mira b. bergelson

advertisement

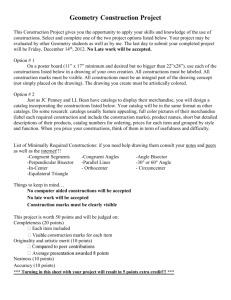

"Povelitel'nye predlozhenija v jazyke bamana." (Imperative constructions in Bambara).

Tipologija imperativnyx konstrukcij. V.S.Xrakovskij. (Ed.)

Sankt-Peterburg, 1992,

s.263-274.

Chapter 23 (author’s translation for future publication in English)

IMPERATIVE CONSTRUCTIONS IN BAMANA

MIRA B. BERGELSON

Moscow State University

1. Grammar notes. Bamana is a representative of a word-isolating language type

characteristic of the West African Manding group (Manding languages belong to the Mande

family, Niger-Congo phylum). Clause structure (syntactic relations) is manifested in Bamana by

means of fixed word order and auxiliaries. Basic word order is SOV. Isolation also serves as

morphological technique. Exclusions can only be found in word formation which operates as

adding up roots.

One typical feature of isolating languages is well attested in Bamana, namely that the absolute

majority of sentences in this language has more than one clause. The language has not got

adverbs as a word class, so all the adverbial meanings (benefactive, goal, adressee, locus, source,

time, condition) are expressed through adverbial clauses, which often are manifested as

complements, or non-finite predicates. Well known serial constructions are but an instance of

this category.

Bamana (more known as Bambara with English speakers) is spoken in the Mali Republic and

some other West African countries. The data used in this chapter reflects the so called standard,

or urban, dialect. A few examples are taken from the Beledugu dialect, which shows some

syntactic differences with the standard dialect regarding imperative constructions formation

(these examples are marked below). The material is taken from text sources, mostly of general

educational type - readers (Magasa 1978), grammars (Bird, Kante 1976), or elicited from native

speakers of Bamana. My main consultant on this research was a Mali linguist Mr. Adama

Konate whose untimely death in 1990 has been mourned over by everyone who happened to

know him.

Thus far I have seen only one research that looks at imperative constructions on West African

material (Demuth, Yanco 1979). Unfortunately, it is an unpublished manuscript.

Like many other West African languages, Bamana has lexical tones (cf. Courtenay 1974,

Creissels 1978, Diarra 1985). In recent years a ground-breaking work by Valentine Vydrine on

Manding lexical systems (see Valentine Vydrine. Manding-English Dictionary. Vol.1 St.

Petersburg: Dimitry Bulanin Publishers. 1999) has changed some previously held views and led

to much deeper understanding of the tonal sytems in these languages1. Besides that, Bamana

features grammatical tones - a tonal article - which marks NPs, and phrasal accents

charachteristic of types of utterances - questions and statements (Petrjankina 1983). In relation

to imperative utterances Bamana-specific data has not been obtained: there is just a common

correlation between the forcefulness and urgency of request and more pronounced phrasal accent.

Fixed worder order in Bamana means that a clause can be viewed as a sequence of ordered

positions, or slots, any of which may be occupied by elements of specific word classes. The

linear clause structure is as following:

slot #1 - subject NP

slot #2 - construction marker

slot #3 - direct object NP (for transitive constructions)

slot #4 - main predicate

slot #5 - adjunct (an adverbial NP with or without postposition).

There is no separate position (and thus - no category) for indirect objects.

Construction markers (CM) attach the clause to a situation by means of such concepts as:

aspect, modality, negation, semantic type of predicate. The following is the full list of CMs to

be found in Bamana clauses2:

bª incompleted (INC)

tª

incompleted negative (INCN)

yé1

completed transitive (CMPL)

má

completed negative (CMPLN)

3

0 ... -Ra - completed intransitive (CMPL)

bªnà

intentional (Int)

tªnà

intentional negative (IntN)

n‚, ná

intentional certain (Int)

bªkà

actual continuated (ActC)

bª ... lá actual progressive (ActP)

ká1

stative (Stat)

mán

stative negative (StatN)

ká2, kà2 dependent clause (DPND)

kàná

dependent clause negative DPNDN)

máná

hypothetical (Hyp)

yé2

imperative (Imper).

