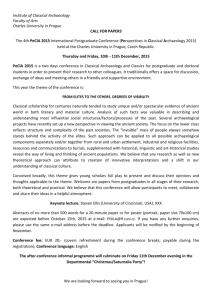

Conference Programme and Abstracts

advertisement

Classical music as contemporary socio-cultural practice: critical perspectives Friday 23 May 2014, 9.15am – 6.15pm, Council Room, King’s College London. Funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and Goldsmiths, University of London. Programme including Abstracts. 9.15am: Registration and coffee 9.30 - 11am: Welcome and session one. Professional lives: Open access or a closed shop? Chair: Hettie Malcolmson, Southampton University Gender in classical music practice: exploring older and newer forms of inequalities Christina Scharff, King’s College London This paper will explore and analyse gender inequalities in the classical music profession. The first part of the paper will provide a short overview of existing inequalities, which for example relate to under-representation, vertical and horizontal segregation, and the sexualisation of female players. Second, the paper will explore why these inequalities persist. By drawing on existing research on cultural work, neoliberalism and postfeminism, I will demonstrate how and why particular features of classical music work help perpetuate, rather than challenge, existing inequalities. The flexibility and informality that characterises work in the cultural sector, as well as the reliance on networks, tend to disadvantage women, as well as players from working-class and minority-ethnic backgrounds. Against the backdrop of this critical analysis, the paper will conclude by challenging the unspeakability of inequalities in the classical music profession and, indeed, the cultural sector at large. As Rosalind Gill has recently argued, inequalities may in part be reproduced through their very unspeakability. By drawing on existing and original research, this paper will attempt to bring these inequalities to the fore in the hope that such an analysis will instigate a more informed debate on contemporary classical music practice. The unchanging face of classical music: A reflective perspective on diversity and access Hadiya Morris, Royal College of Music The Guardian’s Stephen Moss once described the demographic of the average classical music audience as being “getting on in years, retired, white, middle class” (Moss, 2007). The legitimacy of this character, remarkably unchanged throughout history, has often been challenged academically with regards to gender and class, with thinkers such as Susan McClary and Pierre Bourdieu presenting varying understandings of them in music and society. Race, however, has largely been avoided in the academic forum, often left to the media to question and dispute. With statement such as the aforementioned by Moss and headlines such as ‘Why are our orchestras so white?’ (Day, 2008), the conversation often takes the destructive tone of a critique of classical music’s elitism and exclusivity as opposed to constructive reviews of how this tradition can be more effectively integrated into our ever-changing contemporary society. By bringing together research I, other musicologists, sociologists and philosophers have conducted and by offering my reflections of working in the music education as evidence, I would like to offer an alternative approach to this issue of classical music’s lack of access and diversity by deconstructing it as being an issue. Basing my reflection not solely on empirical research or sociological assumption but on organic, in situ observations, I hope to discuss the challenges in changing classical music’s current demographic whilst suggesting a new narrative on what the next generation of classical musicians could look like and why. DAY, E., 2008. ‘Why are our orchestras so white?’ The Observer [online], http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2008/sep/14/music.classicalmusicandopera MOSS, S., 2007, ‘Who is in the audience at a classical concert?’ The Guardian [online], http://www.theguardian.com/music/2007/oct/05/classicalmusicandopera1 The London orchestra as a prestige economy Francesca Carpos, Institute of Education As a professional orchestral bassoon player, I began to consider my experience of the orchestral community. My beliefs contained assumptions that appeared to thrive on ambiguity derived from, amongst other things, colloquial expressions such as ‘old boys’ network’. I believed that this expression described the ways that networking with ‘useful’ people, such as Freemasons, might be helpful in order for musicians to become successful. I began to question whether musicians perceived ‘prestige-seeking’ behaviour as necessary in order to gain work and therefore money. Competition between self-employed musicians is inevitable, because there is only so much work that can go around, and musicians need to consider ‘what you need to do to get ahead’. A central feature of this study is consideration of the possible contribution of the concept of a ‘Prestige Economy’ (Bascom and Herskovits, 1948; English, 2005; Blackmore and Kandiko, 2011), as a framework for illuminating perceptions of musicians in their orchestral world. Ways of understanding the nature of an individual’s interaction with others in an organizational setting is explored through the lens of this theory; and the model of a prestige economy may allow insight into the vulnerabilities, inequalities and tensions of orchestral life. 11.00-11.30am: Morning tea 11.30am-1pm: Session two. Music education and value Chair: Chloe Alaghband-Zadeh, University of Cambridge The rehearsal as cultural practice: the intimacy of authority in youth music groups Anna Bull, Goldsmiths, University of London This paper examines how the authority of the male conductor is constructed and experienced in youth classical music groups. Drawing on ethnographic work with a youth choir and two youth orchestras, it