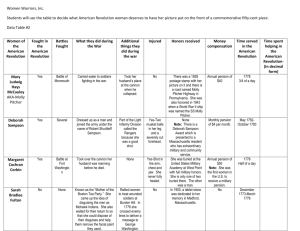

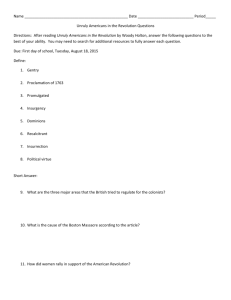

Women and the Revolution

advertisement

The American Revolution Women and the War for Independence Like all wars, the Revolutionary War greatly impacted the lives of women. Many American women actively participated first in the resistance movement, and later in the war itself. Because fighting took place on home soil, the war worked a tremendous hardship on civilian populations, which were vulnerable to marauding armies and raiding parties. The Revolution did not immediately improve the legal status of women. The Declaration, after all, asserted only that all men are created equal. But, over the long scope of U.S. history, this notion of equality would ultimately compel the enfranchisement of women and the establishment of women’s legal rights. The following documents illuminate some of these processes. Questions for students include: In what ways did women support the resistance movement and the war effort? Why would women choose to join the army, either as a camp follower, or as a soldier? Could the United States have defeated Britain without the aid of women? Did the war promote equality for women or did it subordinate women to men? How? Why? -1- The American Revolution Women and the War for Independence In 1774, fifty-one North Carolina women pledged to boycott British tea: "We, the Ladys of Edenton, do hereby solemnly engage not to conform to the Pernicious Custom of Drinking Tea . . . until such time that all acts which tend to enslave our Native country shall be repealed." This following political cartoon, published in London in 1775 and entitled “The Ladies of Edenton,” satirized those women, by illustrating the supposed ills that resulted from their activities in the public sphere. How does the cartoonist express his dismay for women’s political action? What symbols or imagery does the artist use to suggest that women’s political participation is problematic? Image available: http://memory.loc.gov/service/pnp/cph/3a10000/3a15000/3a15000/3a15070r.jpg -2- The American Revolution Women and the War for Independence Some women also participated in rituals of Revolutionary violence, as revealed in the following items. Selection from the New-York Gazette, and Weekly Mercury, October 2, 1775 Selection from a Letter by Abigail Adams to John Adams, July 31, 1777: It was rumourd that an eminent, wealthy, stingy Merchant (who is a Batchelor) had a Hogshead of Coffe in his Store which he refused to sell to the committee under 6 shillings per pound. A Number of Females some say a hundred, some say more assembled with a cart and trucks, marchd down to the Ware House and demanded the keys, which he refused to deliver, upon which one of them seazd him by his Neck and tossd him into the cart. Upon his finding no Quarter he deliverd the keys, when they tipd up the cart and dischargd him, then opend the Warehouse, Hoisted out the Coffe themselves, put it into the trucks and drove off. It was reported that he had a Spanking among them, but this I believe was not true. A large concourse of Men stood amazd silent Spectators of the whole transaction. Full text available: http://www.masshist.org/DIGITALADAMS/AEA/cfm/doc.cfm?id=L17770730aa How did these women assert their patriotism? Is it patriotic to attack private persons simply on the basis of their opinions? Were the women who assaulted the merchant acting out of love of their country, or simply in the interest of cheap coffee? -3- The American Revolution Women and the War for Independence Anticipating U.S. independence, Abigail Adams urged her husband, John, to provide legal protections for women under whatever new government the Continental Congress created. John did not take his wife’s request seriously. Selections from the correspondence of Abigail and John Adams Abigail Adams to John Adams, March 31, 1776 I long to hear that you have declared an independency, and by the way, in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies . . . Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a Rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation. That your Sex are Naturally Tyrannical is a Truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute. But such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of master for the more tender and endearing one of friend . . . Men of sense in all ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the vassals of your sex. John Adams to Abigail Adams, April 14, 1776 As to your extraordinary Code of Laws, I cannot but laugh. We have been told that our Struggle [the rebellion against Great Britain] has loosened the bands of Government everywhere. That Children and Apprentices were disobedient--that schools and Colleges were grown turbulent--that Indians slighted their Guardians and Negroes grew insolent to their Masters. But your Letter was the first intimation that another Tribe [women] more numerous and powerful than all the rest [had] grown discontented . . . . Depend upon it, we know better than to repeal our Masculine systems. We are obliged to go fair, and softly, and in Practice, you know We are the subjects. We have only the Name of Masters, and rather than give up this, which would completely subject Us to the Despotism of the Petticoat, I hope General Washington, and all our brave Heroes would fight.... Text available: http://www.nps.gov/archive/inde/education/U4-1WS1.htm