Skjerdal against Mulvey

advertisement

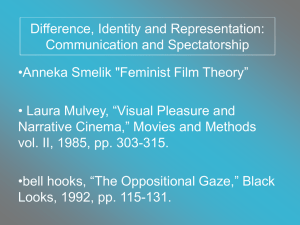

Laura Mulvey against the grain: a critical assessment of the psychoanalytic feminist approach to film By Terje Steinulfsson Skjerdal, Centre for Cultural and Media Studies, University of Natal, 1997. Abstract Since the middle 1970s, Laura Mulvey has been regarded as one of the most prominent feminist film critic. Her critique of mainstream cinema is built on Lacanian psychoanalysis, in which the differences between male and female spectatorship becomes a key component. In this paper, I argue that Mulvey's pscyhoanalytic approach to a very little extent is successful in dealing with the feminist dilemma. With references to "Thelma and Louise" (1991), I attempt to show that the psychoanalytic approach to film has three fatal weaknesses: (a) it is not easily applicable to film reading, (b) it assumes an unproven dichotomy between the active male and the passive female, and (c) it is simplistic in its condemnation of all Hollywood film. Content * * * * * * Mulvey's view of mainstream film: a typical feminist response Approaching cinema through psychoanalysis Critical assessment: how Mulvey's approach fall short The problem of applying psychoanalysis to film The problem of the active male vs. the passive female The problem of reading all Hollywood film as antagonistic The main contribution to film criticism by Laura Mulvey, whom I am about to assess in this paper, can be summarized as a challenge to both the audience and the film-maker. The audience is challenged in the way it assumingly reads film in a customary and uncritical manner; the film-maker is challenged by the degree to which he or she surrenders to the established norms of representing gender. A theorist and practitioner of feminist film criticism, Mulvey adopted and customized two central tools to analyse gendered address in classical narrative film: psychoanalysis and semiotic analysis. Following the publishing of her crucial essay «Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema» (1988b [1975]), an influential branch of feminist film theory was built on Mulvey’s theories as a vehicle to empower the broader feminist movement. This paper will trace the key elements of Mulvey’s theories, most notably psychoanalysis and feminist views on spectatorship. I will in this regard pay attention to the general theoretical significance as well as to the particular relevance to film criticism, since Mulvey throughout her writings seldom restricts herself to one theoretical aspect only. My specific aim in this section is to make clear what Mulvey’s critical theories have contributed to film criticism the past 20 years. I will then go on to critically assess Mulvey’s approach, with examples drawn from Thelma and Louise (1991). I hope thereby to show how a critical approach can question traditional film-making, but foremost I aim at proving that Mulvey’s psychoanalytic approach is insufficient to provide a sound modern film critique. The conclusion is twofold: firstly, that Laura Mulvey has contributed greatly to the criticism of gender representation in traditional Hollywood film [1]; secondly, that her reliability on psychoanalytic methods nevertheless proves to be an unfruitful approach to read films, both with regard to narrative content and with regard to her preoccupation with the relationship between film-maker and spectator. Mulvey’s approach to mainstream film: a typical feminist response Mulvey’s critique of traditional Hollywood film falls into the broad claim of feminist film criticism, as stated in «Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema»: «Film reflects, reveals and even plays on the straight, socially established interpretation of sexual difference which controls images, erotic ways of looking and spectacle» (p. 57). Film is thus seen as a reinforcement of traditional gender representation rather than a corrective. Crucial in this argument is the claim that the interpretation on behalf of the viewer takes place unconsciously, thus providing the basis for ignorance to gender oppression and subordination. It appears somewhat unclear from Mulvey’s writings whether she sees the portrayal of gender in mainstream film as a deliberate act performed by the production companies. On the one hand, the logical conclusion from the Freudo-Lacanian approach would be that also the film-maker’s thought is distorted through social learning. On the other hand, Mulvey utilizes the expression «manipulation of visual pleasure» to explain the magic of Hollywood style, as if the film-maker has a hidden male-biased agenda in mind. In either case, it is exactly the understanding of visual pleasure that is Mulvey’s project; in the first place to explain why the viewer is subject to a male reading of the film, and in the second place to propose solutions for an alternative way of reading and producing films. Mulvey claims that the main challenge for those who want to promote alternatives to the establishment is to overcome a patriarchal industry that has «left women largely without a voice» (1989, p. 39). The genres of melodrama and the western are used to prove this claim. With regard to melodramas, Mulvey argues that the sense in which these supposedly are able to equip women with a voice is contradictory. The female point of view will also here surrender to the overall