1I

would like to express my deep gratitutde to Valentine Vydrine who carefully read this paper checking all

the examples, especially marking tonal characteristics (the tones had not been marked when the initial

research on imperative constructions took place). His work and valuable comments improved

tremendously the quality of the proposed analysis and the data. It goes without saying that I bear all the

responsibility for any incorrectnesses left.

2 The following constructions markers are labeled according to their syntactic functions. In Idiatov 1998

(see Dimitry Idiatov. Semantics of Aspectual/Temporal Markers in Bamana. St. Petersburg. 1998.

Manuscript.) one may find a semantic description of a significant portion of these markers.

3 Here -Ra stands for a hyper-marker that appears as -na after nasals, as -la after laterals, and -ra in all

other cases.

Consider the examples4:

1a.

c¥®`

yé

fìní`

#1

#2

#3

man

CMPL

clothes

'A man put his clothes on the ground'

1b.

jí`

ká

#1

#2

water

Stat

'The water is warm'

1c.

à

tªnà

b¢

#1

#2

#4

he

IntN

go-out

'He will not leave the house'

dá

#4

put

dùgú`

#5

ground

só`

#5

house

k¢n¢

mà

postposition

kálán

#4

warm

postposition

Bamana syntax does not allow the sequence of positions in a clause to be broken by any inserted

elements. Thus, dependent clauses which in other languages may find themselves within the

linear clause structure, in Bamana will be positioned differently. Bamana multiclausal sentences

have two additional slots that allow for building more-than-one-predicate constructions.

Complex, multiclausal constructions are formed via quasi insertion of a dependent clause. In

fact, the dependent clause is moved out to the leftmost (slot #0), or rightmost (slot #6) position

reserved for topicalized information and "afterthoughts." A pronominal trace fills a

correspondent slot (subject, object or adjunct positions) within the matrix clause. This pronoun

(Pron) is anaphorically or cataphorically related to the dependent clause. Complex constructions

comprise sentences with relative, complement, coordinate clauses and nominalizations.

As for the construction markers, they fall into two unequal categories. The majority of them are

independent CMs that can be used both in monoclausal constructions and in any clause within

complex sentences. Only two of the CMs listed above have restricted distribution and can be

only used in dependent clauses. Those are CMs mana and ka2. The case with mana is simple

because this CM is only used within conditional dependent clauses. The opposite is true of ka2,

which is the most multifunctional of all CMs. As a marker of dependent predication it is used in

complements with modal and experiential verbs (see 2a.); in coordinate, same-subject

constructions (2b.); in serial constructions (2c.); in subjunctive clauses (2d.). CM ka2 may also

form a single-clause construction with optative meaning (3a., b.).

2a.

Mádù

bª

sé

ProperN

INC can

'Madu can ride a horse'.

2b.

à

he

4

kà

DPND

0

nà-ná

kà

à

CMPL come-CMPL DPND his

sò/`

bòlì

horse ride

mùsó` yé

wife see

Lexical tones are marked on vowels: "/", "\", "\/" mark, respectively, high, low, and rising tones. The

phrasal accent on the NPs is marked by "`" after the noun.

'He came and saw his wife'.

2c.

2d.

à

0

sín-ná

kà

he

CMPL head-for-COmpl

'He came out from the forest'

b¢

fúrátú`

k¢r¢

DPND go-out forest

n•

f‚`

bª

báará` kª

wálásá

à

my

father INC work

do

so-that

màló`

sàn

rice

buy

'My father works, so that his wife could buy rice'.

3a.

Álá

ká

hªrá`

Lord DPND happiness

'Let Lord make you happy'

kª

í

make you

3b.

fùnténí`

ká

kª

heat

DPND become

'Let the hot weather come'.

from

mùsó` ká

his

wife

DPND

yé

postposition

The occurrences of the ka2 marker fall into two categories: with high and with low tones. The

data shows that low tone occurences take place when the clause subject is omitted thus reflecting

higher degree of cohesiveness within the sentence (also see below examples in 17 - 18). Tonal

differences (along with the fact that neighboring languages demonstrate two phonetically

differing markers for these constructions) lead some scholars to the conclusion that there are two

unrelated ka-markers here. Still, syntactic and semantic in-language evidence allows for another

hypothesis which is favored in this paper. Syntactically, two tonal types are in complementary

distribution (low tone is manifested when the subject is omitted); semantically, they have in

common one core component of meaning, namely consequential dependence

('in-order-to'-relation) of one clause upon another. This relation may be manifested as in 2d., or

be an unexpressed speaker's request as in 3a., b., or be concealed behind the processes of

diachronic development of so called coordinate (2b.) or serial (2c.) constructions out of a

sequence of predicates whose positioning one after another reflects iconically the action

development.

