Dutchess County Poorhouse

advertisement

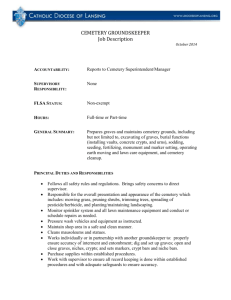

Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 1 The Brier Hill Cemetery at the Dutchess County Poorhouse Graves Graves Final Report Vassar College Digital Underground (Geology/Physics 241) Fall 2003 Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 2 Brier Hill Cemetery at the Dutchess County Poorhouse Executive Summary During the Fall of 2003, Vassar College’s Digital Underground class (Geology/Physics 241) discovered geophysical evidence of well over 800 graves at the Brier Hill Cemetery at the Dutchess County Social Service Department’s Millbrook Infirmary, formerly known as the Dutchess County Poorhouse. A 1934 survey showed 240 marked graves, numbered 1-604 with significant gaps. Some of the markers have two numbers to one marker with the numbers separated by one (e.g. 436/437) to fourteen (e.g. 492/478). In addition to the marked graves, numerous depressions are present where the soil of the grave has compacted, ranging from the subtle and barely visible to outlines of regularly spaced grave shafts, 2 m long by 0.5 m wide by 30-50 cm deep. The students from the class, working with local community members Virginia (Ginny) Buechele and Ed Lynch, spent nine field days surveying the site, first using visual clues as to the location of burials, then an array of geophysical tools (electrical resistivity, magnetometry, and ground penetrating radar) to support the visual identifications. These instruments measure subtle variations in the electromagnetic properties of the disturbed soil of the graves. During the course of the survey, we discovered an additional 30 markers that had been emplaced after 1934 and had not been surveyed. Visual and geophysical evidence suggests a total of approximately 840 graves on the 1.5 acre site- only 270 of which are marked. Based on the location and extent of the graves, we are able to outline the boundaries of the cemetery. In addition to the fieldwork, students conducted a search of the remaining historical documents for information concerning the people buried at the site. The remaining records include accounting ledgers, a record book of “paupers received and discharged”, a “burial book” which records the Poorhouse deaths and burial locations from 1934-1964(?), and burial permits from the Town of Washington (1919present). Using these records, we found 246 names of people believed to be buried at Brier Hill, and the “burial book” gave sequential numbers from 607 through 748, along with names, dates of death and burial, home town, race, and cause of death, amongst other information. Using these data, we were able to pin down the location of only 50 graves with known identification due to the number of missing grave markers. Submitted by: Brian G. McAdoo (Instructor) Students Nate Brown (Physics 2004) Evan Flugman (Astronomy 2004) Justin Minder (Geology/Physics 2004) Monica Rico (Geology 2005) Jessica Till (Geology/Physics 2005) Andrew Ulrich (History 2004) Community Activists Ginny Buechele (Geneologist) Ed Lynch (Engineer) Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 3 A note about the class This class was inspired by a similar course run by Professors Rob Sternberg and James Delle of Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. In the summer of 1998, I went along with Professors Delle and Sternberg to an archaeological site on the island of Jamaica. The site was an 18th Century slave village on a coffee plantation in the central part of the island, and consisted of the ruins of living quarters, animal pens, and a graveyard. The site was chosen, in part, to appeal to minority students, traditionally underrepresented in both archaeology and geosciences. At the site, we used three tools to identify buried remains- a Total station surveyor, a Cesium-vapor magnetometer, an electrical resistivity meter, and an electrical conductivity probe. Upon returning to Vassar, I was glad to discover that Professor Lucy Johnson in the Anthropology department had the same suite of instruments (except the conductivity probe) that she had purchased on a National Science Foundation Grant (almost $50,000 worth of equipment). Dr. Johnson was more than happy to share the equipment with her colleagues on campus, as was part of the intention of the grant. The ground penetrating radar system was added to the suite with a grant from the Vassar College Environmental Science Research Fund. Later that same year, I learned of a group of citizens in New Paltz, NY that were interested in exploring the role of African-Americans in helping to develop the region. New Paltz is well known for its historic district of preserved stone houses. French Huguenots escaping persecution in their native land built the 18th Century houses on Huguenot Street, and it was the core of the larger community of surrounding farms. What is not celebrated in the Huguenot history is the role that African-Americans, specifically slaves, played in helping to build the community. In their research, the group discovered evidence (deeds, newspaper mentions, etc.) of a slave burial ground on Huguenot Street. The burial ground is located in front of a private residence, somewhat separated from the historic district. When approached with a proposal offered by State University of New York at New Paltz archaeology Professor Joseph Diamond to dig some test pits to determine the nature of the graveyard, the landowner said, “No way!”