Final exam

Brian Sheehan – Final Exam

History of Modern China

Professor Lisa Tran

Loyola Marymount University

December 10, 2003

1

2

1) To describe the Twentieth-century in China as a “century of revolution” is more than apt. The century was ushered in with the 1911 revolution that toppled the Qing dynasty. From there, if we look at “revolution” in its simplest dictionary definition as: “sudden, radical, and complete change,” we can then view China’s twentieth-century experience as a series of numerous revolutions that stretched from 1911 to at least 1989. I will actually argue that it stretches from 1905 with the abolition of the civil service examination. As my thesis I offer that the difference between the twentieth-century being a century with revolutions for China and a century of revolutions was the impact and aftermath of one pivotal person: Mao Zedong. Mao, more than any other figure, was responsible for the continuing revolutions experienced in political, economic, and social spheres.

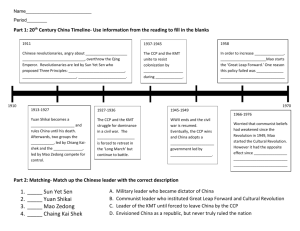

Using our broad definition of revolution, we can trace no less than ten revolutions in twentieth-century China: the abolition of the civil service exam (1905); the 1911 Revolution; the

May 4 th

Movement (1919); the War of Resistance against Japan (1937-1945); the Civil War

(1945-1949); the founding of the People’s Republic of China (1949); the Great Leap Forward

(1958-59); the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976); the Four Modernizations (1977 onward), the

Tianenman Square pro-democracy movement (1989). It can be argued that all of these events created sudden, radical change for large sections of the Chinese populace. We need only follow the progress of Jung Chang, her mother, and her grandmother to experience the poignancy of many of these revolutions within one family, as representative of many Chinese families.

Mao Zedong can be said to be part of, at the head of, or even posthumously involved in all of the revolutions outlined above. Born in 1893, as the scholarly son of a peasant who had prospered, Mao was twelve years old when the civil service exam was abolished. This would

3 have significantly changed expectations for a young man who had all the ear-markings of a youth ready to prosper in the Confucian tradition. Described by Snow (1968) as being “an accomplished scholar of Classical Chinese, an omnivorous reader, a deep student of philosophy and history, a good speaker, a man with an unusual memory and extraordinary powers of concentration” (pp. 92-93), one would be excused for thinking this was a description of a nineteenth-century jinshi holder, such as the great Zeng Guofan. Mao served briefly with the

Nationalist army during the 1911 Revolution; and he was at Beijing University in 1918-1919, the hotbed of the May 4 th

student movement. From this point on, Mao can be said to have stopped being a participant in China’s revolutionary history and said to have controlled -- or perhaps stage-managed -- China’s revolutions. Importantly, as we will see, Mao’s philosophy made him go beyond revolutions that were necessary for the emergence of a unified, socialist China (e.g.,

War of Resistance with Japan, Civil War, establishment of the PRC) to revolutions that were unnecessary and counter productive (e.g., Great Leap forward, Cultural Revolution).

Due to the central nature of Mao in many of these revolutions, I would like to explore the issue of what “revolution” actually meant to the founding members of the CCP, most notably to

Mao and his acolytes, such as Lin Biao, versus the techno-bureaucrats, as exemplified by Deng

Xiaoping and Liu Shaoqi. To understand what Mao actually meant by “revolution” is an exceedingly complex task. The popular view is that in the early days Mao actually had a strong and clear idea of what the objectives of revolution were. For example, some clear objectives as outlined in his interviews with Edgar Snow were: to distribute the vast wealth (e.g., land) of

China fairly among its inhabitants; to create a socialist society where all people were equal economically as well as politically; to educate the peasantry in general and to teach them the values of socialism, Marxism, and Leninism; to protect China’s territorial integrity against

4

Japanese and Western imperialism; to overthrow the Government of Chiang Kai Shek. The popular view then tells us that Mao became a despot: a man who used his power to protect his power, a man who hijacked the concept of “revolution,” using it to crush his enemies and subjugate the people to his will. In line with this interpretation, Snow (1968) perhaps gives us a glimpse of the future, when he notes that his first impression upon meeting Mao was

“dominantly one of native shrewdness” (p.92). Despite the popular view, in order to compare what Mao meant by “revolution,” versus the techno-bureaucrats, we must focus on what Mao said he meant. Only in this is there a fair contrast of interpretation.

