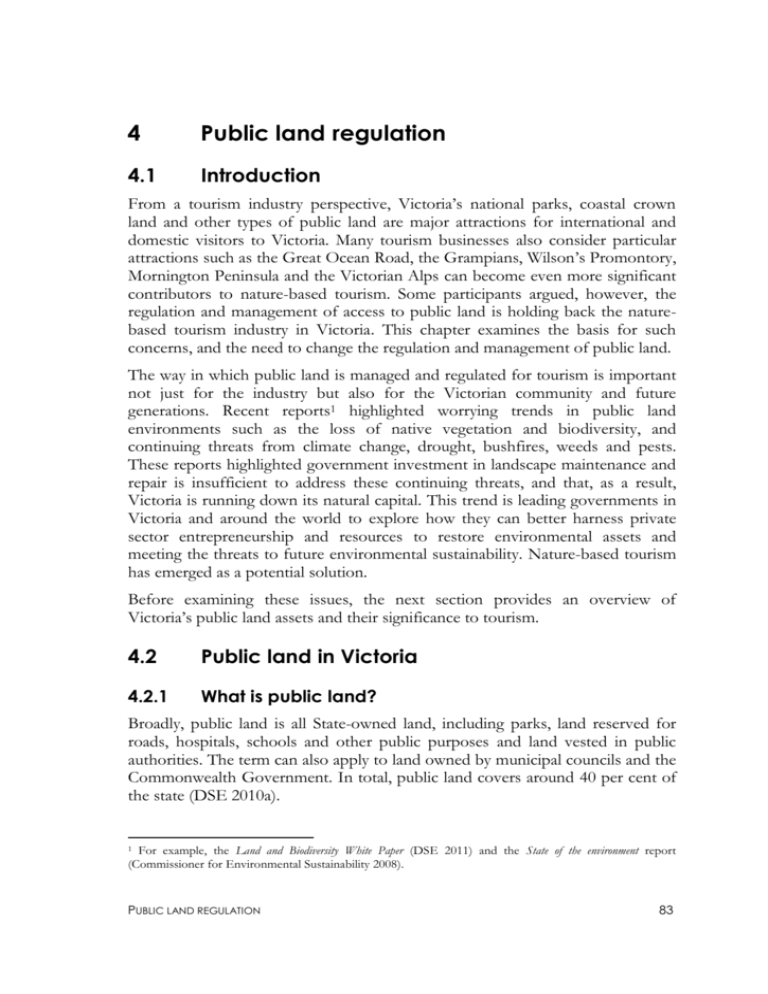

Chapter 4 - Public land regulation

advertisement