What is Complexity Theory - Archive of European Integration

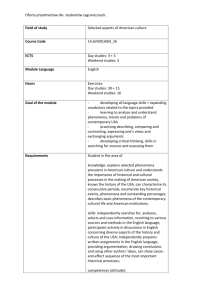

advertisement