Mao’s stance on revolution was that it was a continuous process. He believed that many people either by their nature, their pre-communist family position, or their intoxication from wielding party power, developed bourgeois habits that made them become obsessed with their individual advancement, economic welfare, and their position versus the rest of society. In his rhetoric, if not his mind, they were the bane of his existence: Chinese who felt they were better than the masses. Mao believed that this single tendency, be it called bourgeois thinking, rightism, or capitalist-roadism, was something that insidiously ate away at the fabric of Chinese society and threatened to stop or even reverse China’s march to socialism and ultimately to communism.

Only by continually opposing this force, and the people who were sucked into its vortex, could

Mao help China realize its communist dream. Mao tempered these tendencies on a grass roots level by introducing such concepts as “speaking bitterness”, criticism meetings, and thought reform. In spheres both economic and political, Mao linked his major programs directly to attacks (if not downright pogroms) against the people who exhibited bourgeois tendencies.

Therefore, when Mao was looking for a revolution in economic output, he could only see

China’s lack of progress as coming from bad seeds that needed to be weeded out. Hence, the

5

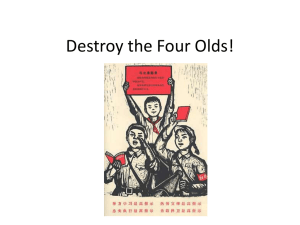

Great Leap forward was preceded by a social witch-hunt for “rightists.” This meant that any positive impact the Great Leap could have had was tempered by fear: fear to use common sense in application of collectivization and steel production. Similarly, when Mao’s ostensive goal was to rally the youth of China to push the communist agenda forward via the Cultural

Revolution, he combined it with a call to attack and destroy the old society, including “capitalistroaders”. Because both the Great Leap and the Cultural Revolution were as interested in vicious personal attacks as in societal and economic rebuilding, thereby creating pain, turmoil, and destruction on a broad scale, they will go down as unnecessary, pernicious revolutions rather than what they could have been: positive economic and social programs to take the next step in the development of a socialist society.

The techno-bureaucrats on the other hand were pragmatists. They believed that the key goal of the revolution had already been achieved (i.e., the defeat of the Nationalists and the founding of the PRC). To them, China had no further need for “revolution.” On the other hand,

China needed to be managed. Men such as Deng and Liu were to a significant degree less concerned with strict ideology. They believed, for example, that there was nothing inconsistent between perpetuating a socialist state dedicated to economic equality for the good of the masses and both training and taking advantage of those who clearly were a step ahead of the masses in terms of intellect and ability. “Experts” as they were called, were seen by the techno-bureaucrats as assets that would help China achieve its economic and social goals faster. To Mao, on the other hand, they were anathema. They thought they were better than the masses; they did not have the moral right to be at the vanguard. “Expertise” was pejorative in Mao’s view; to have it and to use it were wrong. Deng spoke for the techno-bureaucrats, and in support of expertise, when he said: “It doesn’t matter if the cat is white or black, so long as it catches rats.” In other

6 words, Deng was saying it doesn’t matter who does the job, as long as we do it the best we can.

In the final analysis, “the Liu-Deng line valued…bureaucratic approaches…technocratic abilities….[and] political stability in order to make the gains necessary for building a modern socialist state,” versus continual social and economic revolution (Schoppa, 2000, p.120).

