We thank all the surgeons, nephrologists, and

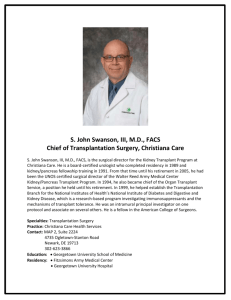

advertisement

Title Priority setting in kidney transplantation in Sweden Authors Faisal Omar: Department of Medical and Health Sciences Linköping University, Sweden E-mail: faisal.omar@liu.se Per Carlsson: Centre for Medical Technology Assessment, National Centre for Priority Setting in Healthcare, Linköping University Email: per.carlsson@liu.se Marie Omnell Persson: Department of Nephrology and Transplantation, Skåne University Hospital (Malmö), Lund University, Malmö, Sweden E-mail: Marie.Omnell-Persson@med.lu.se Stellan Welin: Department of Medical and Health Sciences Linköping University, Sweden E-mail: stellan.Welin@liu.se Correspondence: Marie Omnell Persson: Department of Nephrology and Transplantation, Skåne University Hospital (Malmö), Lund University, Malmö, Sweden E-mail: Marie.Omnell-Persson@med.lu.se 1 ABSTRACT Background: Kidney transplantation is the established treatment of choice for end-stage renal disease; it increases survival, and quality of life, while being more cost effective than dialysis. It is, however, limited by the scarcity of kidneys. The aim of this paper was to investigate the fairness of the priority setting process underpinning Swedish kidney transplantation in reference to the accountability for reasonableness framework. To achieve this, two significant stages of the process influencing access to transplantation were examined: (1) assessment for transplant candidacy, and (2) allocation of kidneys from deceased donors. Methods: Semi-structured interviews were the main source of data collection. Fifteen Interviewees included transplant surgeons, nephrologists, and transplant coordinators representing transplant centers nationwide. Thematic analysis was used to analyze interviews, with the Accountability for reasonableness serving as an analytical lens. Results and Discussion: Decision-making both in assessment and allocation are based on clusters of factors that belong to one of three levels: patient, professional, and the institutional levels. The factors appeal to values such as maximization of benefit, favoring the worst off, and equal treatment, which are traded off. Conclusions: The factors described in this paper and the values on which they rest on the most part satisfy the relevance condition of the framework. There are however potential sources for unequal treatment which we have identified. These are clinical judgment and institutional policies relating both to assessment and allocation. The appeals and revisions mechanisms are well developed. However, there is room for improvement in the areas of publicity and enforcement. The development of explicit national guidelines for assessing transplant candidacy and the creation of a central kidney allocation system would contribute to better publicity and enforcement. The benefits of these policy proposals in the Swedish transplant system should be studied further. 2 1. IINTRODUCTION End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is a condition in which kidney function decreases significantly and permanently requiring renal replacement therapy. Kidney transplantation is the established treatment of choice; it improves survival rates and offers higher quality of life compared with dialysis [1,2]; furthermore, it is significantly more cost-effective [3]. Despite these advantages, the availability of transplantation to all who can benefit from it is limited by the scarcity of kidneys. In 2009, less than half of Swedish patients on the kidney transplant list had access to a deceased donor kidney. ESRD patients in Sweden are treated in one 65 nephrology clinics, 90% hospital bases, which refer transplant candidates to one of four transplant programs [4]. Each program manages independent waiting lists both in terms of accepting patients to the transplant list as well as allocating organs: Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Göteborg, Huddinge University Hospital in Stockholm, Skåne University Hospital in Malmö, and Uppsala University Hospital. Scandiatransplant, a Nordic network, facilitates a limited number of organs exchanged between centers (approx. 12%) [5]. Given the existing resource constraints, transplant programs naturally employ various criteria to prioritize among potential recipients as a means of rationing the limited pool of kidneys. Considering the decentralised nature of Swedish healthcare and in the absence of national guidelines either for assessing eligibility for transplantation or the allocation of kidneys, important questions arise regarding the fairness of the priority setting process determining access to transplantation. The aim of this study was to investigate the fairness of the priority setting process underpinning Swedish kidney transplantation in reference to the Accountability for Reasonableness framework [6]. Two stages with significant influence on access to transplantation were examined: (1) assessment for transplant candidacy, and (2) allocation of deceased donor kidneys once patients are on the waiting list. This is the first empirical study to specifically examine the unique aspects related to priority setting in kidney transplantation using the A4R framework. To achieve our aims and create and accessible structure, the paper is divided into a number of sections. We first introduce the A4R framework and methodological details of the study. Next we elucidate the priority setting process in Swedish kidney transplantation covering both aspects of assessment and allocation. This account is important for two reasons. First this priority setting process has never been described before; secondly this description is necessary for carrying out a purposeful evaluation of the process in reference to the A4R. We next present factors 3 and values which emerged as playing a role in priority setting decisions. This is followed by an evaluation of the fairness of the overall priority setting process (including factors and values) in reference to the conditions of the A4R. Finally we address the limitation, implications and provide concluding remarks. Accountability for Reasonableness The A4R priority setting framework has received increased attention over the past decade, becoming a prominent paradigm in health policy. It has been employed in empirical studies examining priority setting at different