How does Abigail equate the struggle of women with the fight for Independence? In what subtle ways does she liken husbands to King George III? Why would she do so? -4- The American Revolution Women and the War for Independence During the late 1770s, large headdresses came into fashion for elite women. This coiffure was introduced to Philadelphia during the British occupation, when it was worn by the wives and mistresses of the British officers. After Continental forces retook the city, American Patriots celebrated the Fourth of July by dressing up a black servant woman in the foolishly high headwear and parading her around town in mimicry of the British ladies. Selections from the correspondence of two Continental Congressmen, recounting the celebration of the Fourth of July 1778 (Or, the Whigs’ Great Wig) Richard Henry Lee to Francis Lightfoot Lee, July 5 1778” We had a magnificent celebration of the anniversary of Independence yesterday, when handsome fireworks were displayed. The Whigs of the City dressed up a Woman of the Town with the Monstrous head dress of the Tory Ladies and escorted her thro the Town with a great concourse of people. Her head was elegantly & expensively dressed. I suppose about three feet high and of proportionable width, with a profusion of curls &c. &c. &c. The figure was droll and occasioned much mirth. It has lessened some heads already, and will probably bring the rest within the bounds of reason, for they are monstrous indeed. The Tory wife of Dr. Smith, has christened this figure Continella, or the Dutchess of Independence, and prayed for a pin from her head by way of relic. The Tory women are very much mortified notwithstanding this. Full text available: http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(dg010190)) Josiah Bartlett to Mary Bartlett, August 24, 1778 Now for fashions; when the Congress first moved into the City, they found the Tory Ladies who tarried with the Regulars, wearing the most Enormous High head Dresses after the manner of the Mistresses & Wh____ s of the Brittish officers; and at the anniversary of Independance they appeared in public Dressed in that way, and to mortify them, some Gentleman purchased the most Extravagant high head Dress that Could be got and Dressed an old Negro wench with it, she appeared likewise in public, and was paraded about the City by the mob. She made a most shocking appearance, to the no Small Mortification of the Tories and Diversion of the other Citizens. The head Dresses are now shortning & I hope the Ladies heads will soon be of a proper size & in proportion to the other parts of their Bodies. Full text available: http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(dg010425)) What do these Congressmen’s letters reveal about their attitudes towards women? Towards women of color? Towards “Tory” women? Why would the Patriots of Philadelphia make this event part of their Fourth of July celebration? What did ridiculing British ladies have to do with the anniversary of Independence? How did Mrs. Smith attempt to deflect the satire that was aimed at her? -5- The American Revolution Women and the War for Independence In London, the creator of this British political cartoon used an image of the high headdress to parody not only the women who wore it, but also the American resistance movement. Entitled, “Bunker’s Hill, or America’s Head Dress,” (London 1776), this cartoon suggested that Americans wore their victory at Bunker Hill with ostentatious vanity or pride, much as this woman wore the Battle of Bunker Hill in her wig. Image available: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgibin/query/i?pp/PPALL:@field(NUMBER+@band(cph+3a04052)) So, partisans on both sides, the American and the British, used the fashionable, high headdress to mock their enemies. What does this suggest about prevailing attitudes about women? About fashion? -6- The American Revolution Women and the War for Independence Meanwhile, real life women continued to struggle with the war. Women who remained at home were vulnerable to predation by roaming armies. Selection from the letters of Eliza Wilkinson, a gentlewoman living in the Sea Islands of South Carolina, as she describes an invasion of her home by British soldiers (c. 1781). I heard the horses of the inhuman Britons coming in such a furious manner, that they seemed to tear up the earth . . . I had no time for thought - they were up to the house entered with drawn swords and pistols in their hands: indeed they rushed in in the most furious manner, crying out, 'Where are these women rebels?' That was the first salutation! The moment they espied us, off went our caps. (I always heard say none but women pulled caps!) And for what, think you? Why, only to get a paltry stone and wax pin, which kept them on our heads; at the same time uttering the most abusive language imaginable, and making as if they would hew us to pieces with their swords. But it is not in my power to describe the scene: it was terrible to the last degree; and what augmented it, they had several armed negroes with them, who threatened and abused us greatly. They then began to plunder the house of every thing they thought valuable or worth taking; our trunks were split to pieces, and each mean, pitiful wretch crammed his bosom with the contents, which were our apparel, &c. I ventured to speak to the inhuman monster who had my clothes. I represented to him the times