. After reading about this in the local paper, I contacted the group and told them that I had a suite of tools that could potentially determine the extent of the burial grounds in a non-invasive way. I made a presentation to the group and the landowner, showing the results from our Jamaica project. Coincidentally, I had proposed to teach a Field Geophysics class around this same time. I offered the services of the class to survey the site, free of charge. Despite the fact that we would not be disturbing the land, the landowner still refused to allow a survey, reasonably concerned about his property’s integrity. Luckily, the Huguenot Historical Society came through with another site, Locust Lawn in Gardiner, NY, that had rumors of a slave burial ground associated with it. We surveyed that site, and the more we researched, the more we learned of the region’s dispossessed and how they are often forgotten and disrespected in regards to their burial grounds. This is the third survey done in the Mid-Hudson valley by the Vassar College field geophysics class, now called Digital Underground. The first offering, mentioned above, was a the Locust Lawn site, where we found a number of Huguenot graves, but only marginal evidence for an additional six slave burials. The next offering followed the fate of the slaves’ post manumission- to the Ulster County Poorhouse. The former Poorhouse site is located at the present Ulster Co. Fairgrounds and Pool Complex. There, we found evidence of well over 2,000 graves with only one marker on the entire site. This year’s project is the Brier Hill Cemetery at the Dutchess County Poorhouse, also known as the Millbrook Infirmary or County Home. Brian G. McAdoo Mary Clark Rockefeller Assistant Professor Geology and Environmental Studies Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 4 Introduction The Dutchess County Poorhouse is located in the Town of Washington, NY, near the Village of Millbrook (Figure 1). The Brier Hill Cemetery is located approximately ¼ mile south of the main buildings. Little was known of the graveyard before this survey. The Dutchess Co. Department of Social Services, which uses the property as a mental health facility, has a copy of a survey of the graveyard made in 1934 (Figure 2). The map shows 242 graves, with numbers that correspond to markers as they were in 1934. Numbers on the markers ranged from 1 to 604, but there are significant gaps- notably there are no numbers in the 100’s, 200’s or 300’s. Also, there are a number of markers with two numbers, separated between 1 and 14 in the sequence (e.g. 492/478- see Figure 3). Initially, it was thought that the markers with more than one number indicated mass graves where more than one individual (tied to a number) was buried. Before we started with the geophysical survey, we walked the site of the graveyard, noting the location of the markers as they compared with the 1934 map, and also noting the location of markers not on the 1934 map. In addition to the markers were a number of depressions in the ground where graves had settled, leaving a 2 m by 0.5 m hole in the ground. From the initial walkover, it became clear that there were far more than 242 graves on site. Our goals in this study are to find out: The extent of the Cemetery. The number of graves in the Cemetery. The history of the Cemetery. Who is buried there? The stories of those buried there. We undertook a geophysical and archival survey of the site and the remaining documents that pertain to the site. We used a suite of instruments including a Total station surveyor, an electrical resistivity meter, a Cesium-vapor magnetometer, and a ground-penetrating radar to map the site and the associated soil properties. Records from the site were saved by the Dutchess Co. Department of Social Services, and were made available to our study, as were burial records from the Town of Washington. By using the geophysical tools to assist our visual observations, we are able to understand the layout of the cemetery. The various records provide insight into the people and stories of this piece of forgotten history. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 5 Figure 1. Location of the Millbrook Infirmary (as the Dutchess Co. Poorhouse is called today). The cemetery is located ¼ mile south of the infirmary. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 6 Figure 2. 1934 survey map of the Brier Hill Cemetery. The map has 242 marked graves ranging in numbers from 1 to 604. The map also shows a marble headstone/footstone at the southern end. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 7 History of the Dutchess County Poorhouse (Ulrich) The Dutchess County Poorhouse in Millbrook came about due to a series of disputes between the City of Poughkeepsie and the County authorities. Prior to 1863, the county’s poorhouse had been located in the City of Poughkeepsie. However, during the Civil War there was confusion as to which entity, the county or city, ought to care for the poor. In order to resolve the dispute and to move to a more central location, the state legislature authorized Dutchess County to sell its old property and erect a new poorhouse. In May of 1863, the county board of supervisors purchased 74 acres outside of the village of Millbrook, which constitutes the present site of the poorhouse and “Brier Hill.” The new county facility was completed in April, 1864 