decision-making levels, in various countries, and within different medical specialties [7-11]. The framework emphasizes the establishment of a fair and legitimate priority setting process rather than relying on overarching substantive principles. Traditional methods appealing to comprehensive philosophical approaches such as utilitarianism and egalitarianism, it is argued, take as their starting point different values that lead us to different decisions, none of which can be claimed to be completely correct[9, 12]. The framework stipulates four conditions which contribute to the fairness of priority setting processes [6, 12]. The hope is that if we agree on the fairness of the process, we are more likely to agree on decision outcomes also. Figure 2. The conditions of the A4R framework [6, 12] While procedural fairness in the allocation of scarce medical resources is vital, it cannot be dismissed that “substantive, morally relevant values and principles are indispensable for just allocation” [13]. In line with this observation, the framework has been criticized on the grounds of the diminished role it assigns to substantive values that underlie priority setting processes, even if there is no unanimous agreement on such values [14-16]. It is argued that being explicit about the substantive principles fosters legitimacy for the decisions reached. It has also been criticized for limiting the range of stakeholders included into the priority setting process [17, 18]. Despite the criticism, there remain valuable contributions regarding procedural fairness that the application of the A4R can make. Our approach will be to use the framework’s strengths as a tool for examining issues related to procedural fairness while also highlighting the substantive values found in the priority setting process. 4 2. METHODS Data collection and analysis During the design phase different methodological options were considered. A survey based study had the benefit of being less time intensive since the study sites are spread across a vast geographical area; additionally it would eliminate the logistic challenge of arranging interviews with busy professionals who are often on call. Despite the benefits of a survey study, it was agreed a qualitative interview based study would be more suitable to understanding the underlying factors contributing to priority setting decisions. It better acknowledges the importance of the social worlds that the events take place, which can be lost when conducting a survey study [19]. Visiting the environments where decision making occurs, and meeting the decision makers in person for in-depth interviews would provide a nuanced understanding of the context in which priorities are set, helping to generate a richer data set. Further it would allow probing interesting topics during interviews which wouldn’t be possible with a survey. For these reasons interviews were chosen as the approach for data collection. A semi-structured interview guide was developed, which was broadly based to provide a complete depiction of the priority setting processes in Swedish kidney transplantation. The guide also addressed topics related to the conditions of the A4R framework. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The method chosen for analyzing the interviews was thematic analysis. Grounded theory, while considered, was ruled out for two reasons. Primarily because the object of the study was not theory generation, in which case grounded theory would be more appropriate. The central role of the A4R in the study required a flexible method to allow bringing in an external framework which would have been more difficult with grounded theory. Thematic analysis is a more flexible approach which facilitates the identification and extraction of emerging themes which are particularly significant for the research questions and aims [20]. In the present study it would better allow us to use the A4R as an analytical lens through which relevant themes within the data could be extracted, analyzed and discussed. 5 Study Sites We investigated priority setting at all centers performing kidney transplantation in Sweden. In addition, a selection of satellite nephrology clinics that refer patients to the centers was included. This was done to gain a comprehensive representation of the referral process from the point of view of both the transplant centres and the referring nephrology units. Centers were sampled for representativeness. Subjects In total, 15 professionals were interviewed for this study. This included 6 surgeons, 7 nephrologists, and 2 transplant coordinators. At least one surgeon was included from each of the transplant centres. The 7 nephrologists were from nephrology clinics located in different regions of the country representing the 4 transplant regions. Finally, a recipient transplant coordinator and a donor transplant coordinator were also included. Gender distribution was almost equal, with 8 male and 7 female interviewees. The sampling techniques purposefully included the key decision-makers at transplant center and nephrology units. The majority of respondents were senior physicians and surgeons with an average of over 20 years of experience in this field. A number of the interviewees were either actively involved in or had had previous administrative responsibilities within their departments. This was a critical component of the study, since these responsibilities often require engagement in priority setting issues, which results in a deeper understanding of the way that resource scarcity affects priority setting at the clinical and departmental levels. 