Annex 7: Terms of reference for review

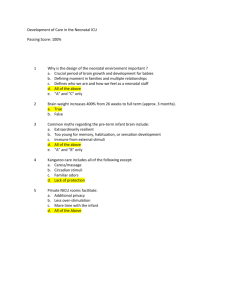

advertisement