Lab 2: Thinking like a Scientist

advertisement

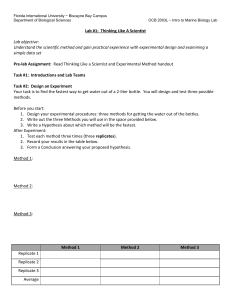

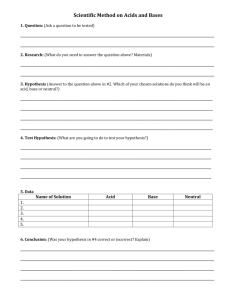

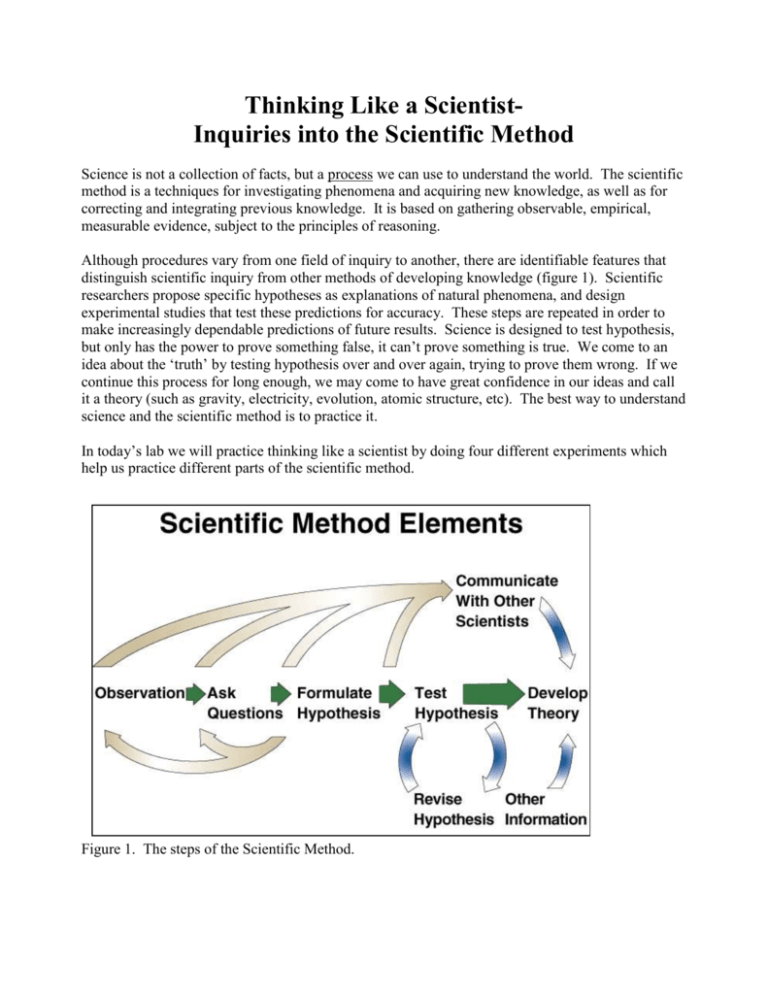

Thinking Like a ScientistInquiries into the Scientific Method Science is not a collection of facts, but a process we can use to understand the world. The scientific method is a techniques for investigating phenomena and acquiring new knowledge, as well as for correcting and integrating previous knowledge. It is based on gathering observable, empirical, measurable evidence, subject to the principles of reasoning. Although procedures vary from one field of inquiry to another, there are identifiable features that distinguish scientific inquiry from other methods of developing knowledge (figure 1). Scientific researchers propose specific hypotheses as explanations of natural phenomena, and design experimental studies that test these predictions for accuracy. These steps are repeated in order to make increasingly dependable predictions of future results. Science is designed to test hypothesis, but only has the power to prove something false, it can’t prove something is true. We come to an idea about the ‘truth’ by testing hypothesis over and over again, trying to prove them wrong. If we continue this process for long enough, we may come to have great confidence in our ideas and call it a theory (such as gravity, electricity, evolution, atomic structure, etc). The best way to understand science and the scientific method is to practice it. In today’s lab we will practice thinking like a scientist by doing four different experiments which help us practice different parts of the scientific method. Figure 1. The steps of the Scientific Method. Part 1. The Weight of Water Goals: Gain practical experience with glassware, laboratory balances, experimental design and descriptive statistics. Today will be our first experience in how doubt and skepticism are part of the scientific endeavor. We will show you three different kinds of laboratory glassware. All of them have graduations showing 100ml. Your mission is to determine which one is most appropriate for measuring exactly 100ml of water. Water has a density of 1.0 g/ml. This means that 100ml of water should weigh 100 grams. 1. First develop a hypothesis as to which one will be the most accurate and precise and write it down. Your idea should include a justification-why is it that you think this one is more precise than another. One very important part of science is our ability (or lack there of) to generalize from a relatively small data set. You’ll want to make your measurements three times on each type of glassware, this is what we call a replicate. You’ll report the mean (average) of each type of glassware. You will use the laboratory balances-Do not get water on them. In order to determine the mass of water in a container, you must first weigh the dry container, fill the container, weigh the container and water, and then subtract off the mass of the container. You’ll want to do this for each piece of glassware. Don’t assume that each beaker (or other glassware) has the same mass, weigh them all individually. Consistency is one of the most important skills in the lab and in all scientific investigations. You must fill your glassware exactly the same way each time. I will demonstrate how to fill them to the right level. You may want to use pipettes to add to your glassware a drop at a time. 2. Once finished with your measurements, calculate mean (average) for each type of glassware. 3. Conclusion: Please write a paragraph in which you address the following: You may do this in pairs. A) Describe the class data. B) Did your data validate your hypothesis? How? C) Did the class data validate your hypothesis (i.e. were the class data the same as yours)? D) What do the class data indicate regarding which type/s of glassware are good for accurate and precise measurements and which would you use if you needed approximately 100ml? E) Were your data the same or similar to that of your classmates? If yours were different, justify (develop a logical argument as to) why this might be so. F) Are some of the class data clearly different than the rest? Whose data should we believe and why? The Weight of Water- Data Table You may find this table a convenient way to organize your data. Beaker Mean Beaker + H2O H2O Graduated Cylinder Graduated Cylinder + H2O H2O Erlenmeyer Flask Erlenmeyer Flask + H2O H2O Part 2. Thinking Inside the Box Thinking Inside The Box Conference Dear Fellow Box Researcher: It is my pleasure to invite you and the members of your research group to attend the First Annual "Thinking Inside The Box" Conference. We would like you to present the results of your investigative studies on the contents of The Box. A reminder of the ground rules for these studies: 1. Investigators must, to the best of their ability, describe the contents of The Box. 2. The Box may never be opened; the contents may NOT be looked at. We look forward to your presentation at this conference. Sincerely, Chester Intrados Conference Chair You are working in your office at GenChemCo Industries one day when the above letter arrives. Of course, you had forgotten about your earlier commitment to assist The Box Studies Department in their quest towards a better understanding of the contents of The Box. So, you locate The Box sample that had been given to you and quickly gather your research group together. I. The Research Group Study "We've been invited to attend the Thinking Inside The Box Conference," you tell your group. "Let's see what