6 3. RESULTS There are three goals in this section. First we will describe the priority setting process as it relates both the assessment for transplantation and allocation of deceased donor kidneys. Next we provide an overview of the factors which emerged as having an impact on priority setting decisions within both stages. Finally we highlight the values which underpin the priority setting process in relation to the decision making factors identified. The full list covering both factors and values is presented in Table 1. The priority setting process Transplant centers provide regional nephrology clinics with a list of medical investigations required for all referents. The final decision regarding eligibility lies with the transplant center. While investigations are more or less similar across centers, there are procedural differences in how listing decisions are reached. Two centers hold “gatekeeper” meetings where patient cases are discussed and a group consensus reached, the group shares responsibility for all decisions. The remaining two centers do not require such meetings; however decisions are shared during daily rounds; only for particularly difficult cases are group consensus sought. As well as being an opportunity to disseminate information about decisions, gatekeeper meetings and daily rounds encourage consistency between professionals within the centers by publicizing the decisions made and their rationales. Once listing decisions are reached, some centers meet all patients personally to relay the decisions, while others meet only some patients and communicate via the referring nephrologist to others. The publicity and documentation of rationales underlying kidney allocation decisions differed between centers. One centre has a long established documentation and rationalization procedure for each kidney allocated, requiring the responsible surgeon to justify the allocation of a kidney to a particular patient on the waiting list compared to alternative wait-listed patients. A second center has initiated similar procedures; this was viewed positively by the centers as a mechanism to increase transparency and accountability by tracking allocation decisions. The remaining centres did not indicate having any systematic mechanism to document the rationales for the allocation decisions. Second opinion mechanisms, after a denial for listing, are well developed and supported nationally. This is the primary means of appeal in the system. However, before such a stage there are opportunities within the centers to have decisions reconsidered, if for example the patients status changes. For practical reasons, allocation decisions cannot be appealed in the same way denial of admission to the 7 waiting list can. Once a kidney has been allocated, the decision cannot be reversed. Patients do not generally have any knowledge of the kidneys that have become available or whether or not they were being considered for such a kidney, since this information is limited to the transplant centres. However the general criteria used in the allocation process (if they are seen as unfair) may be contested during meetings which occur at regular intervals between the kidney foundation and the transplant programs. There are no regulatory bodies responsible for monitoring kidney transplant procedures or outcomes in a systemic way across centers as a result of Sweden’s decentralized health care structure. Second opinions do however serve as an informal regulatory mechanism between the centers, since it would be peculiar to have too divergent an opinion between centers serving patients in the same country. Nonetheless procedures do differ and the centers are on the most part self-regulating. Factors affecting priority setting decisions Throughout the interviews, respondents raised various factors they consider when making decision at both the listing and allocation stages. Themes that arose frequently were identified as stand-alone factors such as cardiovascular status or waiting time. Themes such as alcohol dependence and psychological problems required being identified as belonging to a particular factor such as ‘compliancerelated factors’. The emergent factors were further grouped into more general categories that connected them, such as ‘patient-level’, ‘professional-level ’, or ‘institutional-level’. In a single patient case a cluster of factors from the different levels influence decisions simultaneously. This is true both for listing and allocation decisions. We will in this section highlight a number of these factors; for a full overview of the factors and the categories they fall under, see Table 1. Patient level The largest share of factors falls under the patient level. This is because whether transplantation as a treatment is indicated depends on multiple patient specific factors which can be clinical, life style, or quality of life based. Furthermore in the allocation stage the available organs are matched on multiple levels to an individual patient to bring about the best post-operative results. While some factors at the patient level are easily labeled as predominantly clinical, life style, or quality of life based others have aspects appealing to more than one category at the same time. We will use some examples to illustrate. 8 Cardiovascular status and malignancies (listing stage), HLA compatibility and blood group (allocation stage) are prominent clinically based patient level factors. On the other hand compliance-related factors are related to life style choices and include issues such as continued alcohol abuse. These life style factors are not considered as moral judgment against the patient, but rather because they have a direct impact on graft survival if the patient continues engaging in these behaviors. Patient-specific risk benefit considerations is an example of a quality of life based patient level factor. For instance, a patient who is deeply unhappy with dialysis has more to gain from a transplant and is permitted to take a greater risk to undergo transplantation. Conversely, a patient who is doing relatively well on dialysis physiologically and psychologically and enjoys the social aspect of coming to hospital for dialysis treatment does not have as much to gain. In such cases, carrying out a transplant that can result in severe complications can have detrimental effects on the patient. Obesity plays a central role in decision-making for transplantation; however, the precise cut-off for this is not clearly stipulated and can differ somewhat between centers with some centers having clear BMI cutoffs. What is clear is that extreme obesity is generally considered a contraindication. More significant is a patient’s overall fitness which is an important factor indicating how well a patient will cope with transplantation. It is clear that this overall fitness is more than a simple measurement of BMI, and is rather patient-specific. The following quotation captures how consideration of overall fitness and obesity manifest in the clinical setting and influence the assessment for transplantation. At the same time, it captures the significant role of clinical judgment: “I have had patients where it says (on their medical record) they have had a stroke, they have had an infarction, they have had a coronary by-pass, and in walks a tanned man, back from playing an 18-hole game of golf, who works in his garden every day. Or in comes a patient on a wheelchair who is 20 kilos overweight, mainly on the belly, and steps out of the wheelchair because I have to look at him; he lies down on the bed in the room as I have to palpate his belly, and he can hardly get his trousers off“ (surgeon). Obesity is an example of a patient level factor which has aspects that are clearly clinical and others which are life style based. Furthermore it includes aspects which bridge over to the professional (clinical judgment), and institutional levels factors (BMI cut off). It aptly demonstrates the complexity of the priority setting process in kidney transplantation. 