patriarchal structure of society, Mulvey argues (1989). (Jackie Byars (1991) opposes this view, as I will note later on.) Central to Mulvey’s critique of traditional film is that popular culture discourages the audience from keeping a critical distance to the content (Seton, 1997). Most notably, however, is Mulvey’s assertion that the point of view that a camera holds is essentially male. The female viewer must therefore adapt to an identity other than her own, an argument that constitute the foundation for the psychoanalytic approach to film criticism. In this regard, Mulvey implicitly answers in the affirmative the question that has become central to feminist film criticism debate: «Is the gaze male?» Herein also lies Mulvey’s key to reading films: by help from Lacanian psychoanalysis. Approaching cinema through psychoanalysis One would not immediately think of psychoanalysis as a proper tool to read films, and perhaps it was partly the unexpectedness that made this approach popular after Mulvey presented it in 1975 . I will shortly summarize the main elements of this theory as it appeared in «Visual pleasure and narrative cinema» (1988b) [2]. The primary proposition of the psychoanalytic method, developed by Freud and further elaborated by Lacan, is that the woman is subject to personal and social depression through her lack of a penis. Her existence is thus decided by her desire to escape castration, an escape which turns out to be impossible. Psychoanalysis subsequently sees the male as physically and symbolically dominant, a dominance that is only threatened by his adopted fear of castration. Mulvey draws in this respect more on Freud than on Lacan, although she later goes on to use Lacanian terms such as «imaginary» and «symbolic». In transferring this theory to film analysis, particular attention is paid to the Freudian explanation of scopophilia – control through gaze. Mulvey contends that the scopophilic nature is evident in the way films are watched. Through narrative structure and conditions of screening, cinema provides a perfect climate for looking at another person as an object of sexual stimulation. This is the scopophilic function of sexual instincts. The ego function is also apparent, and develops as the viewer seeks to identify with characters on the screen. A central component in Mulvey’s adoption of Freud’s psychoanalysis to film spectatorship is therefore voyeurism, the pleasure in looking. Further, Mulvey distinguishes between the active male and the passive female. She argues that this dichotomy is further reinforced by mainstream film which combines spectacle and narrative in a speculative manner. The woman is in this view crucial to the narrative (as an object); and at the same time, she freezes the narrative in «moments of erotic contemplation» (p. 62). These moments ‘apart from time’ are evident for instance when the camera shows a close-up of Julia Roberts’ leg as she pulls on her stockings in the opening sequence of Pretty Woman (1990). According to Mulvey, such filmatic techniques are a result of the male gaze, and only proves how feminine qualities are married with the passive – both in the way the film is made and in the way the spectator makes meaning of it. The masculine, on the other hand, is perceived as more complex, more perfect. When reading films, the female spectator is left with two options: She can either identify with the male camera and the male object within the film, or she can identify with the female object within the film in a masochistic way (Man, 1993). Her destiny is that she cannot escape the male gaze as she reads the film. From this, it is evident that Mulvey’s psychoanalytic approach to film is a pessimistic one, and indeed deterministic. Mulvey also makes it a point to rediscover the three looks that are associated with film: that of the camera, that of the audience, and that of the characters. Her argument is that only the third of these, the viewpoint of the characters, is present in mainstream film. The two others are denied in order to strip the spectator of critical thinking and suppress information that may question the ‘realism’ of the picture. From the last argument in particular, it is no surprise that Mulvey’s answer to the feminist challenge is to call for production methods that extensively discard traditional film-making and instead pave the way for alternative cinema. In other words, she becomes a proponent for avant-garde film. Alternative film that challenges the basic assumptions of mainstream film is possible in Mulvey’s opinion, but «it can still only exist as a counterpoint» (1988b, p. 59). This adds to the theoretical pessimism that I will argue is evident from Mulvey’s psychoanalytic approach. It leads in a sense to a cul-de-sac where the male gaze penetrates not only cinema, but also the fundamental way in which gender is represented in society. To overthrow this patriarchal structure in a simple manner is in Mulvey’s opinion inconceivable – which follows logically from the psychoanalytic approach. Avant-garde cinema turns out to be her only response to mainstream cinema which supposedly is so structured by the male gaze that it is unable to accommodate images of women without fetishism (Enciso, 1997). The only way to facilitate a powerful feminist cinema is to disrupt traditional viewing pleasure, so to speak. In «Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’» (1988a [1981]), Mulvey reinforces her Freudian approach to film interpretation. In particular, the distinction between the active male and the passive female is further argued and extended. The conclusion remains the same, «Hollywood genre films structured around masculine pleasure, offering an identification with the active point of view, allow a woman spectator to rediscover that lost aspect of her sexual identity» (p. 71). The masculine identification is thus evident both from the point of the female character and the female spectator. In addition to bringing psychoanalysis into film criticism, Mulvey should be acknowledged for her application of semiotics in reading gendered address. Her approach in this regard did not represent a pioneer project in film criticism in general, yet it gave a new direction for feminist film criticism in particular. As Seton (1997) points out, the tools offered by linguistics and semiotics provided insights into the spoken (i.e. the conscious articulation of patriarchy), thereby filling in for the shortcomings of psychoanalysis (which analyses the unspoken, i.e. the unconscious of patriarchy). [3] Overall, Mulvey’s contribution can be read as a shift in film analysis from ideology critique to cultural forms critique manifested through the dominant male viewing pleasures into which everything has to conform. We have seen that the central explanatory component in this theory is Freud’s assumption that the female is rendered powerless through her awareness of a lack of masculine genitals. The female, then, is in this view unable to find ways of emancipation through a movie industry that only reinforces the male gaze. Thus, Mulvey denies that traditional filmic solutions are capable of destroying the male-oriented female image, and she consequently calls for an avant-garde technique that enables women to develop imageries that explore their own fantasies and desires. Mulvey’s own films (notably Riddles of the Sphinx (1976), which she co-produced with Peter Wollen), are often referred to as successful avant-garde responses to the challenge that stems from the psychoanalytic film criticism. The clue in these films is precisely that they supposedly turns the female passive spectatorial position to an active one. Mulvey’s crucial importance to feminist film criticism is evident from several recent commentators, for instance Elizabeth Wright (1992): «All subsequent feminist film theory working within a psychoanalytic tradition has begun with Mulvey’s articulation of the patriarchal gaze of narrative cinema» (p. 120). A critical assessment: how Mulvey’s approach falls short Having explained Mulvey’s main thoughts, we are now ready to turn to a critical discussion of her approach. I will organize the criticism in three broad categories: the difficulty that lies within psychoanalytic theory itself and its application to film criticism, the fatal tendency to dichotomize male and female natures, and the simplistic view that all Hollywood film is destructive. The bottom line is that Mulvey’s theories fall short of empowering the broad feminist movement. I am not arguing against her aim, only her method and theory. In so doing, I will draw on the reading of Thelma and Louise, a film that in my opinion in fact gives women a voice, although the film is highly marked by the Hollywood stamp both in narrative structure, cinematography and mise en scène. The problem of applying psychoanalysis to film As E. Deidre Pribram (1988) points out, Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalytic theories have been central to film studies because they forge a link between cultural forms of representation (here: film), and the aquisition of subject identity in social beings. However, my argument is that this link has proved difficult to establish in practice. Mulvey’s project is to search for a theory that sufficiently explains why Hollywood cinema is a threat to women. Her starting-point is thus fixed: She sees traditional narrative film as being destructive in that it forces the female to submit to established patriarchal norms. At this point, we already see a fallacy to which psychoanalytic film criticism tends to submit. It starts with the assumption that gendered address in traditional film is destructive, and goes on to explain this phenomenon without investigating the truthfulness of the initial presupposition. Then in the second place, as we are blinded by the seemingly obvious relevance of explaining a cultural representation through its psychological significance, the psychoanalytical film critic will utilize semiotic terminology partly derived from Lacan to explain the link between sexual identity and social determination (through the moving picture). The explanation seems convincing, yet it does not prove its claim – precisely because the order of assumptions and explanations/claims is reversed. There are too many assumptions and too little proof, as it were. The methodological approach of psychoanalysis is therefore a highly problematic (and subjective) one. The problems of a psychoanalytic film theory is also apparent from its preoccupation with only one aspect of the human nature, sexual desires. E. Deidre Pribram (1988) adds to this critique and claims that psychoanalytic theories «fail to address the formation and operation of other