It is clear that the twentieth-century in China has been one of continual upheaval and change consistent with the label “century of revolution.” It is also clear that Mao’s actions, be they driven by ideology, despotism, or paranoia, were decisive in molding a century where

Chinese citizens were impacted by continual revolution in their lives in wave after wave. Had

Mao died in 1950 and the techno-bureaucrats gained power, we would likely be calling the first half of the twentieth-century “50 years of revolution,” and the second half something very different, perhaps even “50 years of prosperity.” But to quote Chen Yun: “Had Chairman Mao died in 1956, there would have been no doubt that he was a great leader of the Chinese people…Had he died in 1966, his meritorious achievements would have been somewhat tarnished, but his overall record was still very good. Since he actually died in 1976, there is nothing we can do about it” (Schoppa, 2000, p.127).

2) From the founding of the Nanjing Government (1927) and the Jiangxi Soviet (1931) to the present day, China’s relationship with the West has been driven largely by ideology. Prior to 1949, the ideology of the GMD naturally pushed them towards the United States, while the ideology of the CCP pushed them towards the Soviet Union. Because the Communist Party’s ideology (i.e., Marxism-Leninism) was, from 1949 onward, extended from local political applications (e.g., socialism, land reform) to foreign policy, and was combined with an ignorance of the West among the PRC’s top leaders, I propose that China’s official views towards both the

7

United States and the Soviet Union were under-informed, leading to policies that were narrowminded and overly simplistic. The errors in judgment that led to these policies hurt China, and the Chinese people, more than they ever hurt the United States or the Soviet Union. Further, the

Chinese Communist Party’s insistence on viewing all international relationships and issues through an ideological prism, combined with the lack of worldliness of Mao Zedong in particular, led to the formation of images of the West and westerners, in the minds of ordinary Chinese that were erroneous to the point of being fantastic.

Looking first at China’s relationship with the Soviet Union, there are at least four distinct periods: 1) the period of aid and support to the combined CCP and GMD cause; 2) the period of

PRC support; 3) the period of distrust and separation; and 4) rapproachment. In the 1920’s, the combined forces of the CCP and GMD tapped the Comintern for organizational and military instruction. In particular, Mikhail Borodin became the chief advisor for the strengthening the pro-Sun Yat Sen forces, in effect making them both Leninist-style organizations. After the

Northern Expedition, a clear schism took place with the CCP naturally looking to Russia and the

Chiang Kai Shek-led GMD increasingly looking to the U.S. as the bulwark against communism.

From the founding of the Jianxi Soviet until the 1950’s, the CCP held up the Soviet Union as the idealized icon of the advanced soviet state. As Snow (1968) notes: “The Soviet Union probably made more profound impressions on the Chinese people than all Christian missionary influences combined” (p.353). And “among [revolutionary] young Chinese, Lenin was almost worshipped”

(p.352). Fed by idealism, young revolutionaries saw the Soviet Union in an unrealistic light. It was a model, a paragon of perfection. Few Chinese ever went to Russia, and even those who did turned a blind eye to its obvious social and economic problems. Chinese school children from

8 the founding of the PRC were taught that Lenin, along with Mao, Marx, and Engels, was one of the four greatest people who ever lived.

It is human nature that the higher we put something on a pedestal, the harder it falls off.

This was exactly the case with China’s view of the Soviet Union. Following Khrushchev’s assent to power in 1953, and the process of de-Stalinization following his secret speech in 1956, a rift occurred between China and the Soviet Union that was proclaimed as official Chinese policy in the early 1960’s. The rift would sour the countries’ relations for over 25 years. In doing so, it robbed China of a valuable ally, one that could provide it with scientific and industrial knowledge, and a window to the outside world. It is easy to surmise that China’s reaction to de-Stalinization was based on the Party’s impression that the Soviet Union was wavering on its commitment to Leninist ideology; but perhaps a better explanation is that Mao had a very personal reaction. De-Stalinization was a direct threat to Mao. It showed that he too could be toppled and replaced by progressive pragmatism. Officially, however, China was worried that Khrushchev had “negated the dictatorship of the proletariat” and that the USSR had

“allied itself with U.S. Imperialism” (Cheng, 1999, pp. 413-415) via the doctrine of peaceful coexistence. China, both in internal and external relationships, preferred dogma to moderation.