Some complement constructions featuring CM ka2 are related to imperatives because the

predicate in main clause has causative performative meaning of inducement, and may form a

directive speech act. (Still, not all such complement constructions demand ka2 marker.) Most

frequently used directives are: bìlá 'force, compel', bàlí 'forbid', tó 'allow, let', yàmàrú 'allow', kó

'tell', j¥®n 'agree with, allow' in Beledugu dialect. These predicates differ syntactically in what

NP will occupy the slot #3. It is Addressee for bìlá, bàlí, and yàmàrú; it is Theme coded as a

pronominal trace of the complement clause for tó; and there is no filled slot #3 for j¥®n which

forms intransitive construction in this context.

4a.

n•

f‚`

bª

n•

bìlá

kà

nìn

báará` kª

my father

INC I

force DPND this

'My father makes me do this work'.

work do

4b.

sánjí` bª

n•

bàlí

rain INC I

prevent

'The rain prevents me from going'.

kà

táa

DPND go

4c.

n• f‚`

bª

n•

yàmàrù n•

my

father INC I

allow

'My father allows me to go'.

ká

I

4d.

à

f‚`

bª

à

tó

dén`

his

father INC it

allow child

'Father allows his son to go'.

ká

táa

DPND go

4e.

n•

f‚`

0

jÞn-nà

n•

my

father CMPL allow-CMPL I

'My father allowed me to go'.

ká

táa

DPND go

táa

DPND go

2. The imperative constructions scale. In a number of speech act theory studies, imperative

constructions (IMPs) are described as one of the four major types of utterances, namely directive speech acts, or directives.

Variety of IMP types and types of inducement expressed by them is immediately related to one of

the directive speech acts felicity conditions - the extent to which the speaker has control over the

addressee. It may mean that the speaker is respected by the addressee, is an authority for him, or

that the former has overall control over the communication act, thus being empowered to cause

the addressee to perform certain actions. The degree of such control depends on specific

correlations of social and individual statuses for a given pair of communication participants.

The higher this degree is, the less is the speaker obliged to take into account the addressee’s free

will; the less does the addressee exist for him as an individual.

Hierarchization of directives based on the degree of control is iconically mapped onto ordering of

IMPs in accordance with the amount of the adressee expicit coding in the surface structure. This

coding may include (without being restricted to) the following ways to “mention” the addressee

in the sentence: a separate NP, agreement markers, forms where the addressee’s grammatical

parametrs may be or may not be expressed. It can be better shown in a language with more

grammatical coding, like Russian. See (5):

5a.

5b.

5c.

Íå ìîãëè áû Âû îñòàíîâèòüñÿ?

‘Couldn't you please stop here?’

ß Âàñ ïðîøó, ÷òîáû Âû îñòàíîâèëèñü

‘I would ask you to stop here’

Ïðîøó Âàñ îñòàíîâèòüñÿ

‘I am asking you to stop here’

5d.

Îñòàíîâèòåñü!

‘Stop!’

5e.

Ñòîÿòü!

'Stop this car!'

5f.

Íè ñ ìåñòà!

'Don't you dare move this car!'

A few inferences relevant for understanding directives can be made out of this presumably

incomplete scale. Sentences in 5a. through 5f. form an hierarchy in accordance with a

pragmatically relevant parameter ‘degree of control’ irrespective of their form. A well-known fact

that IMPs in many cases represent indirect speech acts may be accompanied by an observation

that transition from direct to indirect speech acts is continual - also for directives (cf. Givon

1986).