were such we could not replace what they had taken from us, and begged him to spare me only a suit or two: but I got nothing but a hearty curse for my pains; nay, so far was his callous heart from relenting, that casting his eyes towards my shoes, 'I want them buckles,' said he; and immediately knelt at my feet to take them out. While he was busy doing this, a brother villain, whose enormous mouth extended from ear to ear, bawled out, 'Shares there, I say! shares!' So they divided my buckles between them. The other wretches were employed in the same manner; they took my sister's earrings from her ears, her and Miss Samuells' buckles; they demanded her ring from her finger; she pleaded for it, told them it was her wedding ring, and begged they would let her keep it; but they still demanded it; and presenting a pistol at her, swore if she did not deliver it immediately, they would fire. She gave it to them; and after bundling up all their booty, they mounted their horses . . . They took care to tell us, when they were going away, that they had favored us a great deal that we might thank our stars it was no worse . . . After they were gone, I began to be sensible of the danger I had been in, and the thoughts of the vile men seemed worse (if possible) than their presence . . . I trembled so with terror that I could not support myself. I went into the room, threw myself on the bed, and gave way to a violent burst of grief, which seemed to be some relief to my swollen heart." Text available: http://www.americanrevolution.org/women20.html Why did the British and American armies harass civilians? What options were available to women who were exposed to such dangers? What would you do if armed soldiers barged into your house, stole your clothing and jewelry, and threatened to harm you? -7- The American Revolution Women and the War for Independence Some women supported the war effort by urging their menfolk to fight. In 1776, the Pennsylvania Evening Post reported the speech of "an elderly grandmother of Elizabethtown, New Jersey" to her grandsons leaving for battle: My children . . . you are going out in a just cause, to fight for the rights and liberties of your country; you have my blessings . . . Let me beg of you . . . that if you fall, it may be like men; and that your wounds may not be in your back parts. Other women were not content to remain at home. Perhaps as many as twenty thousand women marched with the Continental army, providing vital services such as nursing, cooking, laundering, sewing, hewing wood, and others. Selection from a letter by Hannah Winthrop to Mercy Otis Warren, November 11, l777, describing the women who traveled with the British army. To be sure the sight was truly astonishing. I never had the least idea that the Creation produced such a sordid set of creatures in human Figure—poor, dirty, emaciated men, great numbers of women, who seemed to be the beasts of burthen having a bushel basket on their back, by which they were bent double, the contents seemed to be Pots and kettles, various sorts of furniture, children Peeping thro' gridirons and other utensils, some very young infants who were Born on the road, the woman bare feet, cloathed in dirty rags . . . Text: http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1999/summer/pitcher.html A few so-called “camp followers” actually took up arms on behalf of the Continental Army. Such women became mythologized as the celebrated “Molly Pitcher.” Selection from Joseph Plumb Martin, Ordinary Courage: The Revolutionary War Adventures of Joseph Plumb Martin, ed. James Kirby Martin (1993) A woman whose husband belonged to the artillery . . . attended with her husband at the piece [cannon] for the whole time. While in the act of reaching a cartridge and having one of her feet as far before the other as she could step, a cannon shot from the enemy passed directly between her legs without doing any other damage than carrying away all the lower part of her petticoat. Looking at it with apparent unconcern, she observed that it was lucky It did not pass a little higher, for in that case it might have carried away something else, and continued her occupation. Text: http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1999/summer/pitcher.html Resolution of the Continental Congress, July 6, 1779: Resolved, That Margaret Corbin, who was wounded and disabled in the attack on Fort Washington, whilst she heroically filled the post of her husband who was killed by her side serving a piece of artillery, do receive, during her natural life Or the continuance of the said disability, the one-half of the monthly pay drawn by a soldier in the service of these states; and that she now receive out of the public stores, one complete suit of cloaths, or the value thereof in money. Text: http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1999/summer/pitcher.html Recommended Reading: http://sdrc.lib.uiowa.edu/preslectures/kerber87/speech.html -8- The American Revolution Women and the War for Independence The famed Deborah Sampson dressed as a man, enlisted in the American forces, and fought in multiple campaigns. Sampson fought bravely and undetected, until an army doctor, attending her second wound, discovered that she was a woman. After the war, Paul Revere petitioned the Massachusetts government to award Sampson a pension. Sampson also appeared onstage in Massachusetts and New York, performing the military