variables or differences amongst individuals, such as race and class» (p. 2). This notion is a valid one, particularly when considering the fact that most feminists will claim to be part of a broader movement that questions every part of patriarchal domination. Interestingly enough, Pribram goes on to argue that psychoanalytic models are also weak in that they deny the importance of the context; «no place is allowed for shifts in textual meaning related to shifts in viewing situation», hence ignoring the differences in viewership that might come about when people with different social and cultural backgrounds read the same movie. However, this position of psychoanalysitic film theory corresponds with its major premise that the gaze is merely male. This criticism will be further discussed under the next subheading. Christine Gledhill (1988) contends that a weakness of the psychoanalytic film approach (which she consistently calls «cinepsychoanalysis») is that it has derived its framework from the perspective of masculinity. The theory thus characterizes the feminine as «lack», «absence» and «otherness». However, Glenhill notes that there has been a development from early cinepsychoanalysis, i.e. from the 1970s, and that more recent approaches to the theory may be able to acknowledge feminine qualities as more complex than «male subordination». This is a valuable remark, and should be kept in mind as we examine Mulvey’s theories; it should not be taken for granted that she still supports all aspects of the approach as it appeared in the first publishing of «Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema» in 1975. However, in the introduction to the 1989 reprinting of the essay, Mulvey does reinforce the psychoanalytic approach, though she maintains that the practical side of the theory faced a different social climate in the 1970s. Teresa de Lauretis (1987) applauds much of Mulvey’s work, but is critical of the psychoanalytic approach. Her concern is particularly to prove the limits of this approach for film theory, and she argues that semiotic theories of iconicity and narrativity would be of more user to feminist film critics. De Lauretis’s critique seems to be sound in the first place, but how does she go about distinguishing semiotic theories from psychoanalysis, especially in the tradition of Lacan? Her response to this question appears to be incomplete. Zoe Sofia (1989), on the other hand, is easier to follow as she argues that a main difficulty with psychoanalytic cultural criticism is the inflexibility that results when the findings are generalized. The difficulty arises as the researcher tries to map out a larger theory from the analysis of the psyche; the problem is just that the findings will inevitably gravitate towards sociological conceptions already determined by the order of gender differences (which, again, stems from the presuppositions of the psychoanalytic approach). One of the more solid critiques of feminist psychoanalysis is provided by Jackie Byars (1991). Her argument is well-founded in that it points both to inconsistencies within psychoanalysis itself as well as to the problems of applying the theory to feminist film criticism. Byars notes how Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis sees the masculine as normative and the feminine as deviant, and further argues that this theory indeed «cannot account for resistance and ideological struggle; they represent, instead, the psychic mechanisms for reinforcing dominant ideologies» (p. 137). If true, this argument is all the more embarrassing to feminist psychoanalysists when facing the fact that feminism’s major project is exactly to reveal and overthrow dominant structures at all levels. Byars also contends that recent developments in psychology has discarded parts of Freud’s theories, whereas in film theory orthodox Freudianism still prevails. What, then, about the application of psychoanalysis to the actual interpretation of films? In my view, the reading of films through Freudian glasses proves how difficult it is to utilize psychoanalysis as a tool to understand patriarchal structures in society. A few examples from Thelma and Louise will illustrate my point. In a psychoanalytic reading, Thelma (Geena Davis) and Louise (Susan Sarandon) are seen as objects of their traditional, domestic world. Their ascribed task in life is to do the dish-washing, to nurture and to love their husbands. No other world is known to them. Thelma and Louise’s desire, however, is to escape and get away. In particular, they seek independence, freedom and space – qualities usually attributed to males. The psychoanalytic reading of this is obvious: The female’s innate hatred of castration leads her to worship masculine qualities. As the storyline develops and the two women run away to free themselves from their domestic environment, they indeed utilize masculine commodities to make their escape possible: a car, a gun, harsh language. Yet the psychoanalyst would not let the women get away with easy solutions. Eventually, they will have to surrender to their female destiny. I can therefore only think about one psychoanalytic interpretation of Thelma and Louise’s decision to speed their stolen car to the edge of the Grand Canyon in the end: They were ultimately trapped by the powers of the male-dominated society; the only way out – if not