The scale in 5a.- 5f. can be divided in several zones. There are indirect directives expressed by

interrogative sentences (5a.). For 5b. - 5c. I suggest the name ‘explicit directives’; those are

statements with performative verbs which explicate the speakers intentions, namely specific types

of inducement . The central part of the scale (5d.) is reserved for imperatives per se specifically marked forms or constructions expressing prototypical imperative meaning that does

not coincide with any of the directive performative verbs meaning. Thus Go! is not synonymous

to I order (tell you, request, demand, etc.) that you go. The former IMP reflects a different

communication situation - see Hausser 1980. To capture this difference I suggest a concept of a

‘zero, or implicit, performative’. It has its own meaning that can be described as ‘Saying “P,” I

cause you to do P’. The notion of a zero performative is confirmed by zero markers for the 2nd

person singular of the imperative mood in many languages, by zero expression of the subject and

the addressee of causation when they - as the speaker and the listener - are immediate participants

of a corresponding communication act. This performative approach to IMP is not a kind of

“trivial performativity” (Paducheva 1985, 23), but a way to functionally delineate core imperative

constructions (=Imper).

The rightmost part of the scale (5e. - 5f) also comprises indirect directives. They express

peripheral, not prototypical, inducement (necessity, status differences, obligation), which is

similar to the indirect directives in the leftmost part of the scale. What differs them from the

“classical” indirect speech acts (interrogatives or explicit directives) is the function that

grammatical forms or constructions play in the former ones: imperative meaning is a derived,

secondary, function for adverbs, NPs, infinitives in Russian. So, this part of the scale is called

‘derived indirect directives’. It should be mentioned that languages may express this 'derived

indirectness' in various ways: inflexional languages like Russian will use forms that don't allow

for grammatical reflection of listener's presence; more isolating languages - see English

translations - will use slightly different technique of 'dehumanizing' the addressee by shifting

attention from him/her to other objects.

Thus, the scale formed by constructions like those in 5a. through 5f. allows to describe IMPs in a

specific language not only within the framework of a universal paradigm, but also by functionally

as manifestations of certain types of directive speech acts.

3. Imperative constructions (IMP). Scarcity of formal means, characteristic of isolating

languages, is responsible for the fact that the repertoire of IMPs in Bamana is also quite scanty.

Still, it’s worth noting that a cell in a universal imperative paradigm can be filled by more than

one IMP, and this is due not o differences in aspectual or other verbal meanings, but to diversity

of mixed inducement types.

Assuming that A is Speaker, B - Listener, BB - Listeners, C - 3rd person, D - Actor performing

the requested action, the imperative paradigm will look as following:

Cell #1. D=B

Cell #2. D=BB

Cell #3. D=C

Cell #4. D=CC

Cell #5. D=A+B

Cell #6. D=A+BB

Cell #7. D=A (and there is B)

Cell #8. D=A (and there are BB). See Khrakovskij, Volodin 1986.

3.1. Core Imperative constructions (IMPER). Two variants of IMPER correspond to cells #1

and #2 in the above-mentioned paradigm - with a singular (D=B) and witha plural (D=BB)

addressee. IMPER with a plural addressee does not differ from other verbal constructions in

Bamana (compare 6b. below with 1a. - 1c.). IMPER with a singular addressee does not differ

from functionally similar constructions in many other languages (see 6a.): the predicate is a

simple verb stem, and both A and D are not coded in the surface structure.

6a.

bòlì;

run

'Run!'

6b.

á

yé

bòlì;

you-2ndPl

Imper run

'You guys run!'

lívúrú` tà

book take

'Take the book!'

á

yé

lívúrú` tà

you-2ndPl

Imper book take

'You guys take the book!'.

In 6b. á - 2nd person plural pronoun (with a high tone - not to be confused with à - 3rd person

singular pronoun) is a non-emphatic variant of áw - ‘you guys’.

Worth noting is that in the beledugu dialect (which features some differences in pronouns usage

as compared to the standard dialect) there is, besides the standard one, another variant of

IMPER with D=BB.

6c.

á //aá bòlì;

you-2ndPl

run

'You guys run!'

á //aá

lívúrú` tà

you-2ndPl

book take

'You guys bring {take?} the book!'.

There are two possible interpretations for the construction in 6c. The first is to postulate a zero

imperative marker, the second to view the pronoun á (aá is an optional variant with lenghtening)

as a form of address. The latter variant is preferable, because it is in correlation with optional

lenghtening of the vowel (compare to Russian Âàà-àñü!) and, which is very important, it does not

involve breaking of the linear structure of the clause in Bamana: subjects can not immediately

precede direct objects with no Construction Markers in between. In this case the beledugu

dialect differs from the standard one by only having one variant of IMPER, whereas the number

of actors of the requested action is clarified by a form of address.