we can do to put together a presentation for the conference. We need to describe the contents of The Box, but we may not open The Box or in any way look at its contents. Our goal is to characterize the contents, not guess what they are." As a group, pass The Box around to each member of your research team, and begin to record and organize your observations. You, as the leader of your research group, should direct this conversation. II. The Conference A member from each research group (not the leader or the recorder) will be asked to make a formal presentation to the conference on their group's findings. This presentation should summarize your findings and should not be a simple list of observations. You will record your findings on the board. The conference chair will act as a recorder. III. The Agency Each group will have five minutes to prepare a short research proposal. This proposal should indicate what, experimentally, is to be performed and what results might be expected. Each group will make their presentations to the conference. The conference will act as a review panel, with each member of the conference "voting" for his/her favorite proposal (an individual may not vote for his/her group's proposal). The two proposals with the greatest amount of support will be funded. Part 3. The 2 Liter Flush Task: You need to find the fastest way to get water out of 2-liter bottle. Objective: Test 3 methods of emptying the bottle to find out which is the quickest Materials: Plastic bottle Water Bucket to collect water Stop watch Procedure: Fill bottle with water up to the neck of the bottle Dump water into bucket (carefully), repeat. Before you start: 1. Design your experimental procedures, thinking of three methods for getting the water out of the bottles. 2. Write a Hypothesis about which method will be the best/fastest. 3. Write out your Methods which you’ll use. After Experiments: 4. Record your Results and graph them for easy interpretation. 5. Discuss your results 6. Form a Conclusion answering your proposed hypothesis. Data Table for 2-liter Flush. Record your time trials in seconds. Method 1 Method 2 Replicate 1 Replicate 2 Replicate 3 Average time Method 3 Part 4. Hypothetical Study Design Observations: You are a medical researcher developing a weight-loss drug. The rats you use as test subjects lose weight just fine, however, the autopsies of some of them show heart valve damage. Use the "Vocabulary of Experiments" section below, and your own understanding of the scientific method, to design a study to determine if your drug is causing the heart valve damage. Not all of the vocabulary terms may apply to your experiment. You need to take the observations and design an experiment. You will also make up the resulting data of that experiment and graph that data (or summary of data). Your conclusions should follow logically from your data and must address the question posed in the observation. Introduce the question and observations, explain your methods, explain your results, and have a clear conclusion. Make sure issues like replication and controls are adequately addressed. Hypothesis: Independent variable: Dependent variable: Control variables: Experimental group: Control group: Replicates: Treatments: Vocabulary of Experiments Experiments are organized and systematic attempts to coax information out of nature. They are often attempts to investigate and/or establish a causal relationship between two variables (i.e. cigarette smoking and cancer). For the sake of illustration, we will assume that we are agricultural scientists who have recently invented a new “green” fertilizer. We want to understand how it might be used to help a farmer increase our corn yield. Hypothesis: Typically a proposed explanation for the effect of the independent variable. These are very specific. Null hypothesis: The independent variable causes has no affect on the dependent variable. Variable: Something that changes or that may be manipulated (the addition of our fertilizer, amount of fertilizer, water, light, temperature, soil, etc). Independent variable: The variable that the scientist changes or manipulates (our fertilizer). Dependent variable: The variable that changes in response to the independent variable (yield of corn). Control variable: These are all the variables that the scientist endeavors to hold constant such that she knows that the change in the dependent variable is resultant of the independent variable (include things such as amount of water, soil type, light conditions, growing season, etc.). Experimental group: This is the set of experimental subjects that is exposed to the independent variable (corn plants that get the fertilizer). Control group: This is the set of experimental subjects that is kept under exactly the same conditions as the experimental group but does not receive the independent variable (corn plants that do not receive the fertilizer). Replicate: Typically scientists don’t just run one experimental subject or group, we run several (three or more) replicates so that we can compare them. If we ran just one we would not be able to detect anomalous results that might arise from contamination or some other factor (several different plots of corn. One might argue using several different corn plants, but replicates typically consist of several groups with many different plants). Treatment: Treatments are typically different applications of the independent variable. We might devise an experiment to test the effect of several different concentrations or applications of our independent variable (fertilizer).