returning to their domestic world – was to give it all up. A positive interpretation of this last sequence is inconceivable in psychoanalytic terms. With regard to spectatorship, the psychoanalytic approach faces however difficulties. One of the problematic question is this: How can the male – who assumingly watches movies mainly for pleasure (voyuerism) – have pleasure in watching two women gaining power over other men? (Our presupposition here is that males actually did enjoy Thelma and Louise, which is evident from the popularity of the movie both among men and women.) The castration fear would certainly make this a painful watching experience for men as well as women. To this I simply reply that the psychoanalytic approach appears to be unable to deal with such problems. The problem of the active male vs. the passive female My second objection to Mulvey’s film theory arises from her rigid distinction between the active male and the passive female. In her view, woman is the object and man is the bearer of the look (the gaze is male). This dichotomy can to a certain extent be explained by the tendency for tying gender to biological determinism rather than to social development. Yet the psychoanalytic theory fails to account for differences within each gender, as I am about to argue now. In her argument against this dualistic model of gender identity, Sofia (1989) points out that the woman remains almost without any sexual identity in psychoanalysis since she is entirely defined in relation to the man. Sofia espands her argument by denying that symbolic language (as defined by Lacan) is adequate to masculine self-representation. Likewise, Sofia argues, textual excess or indecidability should not always be regarded as a feminine quality. Indeed, she concludes her paper with a crucial precaution that is highly relevant to a critical assessment of feminist film theories, namely that a failure to distinguish between feminine and masculine femininities and maternal figures can result in misreadings of masculine perversity as feminist progress. Such misreadings would of course go against the aim of the entire Mulveyian project. The fallacy of defining the genders as dichotomous categories becomes similarly clear from Mulvey’s assumption that the male is the bearer of the look. She expands this assumption to an application of the narrative film industry in order to show that both characters, film-makers and audience take the male gaze for granted. But how then, we must ask, is it possible to account for the differences that we apparently see in female characters within the same film? Mulvey’s answer is that there only appears to be a difference, a lesser or larger degree of masculine/feminine acting, but in reality all such individual characteristics are constructued to perfectly suit the overall notion of the man as the bearer of the look. The female spectator, then, unconsciously has to shift between an active masculine and a passive feminine identity. Pamela Robertson (1996) agrees with the assertion that female spectatorship is characterized by an oscillation between the active and the passive, but she also argues for a model that more accurately can account for «the overlap between passitivity and activity in a viewer who sees through, simultaneously perhaps, one mask of serious femininity and another mask of laughing femininity» (p. 15). Robertson’s solution is the position of camp, which she argues for extensively throughout her book, but it ultimately appears to be just another separatist ideology – which I doubt is a fruitful answer to the feminist challenge. Since Mulvey approaches the feminist gaze as utopic, how will she read Thelma and Louise? We can only guess. Because the psychoanalytic starting-point is that the female spectator is forced to read every action as either passive submission or active identification, it is likely that the critic will ignore the complexity of Thelma and Louise’s characters. Such a view becomes problematic because, as Glenn Man (1993) points out, Thelma and Louise generates a complex narrative process that can create «new fantasies for spectator appropriation» (p. 37). Man goes on to state what is exactly the core of my argument here: «What the narration of Thelma and Louise attempts to do then is to inscribe both women as subjects and agents of the narrative, give authentic voice to their desires, and mute the discourses of the male characters» (p. 39). If this is a sound observation, and I believe it is, then Mulvey’s assumption of the silent woman in Hollywood film is false. The problem of reading all Hollywood film as antagonistic We have seen that Mulvey argues for a feminist film-making practice that goes against traditional narrative film as much as possible. The assumption behind this argument is that the audience is so surrounded by traditional patriarchal norms that it is not able to critically read films unless an entirely different approach is provided. Mulvey’s response is to call for the avant-garde cinema, which she sees as a possible alternative to Hollywood, but «it can still only exist as a counterpoint» (1988b, p. 59). There is truly a sense of pessimism in that statement, a sort of Mulveyian «realistic dissidence» (cf. Theodor Adorno). Byars (1991) strongly objects to this claim that narrative film is all bad. Quite contrary to Mulvey, Byars sees the