drills she had learned during the Revolution. Perhaps to overcome the gender expectations of her audience, Sampson often apologized for having disguised herself as a man. Title page from Herman Mann’s 1897 biography of Deborah Sampson, aka Robert Shurtliff (or Shurtleff) Image available: http://www.masshist.org/database/images/1639_ref.jpg Recommended Reading: Alfred F. Young, Masquerade: The Life and Times of Deborah Sampson (New York: Knopf, 2004) Emily J. Teipe, “Will the Real Molly Pitcher Please Stand Up?” http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1999/summer/pitcher.html -9- The American Revolution Women and the War for Independence Throughout the war, women found ways to contribute to the military effort, much as they had contributed to the resistance movement. In 1780, Esther Reed, a gentlewoman from Philadelphia, launched a fundraising campaign to benefit American soldiers. Reed and her co-organizers raised $300,000 in continental currency, which they originally intended to present to the army in cash. But General Washington, fearing that his soldiers would spend the money on liquor, requested that the women instead buy shirts for the poorly outfitted army. Selections from “The Sentiments of an American Woman” (Philadelphia, 1780) ON the commencement of actual war, the Women of America manifested a firm resolution to contribute as much as could depend on them, to the deliverance of their country. Animated by the purest patriotism, they are sensible of sorrow at this day, in not offering more than barren wishes for the success of so glorious a Revolution. They aspire to render themselves more really useful; and this sentiment is universal from the north to the south of the Thirteen United States . . . The time is arrived to display the same sentiments which animated us at the beginning of the Revolution, when we renounced the use of teas, however agreeable to our taste, rather than receive them from our persecutors; when we made it appear to them that we placed former necessaries in the rank of superfluities, when our liberty was interested; when our republican and laborious hands spun the flax, prepared the linen intended for the use of our soldiers; when exiles and fugitives we supported with courage all the evils which are the concomitants of war. Let us not lose a moment; let us be engaged to offer the homage of our gratitude at the altar of military valour, and you, our brave deliverers, while mercenary slaves combat to cause you to share with them, the irons with which they are loaded, receive with a free hand our offering, the purest which can be presented to your virtue, By An AMERICAN WOMAN. IDEAS, relative to the manner of forwarding to the American Soldiers, the Presents of the American Women… 1st. All Women and Girls will be received without exception, to present their patriotic offering; and, as it is absolutely voluntary, every one will regulate it according to her ability, and her disposition. . . 9th. General Washington will dispose of this fund in the manner that he shall judge most advantageous to the Soldiery. The American Women desire only that it may not be considered as to be employed, to procure to the army, the objects of subsistence, arms or cloathing, which are due to them by the Continent. It is an extraordinary bounty intended to render the condition of the Soldier more pleasant, and not to hold place of the things which they ought to receive from the Congress, or from the States. . . Full Text Available: http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/query/r?ammem/rbpe:@field(DOCID+@lit(rbpe14600300)) -10- The American Revolution Women and the War for Independence The American colonies and the early United States inherited from British common law a doctrine known as coverture. Under this doctrine, a married woman’s legal status was covered by that of her husband. The married woman virtually ceased to exist as a legal entity; her rights were subsumed within those of her husband. As the British jurist William Blackstone explained in 1765, "By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband: under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs every thing; and is therefore called . . . feme-covert.” (In many U.S. jurisdictions, vestigial notions of coverture persisted into the late twentieth century.) In the Revolutionary period, the legal status of most women was thus one of dependency. Daughters were legally dependent upon fathers. Married women were legally dependent upon their husbands. Applying this reasoning, some scholars have concluded that the notion of independence was an inherently masculine concept. Women could rarely be independent. American Patriots were fighting for economic and politically liberty that, by law, only a few women could experience. Perhaps because women were seldom considered independent in the same way as men, the Revolution did not secure for women the right to vote. Only one state permitted women’s suffrage. Article IV of the New Jersey Constitution of 1776 made no mention of sex, it merely declared: [A]ll inhabitants of this Colony, of full age, who are worth fifty pounds . . . and have resided within the county in which they claim a vote for twelve months immediately preceding the election, shall be entitled to vote for Representatives in Council and Assembly; and also for all other public officers, that shall be elected by the people of the