9 Professional level Clinical judgment plays a significant role in priority setting and was considered particularly important in borderline cases where it can tip the balance regarding the final decisions: “Most cases are not borderline cases, but there will always be borderline cases in medicine, and because of that I think that whether or not we have the same criteria, it really does not matter—there will always be personal opinions…….You should not make an important judgment on just a hunch or a feeling; you should also look at the data, but then you should try to make it all come together in the end. Sometimes this feeling or hunch is the factor that makes you say yes or no, if you are on the line. Then you have to use your clinical judgment; this is your job, this is what you are paid for” With no central (algorithm based) allocation system in Sweden, such as that employed at UNOS [21], each surgeon on duty must decide on how to weigh the various factors in every single allocation decision. This depends heavily on the surgeon’s interpretation of the factors that are seen as relevant further cementing clinical judgment’s central role in the priority setting process. Clinical judgment is often an implicit decision making tool. It is according to our analysis a potential source of unequal treatment between patients. As indicated in the quote above professionals believe that this is an inevitable part of medical practice. Second opinions do play a role in restraining the impact of differences in opinion as a potential source of unequal treatment. There is however no guarantee that patient will seek second opinions. Clinical judgment has clear implications on the fairness of the process. This will be discussed further (in reference to the A4R) in the evaluations section which will follow. Professional consideration of resource scarcity is another professional level factor which emerged as having a clear influence on decision-making: “We have this shortage of kidneys. We must not waste kidneys on poor cases; you have to have a certain degree of certainty that this will be successful. If it is not, if the patient is too old or too sick or whatever, there is no use in accepting him” The symbolism of gatekeeping in this context portrays the role of centers, and decision makers, as guardians of society’s resources (deceased donor kidneys) which mustn’t be squandered. The allocation process similarly builds on the concept of gatekeeping. In the absence of explicit national allocation system, decisions fall to the surgeon (gatekeeper) on duty at each center in cooperation with an immunologist to determine the best fit allocation of a kidney. 10 Institutional level Difference in policy between centers is an important part of institutional level factors. An example is policies regarding obesity and BMI cut-offs, which can lead to different decisions for similar patients between centers: “I know the data on obesity are contradictory, and we are very strict about that here… We are somewhat stricter ( than other centers) perhaps” (surgeon) Similar to clinical judgment, institutional policies can be a source of unequal treatment, leading to different decision outcomes. As a result of where a patient resides, and which transplant center they are referred to their chances of being accepted to the transplant list can differ. As mentioned in the above quote this is in part because evidence regarding obesity is contradictory on this subject it is an area where reasonable disagreement could be expected; we will return to the implications this has on fairness in the evaluation section to follow. Another institutional-level factor is the marginal donor program at one of the centers; with a separate waiting list for patients who accept kidneys from donors defined as marginal donors or extended-criteria donors. This list is only used when kidneys from marginal donors are available. The patient remains on the ordinary waiting list as well, and still has the same chance as any other patient to get a kidney from a standard-criteria donor. Other centres, while they indicated the use of similar-quality kidneys, do not label them as marginal and prefer to indicate that these kidneys are matched to a suitable recipient 11 Values effecting priority setting decisions Maximizing benefit Maximizing benefit can denote different meanings depending on the desired outcome. One common distinction is saving the most lives vs. saving the most life years. The availability of dialysis as a maintenance treatment contributes to the fact that many of the factors identified in table 1 lean towards the second sense of maximizing benefit (saving most life years). This differentiates kidney transplantation from other areas of organ transplantation such as heart or liver transplantation, where replacement therapies to keep patients alive are not available and receiving a transplant is an urgent matter of life or death. Taking this into account, and in light of the organ shortage and the availability of dialysis, the centers place a greater weight placed on maximizing benefit in terms of most life years. Decision making is also influenced by consideration of maximizing benefit for a particular kidney vs. maximizing benefit for a particular patient. In the first instance, the goal in the centers is to maximize the benefit of the kidney as a scarce medical resource, where decision-makers look to transplant the organ in a patient where its longevity will be maximized. Here it is driven by a