American melodramas of the 1950s as a creative tool rather than a destructive force. She shows that the Hollywood dramas not only encouraged the audience (both males and females) to interpret the filmic material, but also extended debates around issues of sexual divisions of labour, gender roles, and family structure. The kind of view that Byars advocates has gained more recognition in feminist circles in recent years. Film-maker Michelle Citron (1988), for instance, openly argues for a feminist use of Hollywood. In her opinion, the entry into mainstream narrative film-making will «broaden the work we [feminist film-makers] do and expand our understanding of visual culture and of ourselves» (p. 62). She even contends that traditional narrative film has more potential than alternative film in some areas because it opens up for contradictions, paradoxes and uncertainties. Another major point she raises against avant-garde advocates such as Mulvey, is that alternative cinema is inaccessible to many viewers. It contains an unfamiliar style and communicative form, and thus creates a gap that many viewers cannot overcome. Nuria Enciso (1997) adds to this critique, and maintains that radical films like Mulvey’s «have remained on the fringe and therefore have not contributed as greatly as they could have to altering the position of women within society». A main concern of Mulvey’s is the question of whether it is possible to obtain a true feminist gaze. By means of traditional narrative film, her answer is negative. On the contrary, Mulvey argues that only an alternative film method in the hands of feminists can possibly turn the gaze around. However, reality seems to be more complex than what Mulvey seems to suggest. That the film-maker is female does not of course ensure that the gaze will be feminine. And what is a feminine gaze? Film critics disagree on this point; many will say that there is no essential difference between a male and a female gaze. Furthermore, as Enciso (1997) points out, there are within each gender vast differences between individuals (there are blacks, older, younger, working-class, etc.). Such differences will often override gender differences as well, and makes the whole notion of gender separations highly questionable. It follows from this that Mulvey’s theories hardly can be said to have universal validity. Lastly, I will pay attention to the fact that contemporary mainstream cinema utilizes filmatic techniques and strategies of narration that would have been considered alternative only one decade ago. It is enough here to refer to Romeo and Juliet (1996) and Natural Born Killers (1994), which both have attracted large audiences although they in some ways break significantly with established narrative film. In the same manner, Thelma and Louise has been able to put on the agenda a traditionally marginalized issue, the issue of women emancipatoin. The last statement should be qualified to a certain extent; some commentators, such as Elayne Rapping, «certainly don’t think it’s a feminist movie» (1992, p. 30). However, I am not so concerned here with classifying what is a feminist movie and not. My argument is that the main concern for feminist film should not necessarily be to oppose mainstream film in all aspects. Rather, the focus should be on the issue itself, namely the struggle for women’s liberation. In this struggle, I contend that mainstream film may very well be a helpful tool, because, as Enciso (1997) points out, «the situation for women intellectuals and artists is already difficult enough without women discouraging their own participation in popular culture». In conclusion, I ought to give credit to Laura Mulvey for her important role in paving the way for a modern feminist film criticism whose main concern has been to give voice to marginalized sub-groups in society. I think here not only of the feminist movement itself. Nevertheless, I wish to maintain that Mulvey’s psychoanalytic approach has not been fruitful to an understanding of gendered address in traditional cinema. ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Notes 1. By «traditional Hollywood film» I mean mainstream movies which to a very little extent seek to challenge established norms and underlying societal ideologies. «Hollywood film» is always produced to reach a large audience, but needs not necessarily be made in Hollywood. The central claim in feminist film criticism is that Hollywood film fails to question dominant patriarchal structures in society. 2. Two other scholars who contributed to the development of psychoanalytic film theory in the mid-seventies were Christian Metz and Juliet Mitchell. More names could have been mentioned. However, this paper concentrates merely on Mulvey’s work since she appears to have been the most influential in developing a feminist film criticism based on psychoanalysis. 3. We may also speak of semiotics within psychoanalysis. Indeed, it is difficult to explain Lacanian psychoanalysis without using semiotic terminology. Lacan sees the phallus as the «signifier of signifers», the representative of signification and language. Moreover, the phallus signifies distribution of power and possession; a notion which in turn becomes a crucial element in Mulvey’s use of psychoanalysis. Lacan’s significance for feminist theory is extensively traced by Elizabeth Grosz (1990).