3.2. Derived indirect imperative constructions. The interpretation of a CM ka2 given in

Bergelson 1985 suggests that this polyfunctional marker has one prototypical function underlying

all its occurrences, namely - to mark a dependent, subordinate clause (‘indirect mood’ marker).

In complex, multiclausal constructions (see 2a. - 2d.) this dependency is obvious and syntactic.

But besides that, ka2 is used in simple single-clausal constructions with optative meaning (see 3a.

-3b.). For such cases it is reasonable to postulate semantic dependency of ka2 from an implicit

performative ‘I want’.

7a.

n•

bª

à

fÞ

í

I

INC it

want you

'I want you to take the book'

7b.

í

ká

lívúrú` tà

you

DPND book take

'Why don't you take the book?'

ká

lívúrú tà

DPND book take

Expressing will is in the foundation of any speech act of causation, or inducement. That’s why

ka2 codes derived indirect IMPs. Expressing will stands here for the illocutionary function of

inducement. Depending on context or communicative situation sentence in 7b. can be also

translated as ‘Take the book!’ being a more polite, less coercive way to express the same idea as

in 6a. For other cells in the universal imperative paradigm (when D is not B/BB) IMPs with ka2

are the only grammaticized way to express imperative meanings.

8a.

8b.

ù

ká

táa

só`

k¢n¢

they DPND go

home in (=postposition)

'Let them go home / Why don't they go home?'

D=CC

án

ká

bámánánkán` kàlàn

we

DPND Bamana

learn

'Let's study Bamana' (title of a textbook of Bamana) D=A+B/BB

Thus, the only time when in one cell of the universal imperative paradigm one can find more than

one construction, is the case of D=B and D=BB:

9a.

lívúrú` dí

book

give

'Give (me) the book'

9b.

í

ká

lívúrú` dí

you

DPND book

give

'Why don't you give (me) the book?'

9c.

áw / á

yé

lívúrú` dí

you-2ndPl

Imper book

'You guys give (me) the book'

9d.

give

áw

ká

lívúrú` dí

you-2ndPl

DPND book

give

'Why don't you guys give (me) the book?'

The difference between core imperatives (IMPER) in 9a., 9c. and derived indirect directives in

9b., 9d. is not restricted to opposition of the two types of inducement - direct, prototypical, and

indirect, loaded with additional modalities. There is at least one context where only 9b.- and

9d.-type constructions are allowed for expressing imperative meaning. This is a conditioned

imperative context.

10.

ní

à

0

nà-nà

í

if

he

CMPL come-CMPL you

'If he comes to you, give him the book'.

m‚`

í

postp you

ká

lívúrú` dí

DPND book

give

3.3 One possible interpretation (D=A). In Khrakovskij, Volodin 1986 this case is described

as self-inducement on the side of the speaker which happens in the presence of one or several

listeners. In Bamana, the presence of a 'high-authority' listener, who in this or that way endorses

the action to be performed by the speaker, is a necessary condition for expressing this type of

inducement. So, here the speaker induces the listener to give him, the speaker, permission to

perform a certain action. Self-inducement per se does not have any special coding.

11a.

à

tó

n•

ká

nìn

it

allow I

DPND this

'Let me do this work'.

báará` kª

work do

11b.

á

yé

à

to

n•

you-2ndPL

Imper it

allow I

'You guys, let me do this work'.

ká

nìn

DPND this

báará` kª

work do

Sentences in 11a. and 11b. are multiclausal constructions with main predicate to -'leave, allow'

and a dependent clause with ka2 marker. The main clause of these sentences features the core

imperative construction (IMPER).

4. Prohibitive constructions. The dependent clause marker ka2 has its negative counterpart

kana that is used in the same construction types as ka2. Particularly, all prohibitive constructions

are formed with kana.

12a.

kàná

DPND-N

'Don't run!'

bòlì

run

12b.

í

kàná

you

DPND-N

'Don't run!'

12c.

à // ù/

kàná

d£nkílí`

dá

he // they

DPND-N

song

sing

'Don't let him/them sing the song' // 'Let him/them not sing the song'.