As Jung Chang notes (2003) of China in the late 1960’s: “Albania was China’s only ally – even the North Koreans were considered to be too decadent” (p.376).

China’s relationship with the United States from the 1920’s to today had at least four separate periods: 1) the period of convenient marriages; 2) the period of Nationalist support/PRC opposition; 3) détente; and 4) the period of full PRC recognition. From the formation of the

Jianxi Soviet, the communists learned to despise the United States. They did so on ideological grounds, given America’s position as the preeminent capitalist state, and its increasing position

9 as a colonial power, as well as for the fact that in a real sense the U.S. was at war with the Red

Army. Although the Reds fought the Nationalists, the U.S. provided tremendous economic support (e.g., $50,000,000 in wheat in 1933) and military support (e.g., U.S. pilots) that gave the

Nationalists the power to relentlessly attack the Red Army. The relationship between the U.S. and the CCP changed, however, following the Xian incident and the cooperation agreement between the CCP and the GMD. Throughout the war of Japanese Resistance, the United States was a convenient and powerful ally for the CCP. Mao and the Party could justify this alliance as an “anti-Fascist” alliance. In Mao’s words: “anti-Fascist alliances are in the nature of peace alliances, and for mutual defense against war-making nations. A Chinese anti-Fascist pact with capitalist democracies is perfectly possible and desirable” (Snow, 1968, p.104). By 1946, the view of the United States was favorable enough that the CCP agreed to talks with the GMD about the future of China mediated by an American General: George Marshall. Following the breakdown of these talks and the eventual founding of the PRC, American support swung solidly behind the Nationalists, while American success in the Korean peninsula threatened the fledgling nation militarily. In China, America was again seen as an evil empire. From the late 1940’s until the 1970’s, Party propaganda juxtaposed the “great successes” of the People’s Republic to the great failures of the West, as exemplified by the United States. In a country where the vast majority of people had never seen a person from the West, and where information was tightly controlled and twisted to the Party’s purposes, impressions of the West and westerners were wildly distorted. Jung Chang’s experience is notable. In her teens and young adult years, Chang was as highly educated, perceptive, and urbane as a communist youth could be in China, yet she believed that most children in the West went to bed hungry: “Think of all the starving children in the capitalist world!” She believed that foreigners looked like caricatures with wild red hair.

10

She believed that priests were men intent upon evil deeds. It is clear that the Chinese population believed the stories they were fed. They did not know how to do otherwise. The popular and

Party views of the West and westerners were also molded by the fact that the man who controlled the Party and popular images with an iron fist, Chairman Mao, had left China only once, for a brief visit to the Soviet Union. Therefore, Mao could delude even himself that much of his own rhetoric about the West was true. It is notable for example that Liu Shaoqi was labeled an “American Spy.” The most stunning event in twentieth-century Chinese-American relations has to be détente, and the visit of Richard Nixon to China. Nixon’s arrival, in the middle of the Cultural Revolution, was nothing short of a spectacular breakthrough for both sides.

It laid the groundwork for today’s relationship that has become one of cooperation, when possible, and mutual respect, if not one of trust and ideological agreement.

China has clearly had an ambivalent relationship with the West in the twentieth century.

While the Communist Party, in particular, looked to the USSR idealistically, their narrowminded, dogmatic approach to all things would ultimately lead to fear and distrust. In spurning the USSR, China lost the one source of advancement it had, and one that its people desperately needed. Conversely, the PRC’s deep revulsion for all things American ultimately collapsed under the imperative to engage the most powerful country in the world, a country that, no matter how much they tried to ignore it, would not just go away. In the end, the ones to suffer, as always, were the Chinese people. They lost the benefits of modernization, such as a higher living standard, that would have accrued from engaging the West, and they were left to feel deeply ashamed and embarrassed for themselves and their country when the bedtime stories of the evil West that they had been told turned out to be erroneous fantasies.

11