responsibility of decisionmakers to act as gatekeepers of society’s resource. On the other hand maximizing benefit for a particular patient, is measured from the point of view of the gains that a particular patient will have from transplantation compared to remaining on dialysis. While factors which appeal to maximizing benefit are found in both stages (malignancies, age, HLA, agematching), it plays a greater role at the allocation stage. Technically speaking, the transplant list can always be expanded to include more patients; however, centers cannot increase the number of kidneys that are available for transplantation at will. It is at the allocation stage that the maximization of benefit becomes pronounced. This maximization of benefit is balanced against considerations of justice for the individual. If maximization of benefit was the only concern, it could mean that older and sick patients would not be transplanted; this is, however, not the case according to our analysis and other values are considered in the decision-making process. 12 Priority to the worst off An example of giving priority to the worst off is illustrated by the consideration given to a patient’s negative experience with dialysis, where the patient’s relative well-being taken as a value input at the assessment stage. At the allocation stage, it is seen when prioritizing those with dialysis access complications, although they may not be the most ideal patients from a pure benefit maximization perspective, compared to another patient. However, without dialysis such patients are in urgent need of transplantation. While age-based prioritization (whether positive or negative) is not allowed in the Swedish health system [22] a preference for younger recipients is defended primarily because they fare badly on dialysis in the long term due to special needs related to growth and development, which cannot be met through dialysis. At the same time, there is an appeal to maximization of benefit since younger patients have gains in quality of life that are higher than for older patients; they will predictably also have a longer graft life, thus making use of the donor kidney to a larger degree. This example illustrates how more than one ethical value can influence an individual priority decision. Equal treatment Treating people equally is most robustly illustrated by the appeal to waiting times as a prioritization tool for allocation. Waiting time is used as an “objective” measure of deservedness for transplantation in a first–come-first-served approach. There is a risk that first-come–first-served can give advantage to those better inform about the benefits of transplantation (often tied to higher socio economic status) [13]. Swedish transplant programs have tried to overcome this potential source of unequal treatment by counting waiting time from the start day of dialysis rather than the date of being placed on the waiting list. It is agreed that this is a more equal measurement of waiting time since it reduces inequalities resulting from late referrals. Furthermore Sweden has a unique Uremia education program for all ESRD patients informing them of the various treatment options as a way of bridging knowledge disparities between patient groups. Equal treatment is also illustrated by the exclusion of particular factors in decision making. Not considering social status, or chronological age in the strict sense are appeals to equal treatment. 13 4. DISCUSION Evaluating the process in reference to the A4R With range of factors and values identified there is a potential for reasonable disagreement leading to different decision outcomes between decision makers. There is also the potential for wrong (unfair) decisions to be reached in some cases. In instances where several relevant criteria have the potential to lead to different decision outcomes, the procedure used becomes important as a safeguard for fairness. It is in this respect that the A4R framework makes its most important contribution to the evaluation of priority setting process. We also recognize that the factors used in the allocation of scarce medical resources must be based on morally relevant values; otherwise, the resultant decisions would not be accepted as either fair or legitimate irrespective of the characteristics of the process in which they are allocated. One of the important criticisms the A4R has received is the diminished role it assigns to substantive values in the priority setting process. It can certainly be argued that Daniels and Sabin do make an allowance for the values that inform decision-making within the relevance condition of the framework [12]. The extent to which such values should be emphasized within the procedural approach of the framework is not very clear, however. A number of studies that have applied the framework have failed to address the underlying values and ethical norms on which decisions rest [9, 10]. We incorporate the substantive ethical values identified above into the evaluation of the priority setting process in relation to the A4R framework. Relevance Relevance has various dimensions; one being the perspective of the immediate stakeholders. This includes professionals who manage the transplant programs. The factors and values presented are those they report to using for decision–making, so we assume that they consider these relevant. Other stakeholders would be the ESRD population as those directly affected by the decision outcomes. Considering that there has been an ongoing dialogue with the kidney foundation which has not raised serious objections, it can be said that they too find the general factors made available to them to be relevant. It should be mentioned, however, that no study has measured the perceptions of the ESDR population. Perceptions of fairness in kidney allocation, amongst patient groups, are an important compliment to actual fairness, which would be an interesting area of enquiry [23]. 