Lecture Notes for Week 2.

advertisement

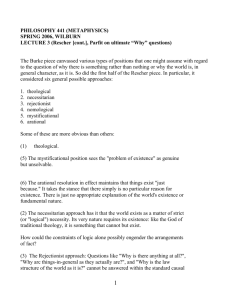

PHILOSOPHY 441 (METAPHYSICS) SPRING 2006, WILBURN LECTURE 2 (Burke, Rescher on ultimate “Why” questions) Summary of last time? What I like about this book? Part I: Existence What is Burke’s and Rescher’s concern when they talk about existence? Start with some points of clarification from the Burke piece. What is the issue, what might an answer to it look like. Then we’ll turn to Rescher and look a specific more developed account. Burke’s qualifiers to help us understand the questions: (1) Why is this a question about the existence of “concrete objects” rather than abstract objects? (2) Why does Burke say this: When we ask “Why is there something rather than nothing” we necessarily use “is” in tenseless way? Why don’t we just mean, “Why is there something now rather than nothing?” (3) Why does Burke say this: When we ask "why" there is something rather than nothing, we are asking for a reason, but not for any particular kind of reason? So, that’s how Burke qualifies the question. Let’s canvass some possible types of answers to see what’s been suggested historically before we go onto Rescher. (1) Leibniz’ Theistic Response involving necessity and contingency. What is it? What’s your reaction to it? Rescer cites Kant in the next article: “To have recourse to God as the Creator of all things in explaining the arrangements of nature and their changes is at any rate not a scientific explanation, but a complete confession that one has come to the end of his philosophy, since he 1 is compelled to assume something [supernatural]. . . . to account for something he sees before his very eyes.” (2) “Hume-Edwards Response regarding the nature of complete explanation. What is it? What’s your reaction to it? Seems to leave the following concern unanswered: “Given that matter is conserved, matter exists at all times if it exists at any. But why does it exist at any?” And Rescher has a response to it in the next article. Remember when he talks about team members showing up for a game? What does he say? Each member of the team is present because he was invited. Does that explain why the team is present as a whole. . . Even when we have resolved the former issue, a genuine explanatory question still remains. “When we ask an explanatory question about a whole, we don't just want to know about it as acollection of parts, but want to know about it holistically qua whole. When we know why each particular day was rain-free (there were no rain clouds about at that point) we still have not explained the occurrence of a drought. Here we need something deeper—something that accounts for the entire Gestalt.” (3) Quantum Cosmological Response: What is it? What’s your reaction to it? “The universe began with an uncaused quantum change, from nothingness to a cosmos, consisting of a tiny volume of space which then expanded.” Here we don’t need a lot of the details. The explanation, for instance, of why the expansion occurred. I don’t want to gas about “false vacuums” as though I know what I’m talking about. The only pertinent point is this: The laws of quantum physics provide for spontaneous transitions within all physical systems. Extrapolating, it is reasonable to suggest that the same laws provide for spontaneous transitions within nothingness, which means transitions from nothing to something. 2 Underlying idea here as to why this might be OK is that mathematically, nothing really changes because the overall energy value of the system is zero -- expansive energy is completely balanced out by contractive gravitational energy. You don’t want to dismiss it as too speculative. There’s a lot speaking for it. Historically, a lot of philosophical questions have only become intelligible in the past because they were rephrased as scientific questions. Maybe this is one of them. (1) Quantum physics offers the only prospect we have for a naturalistic explanation of the why question because it countenances untriggered events. (2) It also countenances the spontaneous coming into being of entities—for example, the appearance (followed generally by the quick disappearance) of particles within very strong electromagnetic fields (this has actually been observed). So you might think this: The appearance of a universe out of nothing is no stranger than other events which have already been countenanced by quantum physicists. What are the possible limitations of this? They have to do with the notion of a natural law. It requires that certain conditions be met by natural laws. That laws be objective, mind-independent features of reality that can be understood in terms that are prior to reality. So, if you think that natural laws are relations among properties you have problems. If you think that laws of nature originated with nature, you’ve got problems. Quantum laws