greater openness to trade and to the importation of Western equipment and technology. However, the control of the pragmatists was not complete; the radical leftists, led by the so-called “Gang of Four”, had a certain amount of control as well. With the aging of its leaders, especially Mao, China was about to embark on a major struggle for power. The Maoist model of economic development had differed somewhat from the model practiced in the Soviet Union. Five key differences have been noted. First, the economy of China had been militarized. Much production was organized along military lines. 6 And the military had first priority on resources. Second, the Chinese economy had been more decentralized than the Soviet economy. Small businesses had been encouraged. Third, China practiced regional as well as national autarky. Not only did China avoid international trade as much as it could, but also its regions were expected to be self sufficient and not trade with each other. Fourth, for much of the socialist period, there was an absence of material incentives. And fifth, labor mobility had been completely restricted. When Mao died in 1976, evaluation was made of the economic results of his leadership. Some results were very positive. GDP per capita had approximately doubled since 1952, investment rates (the buying of capital goods) were high, literacy rates had increased to 65%, and life expectancy had risen to 64, which is very high given the country’s standard of living. But most of the evaluation was negative. Unemployment and underemployment were considerable. Of the 191 million person increase in the labor force between 1952 and 1978, only 37% had been absorbed into industry or services. The rest had remained in agriculture where they were seriously under-employed. Both rural and urban incomes had been virtually stagnant since the mid-1960s. (However, there was a large gap between urban incomes and rural incomes.) The population was very poorly housed. Indeed, consumption of all kinds (especially in services) had been neglected and there were shortages of all kinds of consumer goods. The problem of rapid population growth had not been solved. And the technological level of China was 10 to 20 years behind the West; perhaps 60% of China’s capital was technologically obsolete by Western standards. Efficiency and productivity were very low. The country had suffered from the great instability in policy making; the period from 1949 to 1978 had seen five great surges in investment spending followed by periods of much slower growth (or even a decrease) in investment spending. Following the death of Mao, leadership passed to Hua Guofeng. He had the “Gang of Four” arrested, “rehabilitated” Deng Xiaoping, and began a systematic campaign to destroy the influence of Mao. From 1978 until his death in February of 1997, Deng Xiaoping was the most important leader in Chinese politics. The return to power of the “pragmatists” meant a return to the goal of economic development and a reduction in the importance of ideology. The Four Modernizations Program, which called-for the development of agriculture, industry, science and technology, and defense, was stated in 1976. By 1978, a period of substantial reform had begun. (4) The Reform Period: 1978 to the Present The recent reform period began in 1978. The details of the reforms will be discussed in later chapters. The reform period has been noted for the limited importance of any ideological considerations. The goal has been economic development and the leadership has embraced whatever means it believed were necessary to achieve that end. As you will see in later sections, this has meant an expansion of markets, an expansion of production from companies not owned by the central government, and an opening to the global economy that would have been unthinkable prior to 1978. By the mid-1990s, China had moved away from being a command economy and had become basically a market economy. 7 China’s strategy of reform was on of gradualism, in contrast to the reforms of Russia and Eastern Europe. Despite never using “shock therapy”, over a twenty year period, China basically dismantled all of the institutions of the command economy. The earliest aspect of this reform period was the restructuring of the agricultural economy and the elimination of the communes. In the reform period, agriculture was greatly changed by the introduction of the household responsibility system and the growth of township and village enterprises, as will be described in Chapter 17. It was the success of the reforms of agriculture that generated further economic reforms (agricultural production increased by 1/3 between 1978 and 1984 despite there being fewer work days in farming). A second aspect of the reforms was a change in the planning system. At first, central planning was greatly reduced in importance. In this period, he plan targets were frozen. Any increase in production could be sold for higher market prices outside of the plan. As the economy grew, the plan targets became less and less significant and China “grew out of the plan”. By 1993, central planning had been phased out completely. A third important aspect of the reform period was the dramatic enlargement of the importance of markets. Consistent with the growing importance of markets, there were major changes in the types of enterprises. In Chapter 18, we will discuss the growth of rural industry (called township and village enterprises), some important changes in the organization of urban state-owned (i.e., government owned) enterprises, the growth of urban collectives (companies owned by their workers), and the growth of privately-owned companies. Throughout the reform period, there were a large number of new start-up companies. These new companies enhanced market competition. Prices were gradually decontrolled and came to reflect the forces of demand