12d.

áw

// án kàná

táa

só`

k¢n¢

you-guys

// we DPND-N

go

house in

'Why don't you guys // we not enter the house'.

bòlì

run

The constructions in 12a. and 12b. fill the same cell in the universal imperative paradigm. The

former represents a core imperative construction, the latter - an indirect directive. Both

constructions are in their negative variants.

4.1. Preventive constructions. Strictly speaking, there are no preventive constructions in

Bamana; one can observe the corresponding meanings in certain conexts, but no specific coding

devices are allocated by the language to express these meanings. Compare 13 below with 12a. 12d.

13.

kàná

bònyà

DPND-N

get-bigger

'Don't get bigger'

Some observations can be made from looking at the constructions with definitely agentive verbs.

Those in Bamana are so called reflexive verbs which denote intentional and controlled situations.

They can be only used in transitive consructions where the DO position is occupied by a reflexive

pronoun i 'self' (it's initial function is 2nd person singular pronoun). Examples below are given

in a somewhat morphonological representation5

14a.

à

yé

í

bìn

he

CMPL

REFL fall-down

'He fell down (purposely)

5Understanding

this construction as having reflexive meaning demands obligatory ekision of the CM last

vowel - y'í instead of yé í. The latter variant (without elision) will represent a normal transitive

construction and will mean 'he made you fall-down'. I was pointed to this difference of form/meaning by

Valentine Vydrine.

14b.

à

0

bìn-nà

he

CMPL fall-down-CMPL

'He fell down (accidentally)

Sentences in 14 will differ in respect to imperative constructions formation.

15a.

í

bìn

REFL fall-down

'Fall down! (purposely)'

Core imperative transitive construction.

15b.

í

kàná

bìn

you

DPND-N

fall-down

'Don't fall-down!'

Prohibitive (=negative indirect directive) intransitive construction ??

15c.

*bìn

'Fall-down! (accidentally)'

Core imperative intransitive construction.

15d.

kàná

bìn

DPND-N

fall-down

"Watch out not to fall-down'

Preventive (=negative core imperative) intransitive construction.

Problems with interpretations for the sentences in 15a. - 15d. are due not only to the polysemantic

i, but also with the unclear status of the construction in 15b. Is this the "right" prohibitive

constrution corresponding to the IMPER in 15a? The "negative variant" of 15a.? From a

formal point of view, this is not: 15b., possessing characteristics of a negative indirect directive

intransitive, is a negative variant of neither 15a., nor hypothetical 15c. The "real" prohibitive

construction with an agentive, reflexive, verb should look like 15e:

15e. ??*

kàná

í

bìn

DEPND-N

REFL fall-down

'Don't fall-down!'

But the consultants were very sceptical about acceptability of 15e. Similarly, an indirect

directive variant of 15c. will not help to fix the contradiction between inducive meaning of the

construction and non-volitional semantics of the verb: í ká bìn - 'you'd better accidentally fall

down' is not an independent clause. It can only serve as a dependent clause in a sentence with a

directive predicate expressing volition•inducement, like n•bª à fÞ í ká bìn 'I want you you

fall down' (cf. 7a). Here the opposition between agentive and non-agentive meaning of the verb

is neutralized.

5. Imperative in multiclausal constructions. Inducement or causation may be expressed

only in the first or in both clauses of the construction. In the former case (so called 'conditioned

imperative'), the dependent clause can express the condition or the goal of the inducement.

16a.

16b.

dén` máná táa

í

mà

í

ká

lívúrú` dí

child Hyp go

you

postpos.

you

DPND book

'If the child goes into your dirction give (him) the book'.

give

à

ká

táa

Bàmàkó

wálásá à

bá`

ká

à

yé

he

DPND go

Bamako

so-that

he

mother DPND he

'Let him go to Bamako, so that his mother would see him'.

see

Both examples allow IMPs with any person, but Imper constructions are not allowed. Thus,

when converting 16a. in plural, the main clause representing IMP will look as following: ... áw ká

lívúrú` dí - 'you-guys give (him) the book'.

The second case is 'coordinated IMPs'. They may express the following meanings: request for

a sequence of actions (see 17a. - 17c) and request for a few simultaneous actions (see 18a. - 18c.).