14 It may be argued that the general public should also be included in the discussion as stakeholders; since the field is so heavily dependent on public participation through organ donation. They are more intimately involved than in any other area of medicine. Input from the general population may contribute with relevant values which have been overlooked. Inclusiveness can have spin-off benefits, such as increasing awareness about the need for organs. Furthermore, it can lead to better appreciation for the difficult task that transplant programs perform, highlighting how centers balance complex and competing priorities to meet individual and population needs. A second dimensions is the degree that factor and values correspond with those identified in the literature, which other decision-makers in similar situations, and others involved in the discussion on resource allocation consider to be relevant. Investigating priority setting in the area of cardiac surgery, Walton et al. have identified a list of factors, considered in clusters similar to our finding, in the decisionmaking process, which contains a number of the factors identified in our study such as risk assessment, waiting time, and obesity. This illustrates the similarity in factors that have a role in priority setting in surgical specialties [9]. From a purely technical and clinical point of view, the factors that are identified in Table 1 are based on accepted evidence-based medicine and or experience supported by the literature. Brock (1988) states that, “there are no value-neutral selection criteria that could permit by-passing of the need to make ethical judgments in the recipient selection process” [24]. Even amongst what might be considered morally relevant values, there is certainly no unanimous consensus on the way they should be traded off in different cases. In his assessment of the ethical values in the distribution of organ transplantation, Brock identifies two major competing values that are traded off: achieving the most good with the limited resource and distributing it fairly [24]. In a more recent paper, Persad et al. [13] discuss four core ethical categories for the allocation of scarce medical resources: maximizing total benefit, treating people equally, favoring the worst off, and promoting and rewarding social usefulness; (this is often used during vaccination in pandemics by prioritizing healthcare workers, for example). These ethical values are clearly related to the two major categories identified by Brock. They also reflect the values to which decision try to balance in this study. These values identified in the study we believe are clearly based on morally relevant grounds. Even if a decision-making factor is generally agreed to be relevant, there remains a risk that it will be applied unfairly. This is true, for example, if its application undermines a formal requirement of justice 15 that similar cases be treated similarly. Clinical judgment and center specific policies, which fall under the professional and institutional levels respectively, are two factors which have the potential to lead to unfair decision outcomes. Clinical judgment we acknowledge is an integral and relevant part of medical practice. However it is important that variances stemming from this factor are contained. This is arguably already done through second opinions, but there is the possibility that some patients may not seek a second opinion. We believe that group decision making via gate keeper meetings, as practiced by some centers, is an approach with the potential to quell variations between decision makers by inviting more perspectives and adding to consistency. On the institutional level, center specific policies are another potential source of unequal treatment. An example of this is related to obesity, which is an important risk factor for a number of conditions and complications [25, 26]. However data regarding obesity and transplantation is inconclusive which leads to different policies [27]. While a centre with a rigid BMI cut-off denies a patient, a similar patient could be accepted at another center. Considering that patient under the Swedish health care have a right to equal treatment in having their health needs met, and that this unequal treatment runs counter to fairness, such differences should be minimized. One approach is to institute uniform BMI cut-off points between centres to ensure standardization. This can, of course, be extended to other criteria such as age or time elapsed since a malignancy (which is another area where differences were reported). This, however, is not the most ideal solution since it promotes over-reliance on rigid cut-off criteria. A better approach would be to try to discourage the use of defined cut-off values and to rely on more comprehensive criteria such as the overall fitness of the patient, of which BMI is a component but not the sole determinant. This we recognize will mean further reliance on clinical judgment, however we hold as mentioned above that these decisions are best made in a groups setting to invite as many perspectives. Publicity The general rules made available on hospitals websites do not reflect the full range of factors according to our analysis; nor do they reflect the underlying values on which they are based. The criteria for the allocation stage are generally better publicized than those for the assessment stage, which can in one way be explained by the increased cooperation between centres as a consequence of organ-sharing through Scandiatransplant. Generally speaking the patient level factors are better publicized than 16 professional and institutional levels factors. However as the relevance discussion above shows these levels are the potential sources of unequal treatment. Publicity of the full range of factors and the values on which priority setting decisions rest is necessary for any meaningful discussion on the fairness of the priority setting process. Publicity and transparency about the actual decisions and of the rationales underlying them is important. Transparency can have the added benefit that some patients who are unfit to seek a second opinion will not waste further public resources, which is likely if they are not satisfied by the rationale given by the first center. According to Walton et al., transparency regarding the rationales underlying decision-making is also important for patients who should seek a second opinion, so they may make the most informed decision together with their nephrologist [9]. Appeals/revisions Mechanisms for appeals and revisions are established and supported at all transplantation centres and nephrology units at the assessment stage. These are appeals within individual centres or appeals through second opinions. This openness to second opinion is beneficial for patients, as it