are formulated statistically, which invokes time. So if you think that time is a feature of the world that came into existence with the world, you’ve got problems. So, this is just an initial canvassing. But it gives us an idea of the sort of thing that we are looking for. What the problem is. What a solution to it might look like. 3 Let’s now turn to Rescher (“On Explaining Existence”) for a more focused treatment. Rescher starts with his own taxonomy of different types of approaches to the question. And this we can run down pretty quickly: He says there are six broadly different kinds of approaches, some of which we’ve looked at: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) theological necessitarian rejectionist nomological mystificational acausal Let’s start by looking at each of them, and not in this order. THE MYSTIFICATIONAL APPROACH: What is the central idea here? Do mystificationists deny that this is an intelligible question or that there is an answer to it? (Colin McGinn) So, what do you think of the mystificational approach? 4. THE ARATIONAL APPROACH: What is it? How is this different from the mystificational approach? Maintains that things exist "just because." It takes the stance that there simply is no particular reason for existence. Let’s give this a chance. It may not be completely stupid. I guess it asks “why should we suppose that the existence of the universe requires a reason? Why suppose that the default state of things is non-existence, so that existence rather than non-existence is the thing that requires explanation? 4 That seems like a legitimate question. Rescher cites a debate between Bertrand Russell and Fred Copleston on arguments from first cause: “I can illustrate what seems to me your fallacy. Every man who exists has a mother. And it seems to me that your argument is that therefore the human race must have a mother. But obviously the human race hasn't a mother— that's a different logical sphere." What’s Rescher’s response to this? Analogy: The causes of homo sapiens as a species may not be of the same particular type as the cause of a particular person. But that doesn’t mean that we cannot provide an account of the latter in terms of evolutionary biology. 5. THE THEOLOGICAL APPROACH: This we’ve already looked at and we’ve described Rescher’s sentiments. 6. THE NECESSITARIAN APPROACH: What is it? What do you think of it? The real problem here is this: How could the constraints of logic alone possibly engender the arrangements of fact? 7. THE REJECTIONIST APPROACH: What is it? What do you think of it? One example from Kant’s antinomies: It is illegitimate to try to account for the phenomenal universe as a whole. Explanation on this view is inherently partitive: phenomena can only be accounted for in terms of other phenomena, so that it is in principle improper to ask for an account of phenomena-as-a-whole. The very idea of an explanatory science of nature-as-a-whole is illegitimate. Why does Rescher think this objection is problematic? It is in the course of responding to the rejectionist account that Rescher sets 5 out to give his positive account. How does he do this? What does he think is Henpel’s mistake in the following passage: “Why is there anything at all rather than nothing? .. . But what kind of an answer could be appropriate? What seems to be wanted is an explanatory account which does not assume the existence of something or other. But such an account, I would submit, is a logical impossibility. For generally, the question "Why is it the case that A?" is answered by "Because B is the case" . . . [Am answer to our riddle which made no assumptions about the existence of anything cannot possibly provide adequate grounds. . . . The riddle has been constructed in a manner that makes an answer logically impossible. . . .” What does Rescher mean when he says that this objection fails to distinguish appropriately between the existence of things on the one hand and the obtaining of facts on the other, and supplementarily also between specifically substantival facts regarding existing things, and nonsubstantival facts regarding states of affairs that are not dependent on the operation of preexisting things. He thinks our prejudice here is a presupposition that things can only originate from things,that nothing can come from nothing (ex nihilo nihil fit) in the sense that no thing can emerge from a thingless condition." Leibniz:[T]he sufficient reason [of contingent existence] .. . must be outside this series of contingent things, and must reside in a substance which is the cause of this series.” Rescher calls this the principle of genetic homogeneity. Made disreputable by modern science. Matter can come from energy, and living organisms from complexes of inorganic molecules. If the principle fails with matter and life, need it hold for substance as such? 6