county at large. Over the next three decades, perhaps as many as 10,000 wealthy women voted in New Jersey. But after a controversial election in 1807, the New Jersey legislature amended the law to prevent women from voting. Selections from “An Act to Regulate the Election of Members of the Legislative Council and General Assembly”” “[F]rom and after the passage of this act, no person shall vote in any state or county election . . . unless such person be a free, white, male citizen of this state.” Recommended Reading: http://www2.scc.rutgers.edu/njh/womens_suffrage/intro.php (Of course, women’s right to vote in the United States was not secured until passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1920.) -11- The American Revolution Women and the War for Independence In 1848, numerous women’s rights leaders, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, gathered at Seneca Falls, New York, to challenge the legal and social status of women. The attendees produced an extraordinary manifesto, their own call for independence, inspired by and patterned after Jefferson’s famous Declaration. Seneca Falls might justly be remembered as the birthplace of American women’s rights. The Declaration of Sentiments of the Seneca Falls Convention on Women’s Rights (1848): When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes that impel them to such a course. We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. Whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of those who suffer from it to refuse allegiance to it, and to insist upon the institution of a new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and, accordingly, all experience hath shown that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they were accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their duty to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security. Such has been the patient sufferance of the women under this government, and such is now the necessity which constrains them to demand the equal station to which they are entitled. The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world. He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise. He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice. He has withheld from her rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men - both natives and foreigners. Having deprived her of this first right as a citizen, the elective franchise, thereby leaving her without representation in the halls of legislation, he has oppressed her on all sides. He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead. He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns. He has made her morally, an irresponsible being, as she can commit many crimes with impunity, provided they be done in the presence of her husband. In the covenant of marriage, she is compelled to promise obedience to her husband, he becoming, to all intents and purposes, her -12- The American Revolution Women and the War for Independence master - the law giving him power to deprive her of her liberty, and to administer chastisement. He has so framed the laws of divorce, as to what shall be the proper causes of divorce, in case of separation, to whom the guardianship of the children shall be given; as to be wholly regardless of the happiness of the women - the law, in all cases, going upon a false supposition of the supremacy of man, and giving all power into his hands. After depriving her of all rights as a married woman, if single and the owner of property, he has taxed her to support a government which recognizes her only when her property can be made profitable to it. He has monopolized nearly all the profitable employments, and from those she is permitted to follow, she receives but a scanty remuneration. He closes against her all the avenues to wealth and distinction, which he considers most honorable to himself. As a teacher of theology, medicine, or law, she is not known. He has denied her the facilities for obtaining a thorough education - all colleges being closed against her. He allows her in church, as well as State, but a subordinate position, claiming Apostolic authority for her exclusion from the ministry, and, with some exceptions, from any public participation in the affairs of the Church. He has created a false public sentiment by giving to the world a different code of morals for men and women, by which moral delinquencies which exclude women from society, are not only tolerated but deemed of little account in man. He has usurped the prerogative of Jehovah himself, claiming it as his right to assign for her a sphere of action, when that belongs to her conscience and her God. He has endeavored, in every way that he could to destroy her confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life. Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation, - in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States. In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object. We shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and national Legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press in our behalf. We hope this Convention will be followed by a series of Conventions, embracing every part of the country. Firmly relying upon the final triumph of the Right and the True, we do this day affix our signatures to this declaration. Full text available: http://www.nps.gov/archive/wori/declaration.htm -13-