increases opportunities for transplantation. It also has the potential to act as an informal regulatory mechanism of practices between centres, motivating them not to diverge too much from one another in their evaluation process. While appeals in the allocation stage are not possible in the traditional sense, it is important that the factors that form the basis of allocation decisions can be discussed and appealed against if found to be unfair. It is promising that such discussions do take place with the kidney foundation, which represents the ESRD population. Enforcement In Sweden’s decentralized healthcare, the centres are fairly autonomous relative to each other and to the national level. There were examples of informal regulatory mechanisms within the centers to counterbalance variations arising from individual clinical judgment decisions. The gate-keeper meetings are a way of inviting more points of view on individual cases in a collaborative effort. This decision-making within the centers has the potential to enhance fairness by ensuring that similar cases are treated similarly by a consistent group of decision–makers, which can reduce the influence of factors that lead to variation between decision-makers. 17 With regards to allocation once center had a sophisticated system of documenting and regulating allocation decisions at two levels: (1) it required all surgeons to justify their individual allocation, and (2) there was also a concerted effort to track allocation data in a computerized system, which provided an opportunity to draw links between certain allocation patterns and post-operative results. Another center recently began a similar initiative, which is not as developed. Together the above practices we believe are two best practices which deserve highlighting. 5. LIMITATIONS There are some methodological limitations which deserve mention. The first is that we did not have the resources to observe day to day priority setting in the centers which would have contributed to a richer data set by capturing decision-making in practice. Secondly we did not include any non-professionals as study subjects. Patients affected by ESRD, and even the general public who provide the resources necessary for transplantation, certainly have views that should be considered in the priority setting process. The study was mainly concerned with the professional point of view; it is, however, important to acknowledge that these are other perspectives that deserve attention in the future, which will create a more comprehensive depiction of the priority setting process. Finally, we chose the particular framework A4R; this approach is only one of a number of approaches to assess fairness in priority setting processes. However, given our interest in the procedural aspect of the priority setting process, the framework had some clear advantages over alternative approaches. Finally Sweden has a small population, and the priority setting process for kidney allocation differs from those found in the larger transplant systems such as Euro transplant and UNOS which are algorithm based, these together limits the generalizability of this study. However the assessment stage is similar across health care systems which all share the pervasive concerns for fairness. Findings and the discussion regarding the potential for professional and institutional level factors to lead to unfair treatment should of practical concern to all transplant programs. 18 6. CONCLUSIONS We believe that generally speaking the process can be considered to be fair. The factors described in this paper and the values on which they rest on the most part satisfy the relevance condition of the framework. There are however potential sources for unequal treatment which we have identified. These are clinical judgment and institutional policies relating both to assessment and allocation. The types of situation where these factors lead to unequal treatment such as in the case of BMI are certainly areas where reasonable disagreement can be expected since the medical evidence can be scant or contradictory. These differences in opinion across centers are equalized in some respect by the wellestablished appeal and revision mechanisms that we have reported. There is room for improvement in the areas of publicity and enforcement. The overall level of publicity of general guidelines is satisfactory, but it is fragmented— with some factors being better publicized than others. Publicity and rationalization of allocation decisions is an area that can be improved, since there was only one center with a well-established system for rationalizing allocation decisions. Even if this does not lead to opportunities for appeal in the traditional sense, it could act as a mechanism to facilitate consistency in decision-making within and between centres. We believe there are two policy proposals which merit consideration that would address issues of unequal treatment, as well as strengthen publicity and enforcement. These are the creation of national guidelines for the assessment for transplant candidacy and a national waiting list with centralized allocation. Swedish health care law requires that patients be treated equally. National consensus guidelines for the assessment for transplantation would contribute to better meet this requirement. It would clarify across the centers what factors are relevant for assessment. National Guidelines would by their nature be more accessible enhancing publicity. It would also contribute to further strengthen appeals and revisions since patients can defer to the guidelines if they believe they have been denied access unfairly. Finally they will also act as an enforcement mechanism to standardize practices. A national allocation system is where all patients are placed on one list and kidneys allocated to the (most appropriate) person near the top of the list no matter where they reside. The allocation would occur automatically, by a computer algorithm using criteria agreed upon nationally. This we believe will 19 reduce variance and generally contribute to a fairer allocation system. Again this system would better meet the condition for fairness in the A4R framework. Agreed upon criteria, that is widely accessible and enforced centrally. These policies would improve the consistency in decision-making between centers, and would generally better fulfill the requirements for fairness, in reference to the A4R framework. Participants in the study did not see a need for national guidelines or central allocation and believed that such guidelines would reduce flexibility in decision-making and would require more resources. The trade-off between reduced flexibility and in increased cost, on the one hand and the impact of a national assessment and allocation system on fairness, on the other hand, should be studied further. 