introduces three different modes of authority which conductors used in rehearsals: the ‘people manager’, the ‘charismatic charmer’, and the ‘cult of personality’. Conductors deliberately crafted these modes of authority, which relied on the embodied intimacy of this musical practice. This craft draws on gendered patterns of power and desire. This was particularly evident in one of the choral groups in my research, where it was enacted through the singers’ bodies mirroring the body of the male conductor. As a consequence of these gendered power dynamics, the girls in this choir talked about their conductor differently from the boys. While some girls experienced correction from the conductor as a form of gendered humiliation, or more positively as a pleasurable submission, these discourses were absent from the boys’ accounts. Despite the discomfort or resistance some of the young people voiced to me in private, they approached rehearsals with a willing trust which gave the public appearance of their consent to his authority. This enables this structure of authority to function uninterrupted. Venezuela’s El Sistema: social inclusion or exclusion? Geoff Baker, Royal Holloway, University of London Social inclusion has become the primary raison d’être for Venezuela’s El Sistema and its unprecedented funding, yet has received remarkably little critical attention in this context. This paper draws on a year of ethnographic fieldwork in Venezuela to examine the relationship between claims and realities, going beyond official narratives to take account of the perspectives of ordinary participants and critical observers. It examines the inclusivity of El Sistema’s practices, questioning whether the symphony orchestra and a competitive pre-professional program, both of which produce stratification, serve as motors of social inclusion. The program fosters tribalism but may weaken ties between young musicians and other social networks, principally their school peer group and family. El Sistema also sets up an adversarial dynamic with surrounding communities, which are treated as a problem rather than a partner. The program’s language of “escape” and “rescue” casts participants’ social context in the role of persecutor; collective activity does not therefore equate to social integration. Finally, the relationship between social and cultural inclusion is examined. A program that favours classical music and marginalizes local cultural forms may not serve as an effective source of inclusion. ‘In Harmony-Sistema England’ and cultural value Mark Rimmer, University of East Anglia This presentation will discuss empirical findings from an AHRC-sponsored research project designed to explore questions of cultural value in relation to In Harmony-Sistema England (hereafter IHSE), a social and music education programme whose approach and philosophy derives from the Venezuelan ‘El Sistema’ model. This model emphasizes intensive ensemble participation, group learning, peer teaching and a commitment to musical learning. In 2009 three pilot IHSE projects were developed in England and in 2011 the programme was extended such that today there are a total of seven IHSE projects operating across England. What is of particular interest, in terms of questions of cultural value, is that where most approaches to youth-focussed music participation initiatives in Britain have, to date, attempted to link music to forms of social good by employing popular music forms, IHSE predominantly uses classical and folk music, adopting a quite systematised learning approach and an orchestral model. This presentation will summarize findings from our research project then, with particular attention on the ways in which different stakeholders understand the forms of value embedded in their IHSE project activities. ‘Strings attached? Inclusive ensembles and non-orchestral progression’ Douglas Lonie, Research and Evaluation Manager, National Foundation for Youth Music The term ‘inclusion’ is often uncritically adopted in music education and cultural policy, leading to a variety of practices aiming to create or support ‘inclusive’ opportunities for young people. The Department for Education’s National Plan for Music Education states widening participation and equality of access as key intentions of the associated investment of public funds. However it is not made clear which specific practices this wider range of participants should be encouraged into, or how they are expected to progress. This paper explores definitions of inclusion as demonstrated by a selection of projects funded by the National Foundation for Youth Music (Youth Music) which seek to support musical, personal and social progression across a range of musical styles. Data provided by projects, as well as evidence from independent evaluations, indicate a broad range of individual, group, and ensemble music-making taking place in out-of-school contexts across a variety of genres. These data are compared to other nationally held data sets exploring mainstream and ‘outreach’ music education provision. Many Youth Music projects also conceptualise and measure progression differently from formal music education providers, drawing musical and non-musical trajectories of progression across a range of sites and over the life-course. This non-linear and non-predetermined approach to progression is also presented as an alternative to more traditional perceptions of progression in music. These findings suggest that a clearer and shared understanding of both ‘inclusion’ and ‘progression’ across music education and cultural policy will lead to a more diverse and appropriate offer for all children and young people. 