article-edit-1-part-i

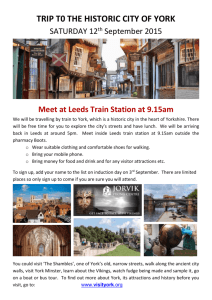

advertisement