17a.

dúmúní`

tóbí í

food

make you

'Make the food and eat it'.

ká

à

DPND it

17b.

í

sìgì

í

ká

à

REFL sit

you

DPND it

'Sit down and read it'.

17c.

wúlí

í

ká

stan-up you

DPND go

'Stand up and go'.

18a.

à

dún

kà

í

mìn

it

eat

DPND REFL drink

'Eat and drink'.

18b.

kàná

kàsì kà

à

DPND-N

cry

DPND it

'Don't cry and drink it'.

18c.

à

mì/n` kàná

it

drink DPND-N

'Drink it and don't speak'.

dún

eat

kàlàn

read

táa

mìn

drink

kúmá

speak

In the examples above the first part of the sentence is Imper - core imperative (prohibitive)

construction. The other part is a clause with a dependent marker ka. If the actions in both

clauses are understood as simultaneous, the subject of the coreferential subject in the second

clause has zero coding. It should be noted that in affirmative coordinate constructions in case of

coreferential subjects, the second one is necessarily omitted. For imperative constructions it is

optional, and the consultants confirmed preferential keeping of the subject for sequential actions

and omitting it for simultaneous ones. This allows for the iconic representation of more tight

cohesion of a situation in case of simultaneous actions. Compare 19a. and 19b. where presence of

the second subject slightly changes the meaning. (Also see the footnote #5, p. ... .)

19a.

dúmúní`

kª

í

ká

í

mìn

food

do

you

DPND REFL drink

'Have some food and (then) drink something'.

19b.

dúmúní`

kª

food

do

'Eat and drink'.

kà

í

mìn

DPND REFL drink

If the addressee of the inducement is not the listener, then the first clause can not be represented

by Imper, and the whole sentence is structurally analogous to a regular affirmative coordinate

multiclause construction with the same subjects. It is obligatory then to omit the same subject

in the second clause. (Also see the footnote #5, p. ... .)

20a.

à

ká

í

sìgí

he

DPND REFL sit

'Let him sit and write it'.

kà

à

DPND it

20b.

*à

he

à

he

ká

í

sìgí`

DPND REFL sit

sªbªn

write

ká

à

DPND it

sªbªn

write

6. Conclusion. The description of imperative constructions in Bamana suggested in this

paper does not cover all possible ways of expressing inducement and causation in this language.

When compared to the imperative constructions scale in 5a. - 5f., it is clear that only core

imperative constructions and indirect directives with CM ká/káná and surface subject (which

serve as a primary, grammaticalized way of expressing inducement of other than 2nd singular

person) were analyzed.

The issues that were more or less left out in this paper need at least some comment. Those

include explaining why IMPs with ká/káná are termed as indirect directives and how is the rest of

the imperative sonstructions scale expressed in Bamana.

6.1. The issue of indirect directives deals with two factors. First, the primary function of the

ka-marker is expressing volition; inducement is a secondary, indirect function. Second,

ka-constructions don't express prorotypical inducement (=strictly imperative meaning), but more

or less peripheral one. It is more than direct causation of the listener and may mean suggestion of

joint action, expressing wish to induce a third person to somenting, a request for permission to

perform an action, or a milder than normal request addressed to the listener to perform an action see 8b, 8a., 8c., 11a., 11b., 9b., 9d., respectively.

6.2. Correspondences of the sentences in 5a. - 5f. in Bamana will include only the counterparts

for the leftmost part of the scale - indirect directive interrogative constructions and expicit

directives like n• bª i bìlá kà táa -'I order you to go' (cf. with non-performative, assertive, use of

these constructions in 4a. - 4e.) Obviously, in this case the rules responsible for such

occurrences come from conventional strategies of language usage (indirect directives) and some

universal descriptions of language constructions contexts (explicit directives).

The rightmost part of the scale (5e., 5f. - derived indirect directives in Russian) is not represented

in Bamana for the specific reasons of its clause structure: the role of positions and constructions.

In particular, every sentence in Bamana must have expressed the main predicate position and the

Construction Marker position. Not a single NP can make a sentence without a special marker

whose meaning (existence, location, possession, or qualification and identification) is not

compatible with imperative. Probably, impossibility of the core imperative constructions

(Imper) in the main clause of the sentences with consitioned imperatives (see 10) is also due to

these structural restrictions.