20 Competing interests No competing interests Authors' contributions FO was involved in design of the study, was responsible for data collection, and was involved in data analysis. PC was involved in design of the study and data analysis. SW was involved in design of the study and data analysis. MOP was involved in data analysis. All authors were involved in drafting and critical revision of various versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Acknowledgements We thank all the surgeons, nephrologists, and transplant coordinators who took the time from their busy schedules to participate in the interviews and to share their knowledge of the field and their experiences in it. We also thank Gustav Tinghög for his valuable feedback on the manuscript 21 References 1. Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK: Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med 1999, 341(23):1725-1730. 2. Laupacis A, Keown P, Pus N, Krueger H, Ferguson B, Wong C, Muirhead N: A study of the quality of life and cost-utility of renal transplantation. Kidney Int 1996, 50(1):235-242. 3. Kalo Z: Economic aspects of renal transplantation. Transplant Proc 2003, 35(3):1223-1226. 4. Wikström B, Fored M, Eichleay MA, Jacobson SH: The financing and organization of medical care for patients with end-stage renal disease in Sweden. International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economic References 5. Scandiatransplant [http://www.scandiatransplant.org/] 6. Daniels N, Sabin JE: Settings limits fairly : can we learn to share medical resources? Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. 7. Kapiriri L, Norheim OF, Martin DK: Priority setting at the micro-, meso- and macro-levels in Canada, Norway and Uganda. Health Policy 2007, 82(1):78-94. 8. Martin DK, Giacomini M, Singer PA: Fairness, A4R, and the views of priority setting decisionmakers. Health Policy 2002, 61(3):279-290. 9. Walton NA, Martin DK, Peter EH, Pringle DM, Singer PA: Priority setting and cardiac surgery: a qualitative case study. Health Policy 2007, 80(3):444-458 10. Martin DK, Singer PA, Bernstein M: Access to intensive care unit beds for neurosurgery patients: a qualitative case study. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 2003, 74(9):1299-1303. 11. Martin D, Singer P: A strategy to improve priority setting in health care institutions. Health Care Anal 2003, 11(1):59-68. 22 12. Daniels N, Sabin JE: Setting limits fairly : learning to share resources for health. 2nd edition. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. 13. Persad G, Wertheimer A, Emanuel EJ: Principles for allocation of scarce medical interventions. Lancet 2009, 373(9661):423-431 14. Friedman A: Beyond A4R. Bioethics 2008, 22(2): 101-112. 15. Sabik LM, Lie RK: Principles versus procedures in making health care coverage decisions: addressing inevitable conflicts. Theoretical medicine and bioethics 2008, 29(2):73-85 16. Russell J, Greenhalgh T, Byrne E, McDonnell J: Recognizing rhetoric in health care policy analysis. J Health Serv Res Policy 2008, 13(1):40-46. 17. Greenhalgh T, Russell J: Evidence-based policymaking: a critique. Perspect Biol Med 2009, 52(2):304-318 18. Syrett K: A technocratic fix to the "legitimacy problem"? The Blair government and health care rationing in the United Kingdom. J Health Polit Policy Law 2003, 28(4):715-746. 19. Corbin, J.M. and A.L. Strauss, Basics of qualitative research : techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. 2008, Los Angeles: SAGE Publications. xv, 379 p 20. Boyatzis RE: Transforming qualitative information : thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. 21. United Network for Organ Sharing [http://www.unos.org/PoliciesandBylaws2/policies/pdfs/policy_7.pdf] 22. The Swedish National Center for Priority Setting in Health Care. Health care’s all too difficult choices? Survey of priority setting in Sweden and an analysis of the Riksdag’s principles and guidelines on priorities in health care. Report 2007. 23. Shapiro R: Kidney Allocation and the Perception of Fairness. American Journal of Transplantation 2007, 7: 1041-1042. 24. Brock D : Ethical issues in recipient selection for organ transplantation. In :Organ substitution technology: ethical, legal and public policy issues. Mathieu D, ed. Westview Press, Boulder, CO; 1988 25. Orofino L, Pascual J, Quereda C, Burgos J, Marcen R, Ortuno J: Influence of overweight on survival of kidney transplant. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1997, 12(4):855-. 23 26. Eckel RH, Krauss RM: American Heart Association Call to Action: Obesity as a Major Risk Factor for Coronary Heart Disease. Circulation 1998, 97(21):2099-2100. 27. Hanevold CD, Ho PL, Talley L, Mitsnefes MM: Obesity and renal transplant outcome: a report of the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study. Pediatrics 2005, 115(2):352356. 24 Figure 1. The conditions of the A4R framework [5,12]. 25 Table 1. Overview of factors and values impacting on priority setting decisions in Swedish kidney transplantation Patient level factors Cardiovascular status Malignancies Obesity Overall fitness Technical issues due to patient physiology Age ( biological age in assessment, age matching in allocation) Compliance-related issues (continued alcohol abuse, functioning social network) Risk benefit ratio (well-being on dialysis and patient motivation) Availability of living donor Other medical indications (reason for kidney disease, co-morbidities, urological complications, , immunological status, virological.) Blood group HLA compatibility Waiting time Special priority for young patients Need (rare situations) Professional Level factors Clinical judgment Risk aversion Resource utilization (constraints) 26 Institutional level factors Institutional policies ( obesity, marginal donor program) Scandiatransplant kidney exchange obligation Values Maximizing benefit Priority to the worst off Equal treatment 27