1pm-2pm: Lunch (provided) 2pm-3.30pm: Session three. Traditions of practice Chair: Ruard Absaroka, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Classical music as enforced utopia Daniel Leech-Wilkinson, King’s College London In classical music composition, whatever conflicts may be engineered along the way, everything always turns out for the best. Similarly utopian thinking underlies performance: performers see their job as to carry out faithfully their master’s wishes, to be (as it were) brilliantly transparent; result happiness. But why should performers not have a critical role to play in re-presenting a score, just as actors are permitted – required even – to find new meanings and new relevance in texts? What does classical music performance tell us about ourselves that is not complacent or obedient? And what or whom are performers obeying, the long dead composer (and what is the ethical basis for that) or a policing system (teachers, examiners, adjudicators, critics, agents, promoters, record producers) that enforces an imaginary tradition from childhood to grave? Starting from the evidence of early recordings, showing that composers are misrepresented, this talk will seek to unpick some of the delusions that support classical music practice. Performing With TINA: Theory-Practice Inconsistencies in the Classical Music Profession Nick Wilson, King’s College London The focus of this paper is on theory-practice inconsistency in the British classical music profession, and the ‘early music movement’ in particular. I introduce the notion of the TINA formation, which takes its name from the theory–practice inconsistency made (in)famous by Margaret Thatcher, namely the view that “There Is No Alternative” (TINA) to the free market and economic liberalism. Elsewhere, a range of philosophers and sociologists, Freud, Marx, and Derrida amongst them, has used TINA. It refers to any complex totality in which a false structure or level or belief co-exists with a true one. We will find a TINA formation wherever there is a split between our theory and practice, or more proverbially between our “talk and our walk.” The paper introduces ten TINAs in all, covering the relationship between amateurs and professionals, the role of recording technology, the culture vs. commerce debate, and even in capitalism’s underlying reliance on what I term ‘enchantment’. It is suggested that bringing these TINAs out into the open represents a helpful step in transforming rather than reproducing structural practices and norms which otherwise don’t always work in the best interests of classical musicians, and society more generally. Experiences of sustaining and ceasing amateur participation in classical music Stephanie Pitts & Katy Robinson, Sheffield University As part of an AHRC Cultural Value project investigating lapsed and partial arts engagement, we have interviewed amateur classical musicians who have ceased their involvement in music-making, either currently or in the past. These ‘lapsed participants’ offer a new perspective on the contribution that musical participation plays in people’s lives: how it shapes their understanding of what it means to be a musician, affects their relationship with classical repertoire, and competes with other demands and choices in everyday life. In this paper we will review the qualitative themes of our study, and consider their implications for sustaining and supporting adult engagement in live classical music. Orchestras and musical terriblism Stephen Cottrell, City University One of the more noticeable developments in amateur orchestral music-making since the mid 1990s has been the rise of orchestras that describe themselves as ‘terrible’. While Alexander McCall Smith’s ‘Really Terrible Orchestra’, founded in 1995, is often taken as the starting point of this phenomenon, some commentators have sought to locate them historically within a tradition of English experimentalism that began with 1970s groups such as the Scratch Orchestra or the Portsmouth Sinfonia. Whether one accepts that or not, ‘terribilism’ in orchestral playing is now claimed from various ensembles in England and Scotland as well as in several parts of the USA. This paper will take a fresh look at this phenomenon, and consider how this celebration of amateurism and musical disunity casts a different light on widely-held ideals of orchestras as harmoniously organised microcosms of society. 3.30-4pm: Afternoon tea 4pm-5.30pm: Session four. Institutions and power: making space for creativity? Chair: Juniper Hill, University of Cambridge/University of Cork Newly Identified Creativities in the Practice of Professional Musicians: The Case for Institutional Change Pam Burnard, Cambridge University Our ability to imagine and invent new worlds is one of our greatest assets and the origin of all human achievement, yet the recognition and importance of the multiple creativities that provide the driving force for professional musicians is largely unrecognized in preparing them for the professional worlds they must navigate. Historically-linked and limited definitions of high-art orthodoxies exalt individual creativity. In presenting a multiplicity of creativities, other than those ascribed and mythologized by the accepted canon of ‘great composers’, this paper offers insights from research produced by the profession for the profession; these illustrate the need for us, in our work as higher education sector educators, to refine and accelerate institutional change. Plato said that ‘what is honoured in a society will emerge in that society’. To nurture creativities (in those pursuing a career in music, practicing and preparing for music performance and production, arts administration or music teaching, or any of a multitude of career options) music institutions need to be contemporary environments in which creativities are embedded, cultivated, modelled and resourced. While we might regard the historical legacy of creativities