and supply. Enterprises became more and more focused on profits instead of fulfilling the plan targets. A fourth important aspect of the reform period was the decentralization of decision-making. Enterprises, local governments, and peasant households now have much more decision-making power than they did prior to 1978. Personal savings have increased and banks gradually have replaced the government as the source of funds for business investment spending. Beginning in 1995, however, there was some recentralization of decision-making that came with the creation of a modern tax collection system. And a fifth important aspect of the reform period has been an enormous increase in Chinese integration into the global economy. This began with the creation of Special Economic Zones and then culminated in China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. Indeed, China made many more concessions than other countries had to make in order to be admitted to the World Trade Organization. This entrance into the global economy will be discussed in detail in Chapter 19. As we will see, China’s reforms were very different from those of the former Soviet Union or the Eastern European countries. They also seemed to go against the prescription for reform made by most Western economists. The reforms actually can be categorized into two periods. From 1978 to the early 1990s, no social group suffered any significant economic loss as a result of the reforms. This period has been labeled as a period of “reform without losers”. Even those who worked in the state-owned enterprises were protected. This ability to prevent “losers” meant that the economic reforms were widely supported by the population. The second period began in 1993. In this period, China began to create a modern tax system. China restructured its banking system with its central bank, the People’s Bank of China, coming to resemble the American Federal Reserve System and with its commercial banks cut off from government subsidies. And China revised its company law so that all state-owned companies were transformed into 8 corporations with shares listed on newly-formed stock markets. Along with other changes we will discuss, employment in state-owned enterprises declined 40%. Profits of state-owned enterprises declined greatly (due to increased competition from other kinds of enterprises). In the mid-1990s, many township and village enterprises, collectives, and state-owned enterprises were privatized (usually bought by the management). By 2004, nearly twice as many urban workers worked for private enterprises than worked for state-owned enterprises. Finally, as noted above, China acceded to the World Trade Organization in 2001. This second period of reform was definitely a period of “reform with losers”, especially those who worked in the state-owned enterprises. Overall, as we will see in Chapter 20, the Chinese reforms seem to have been successful, although there are still important areas where improvement is needed. The growth of GDP per capita in China averaged an astonishing 8.5% per year between 1978 and 2005. No other country has ever achieved growth rates of GDP per capita that high for such a long period of time. But the benefits of the reforms have not been equally shared across the population. Since there have been disagreements within the leadership ever since the beginning of Communist China in 1949, it should not be surprising that these reforms have generated great controversy within China. Those now called “conservatives” desired a return to the pre-reform policies. Many of these people were government officials at various levels whose power and prestige was threatened by the reforms. One of the compelling points about the nature of the early economic reforms in China is that, as we saw, they were created so that there would be no “losers” from them, as we will see. As a result, the reformers were able to overcome the opposition from the “conservatives” that typically accompanies any kind of significant reform. The debate was thus framed between the “moderate reformers” and the “radical reformers”. The moderate reformers based their proposals on Deng’s four cardinal principles: commitment to Marxism-Leninism and Maoism, leadership by the Communist Party, socialism, and the maintenance of the existing state structure. They saw reform as a slow process, taking perhaps 30 years. They desired to maintain central planning as the heart of the economy. They did not see labor or land as commodities to be exchanged on a market, and therefore they opposed the creation of true labor or land markets. They wished to maintain strict government control over investment spending (buying capital goods) and over all foreign exchange. They were very opposed to political pluralism. And they were concerned by the rise in “spiritual pollution” (crime, corruption, materialism, and so forth) that they thought would likely accompany the creation of a market system. As you can see, China’s reforms did not follow the ideas of the moderate reformers except for the opposition to political pluralism. On the other hand, the radical reformers favored a much greater role for the market, with the plan to be secondary. They favored the development of true markets for labor, natural resources, and capital goods. They saw reform as occurring relatively rapidly. And they favored political pluralism and a greater move toward democracy. While the actual course of reform has been less than the radical reformers desired, they certainly have been the major influence on the economic reforms, especially in the 1990s. However, political reform has not occurred at all in China. In 2003, Hu Jintao became Party leader and therefore the leader of the 9 Chinese government. Wen Jiabao became Premier. With their leadership, there seems to have been no change in the direction of Chinese reform policy.