as being about domain specific musical processes, products and people, nevertheless, as will be argued in this presentation, a central ingredient in successful institutions is the ingredient of leadership. Throughout this paper, which explores insights from a large study of different types of musical creativities (as identified in the practices of professional musicians including composers, improvisers, singer-songwriters, original bands, DJs, live coders, and interactive sound designers), institutional leaders make decisions at a level of complexity that requires leadership creativities to be championed in ways that provoke invention, originality, imagination, entrepreneurialism and innovation. This is what makes new perspectives on who is professionally making the music, where it is being made, and for whom, as significant as the generative aspect inherent in practices such as sampling, resampling, mixing, mashing, and song writing and as important as composing, arranging, improvising and performing. What kinds of collaborative, communal or collective venturing underpin professional musicians’ activity at the beginning of the third millennium? An understanding of musical creativities which goes beyond the common forms of composition and improvisation and is both collective and individualized, is an imperative. The argument here is about the expansion of the concept of ‘music creativity’ from its outmoded singular form to its manifestations in multiple creativities and about how institutional change can be approached. Agency, autonomy and creative fulfilment in the lives of professional female musicians Victoria Armstrong, St. Mary's University College While opportunities for women have certainly improved and they are far better represented today in a range of music sectors, Creative and Cultural Skills (2010) found that women occupy only 32.2% of all music industry related jobs, they earn less, give up their careers sooner and experience more barriers to progression than their male counterparts. It has been shown that while ‘creative labour’ can be rewarding and fulfilling it is also a source of (self-) exploitation, is insecure, entails working for low or no pay through the gifting of free labour, requires high levels of commitment and results in bulimic work patterns. Using an innovative methodological approach combining visual research methods and digital ethnography, this paper presents the findings of an in-depth exploratory study into the working lives of five professional British musicians. It examines the nature of their work and seeks to understand how their freelance careers are experienced, supported and developed. Despite the largely negative picture presented in much current research about the creative industries, the findings here suggest that the freelance musicians in this study are able to exercise agency and experience high levels of autonomy in their musical lives in ways which enable them sustain freelance careers which are stimulating, musically rewarding and creatively fulfilling. Ideology, Power, and Discourse: New Music and the Power of Materialism Lauren Redhead, Canterbury Christ Church University The western European modernist tradition in music, here referred to as ‘New Music’, has a strong theoretical link with a utopian ideal. This is expressed not only by its composers, performers, and institutions but, supposedly, also in its materials and practices. However, this poststructuralist discourse analysis of artworks of the New Music tradition reveals an investment on the behalf of composers and institutions in an aesthetics of power which, far from the embodiment of a utopian ideal, functions as a form of social closure: asserting privilege amongst a relatively small group of practicing musicians and linking certain types of materiality to artistic quality. It considers how ideology and power are manifest in artworks, the way that institutions value artworks, and the institutionalised way that artworks are presented within the European modernist tradition. By aligning this analysis with Jacques Rancière’s conception of an ‘aesthetic regime of the arts’ this paper will describe how New Music requires its composers and its artworks to be both institutional and anti-institution, materialist and anti-materialist, consistently ‘new’ and also ‘traditional’, as exemplified by recent examples of New Music which purport to offer institutional critiques of the New Music establishment. Discordant Decisions: Challenging Power and Authority in Classical Music Competitions Lisa McCormick, Haverford College How should we explain scandals in the world of classical music? While the tendency in the media is to portray them as isolated cases resulting from individual failings, sociological accounts would typically point either to norm breakdown or struggles in the field of cultural production. This paper will outline an alternative view in which scandals are seen to emerge from cracks or fluctuations in the structural differentiation that is thought to have separated aesthetic and civil realms in contemporary society. Competitions will serve as the primary example. How do these organizations help to create the conditions for scandal by importing civil ideals of fairness and objectivity into the identification and recognition of artistic excellence? When they fail spectacularly to contain undue influence or to identify conflicts of interest, what do we learn about the structure of power and authority in the music profession? How might the problems experienced by competitions provide insight into other musical organizations blighted by scandal, such as the British music schools that have recently been contending with allegations of sexual abuse? 5.30– 6.15pm: Concluding keynote: Professor Georgina Born, Oxford University 6.15pm: Wine reception