and the first inmates arrived in October of that year. The main structure was two stories and constructed of brick. Also built that year were an insane asylum and a house for the keeper of the institute. The total cost to the county ran to approximately $45,000.1 The concept of a poorhouse was to uplift its occupants, and provide them with shelter in return for their labor. Often, conditions inside these facilities left much to be desired, and the Dutchess County Home was no exception. Soon after it opened, the deteriorating conditions at the home were being exposed. A New York Times article from December 15, 1878 remarked, “The stairway leading from the garret to the floor below is not over two feet wide. There is an entire lack of fire-escapes. The ventilation of the building has been entirely neglected. There is no place on the premises on which to place the sick.”2 Adding to the misery that occupants faced, a “Children’s Law” enacted in 1875 decreed that no child between the ages of 2 and 16 was allowed to reside in New York state poorhouses. Instead, they were removed from their guardians and placed in “Homes for the Friendless,” also run by the state.3 While ostensibly an effort to benefit the welfare of children, this law in fact tore families apart. Life at the Dutchess County poorhouse, according to contemporary Board of Supervisors Reports and newspaper accounts remained deplorable. Under pressure from the public, the county spent $60,000 to renovate the site in 1903. Apparently this effort did no good. Six years later, another New York Times article reported that “there were found inmates in what seemed a helpless and hopeless condition, lying on their beds receiving only such casual attention as could be rendered by the keeper and his wife.”4 By the 1930’s and 40’s the number of inmates at county run poorhouses was in decline. The advent of federal social security and welfare programs made the concept of a poorhouse obsolete. The function of the Dutchess County Home came to be that of an infirmary, offering care to elderly patients who could no longer live on their own. In 1938, a building was constructed on the site for the express purpose of care for the elderly and ill. In 1961, the large wing projecting from the front of the original The above information was excerpted from: Susan D. Blouse, “Early Social Welfare in Dutchess County Including the Poorhouse System,” in Dutchess County Historical Society Yearbook (Poughkeepsie, NY.: Dutchess County Historical Society Publication Committee, 1995), 10. 1 2 “A Poor-House To Be Ashamed Of,” New York Times, Dec. 15, 1878. 3 Blouse, “Early Social Welfare,” 11. 4 “Paupers Badly Neglected,” New York Times, Oct. 25, 1909. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 8 building was built to house the county mental health facilities and nursing home.5 By the 1990’s, the county closed the elder-care home at the Millbrook site. The Dutchess County Poorhouse, once home to the outcasts of society, now serves as a county run mental health center, who are arguably the outcasts of the present. Figure 3. Example of Brier Hill Cemetery grave marker. The reason behind the double numbers remains a mystery. Archival Research (Ulrich) The archival component of this project was to have provided data that would reinforce the scientific methods we were using. Owing to the absence of many primary sources, we were somewhat limited in our findings. The sources that we utilized included those kept by the county home as well as items in the possession of the Town of Washington. The poor house was required by state law to keep admittance and discharge records of its inmates. These books, along with a burial book, assorted scrapbooks and account ledgers, are presently held at Dutchess County social services. Burial permits are filed in the town in which a body is interred. These list, among other information, one’s name, date of death, and place of burial. For the Brier Hill site, the Town of Washington clerk holds the burial records. The bulk of our archival research came from the burial book kept by the poor house along with the burial permits. The scrapbooks and account ledgers, while historically interesting, did not provide us with useful information on burial practices at Brier Hill. Attempts to find information in the New York State Archives and with the Dutchess County Historical Society were in vain. It appears as if much information has been lost over time. The goal of archival research was twofold. First, many graves at the site are unmarked. There are numerous depressions in the ground, which indicate the presence of graves. However the lack of markers meant that we would need to find proof that these markers were indeed graves. Secondly, some graves are marked with numbered terracotta discs. Some appear in sequential order, while 5 Blouse, “Early Social Welfare,” 12. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 9 others do not. A few markers have two sets of numbers on them. One constant is that none of them contain names. We thus set out to find data that would allow us to connect individuals to grave markers. Our overriding goal was thus to discover the total number of graves at the Brier Hill site. Unfortunately, our archival research did not yield as many results as we had anticipated. Assisted by local genealogist Virginia (“Ginny”) Buechele, we searched through the records of the county home, hoping to find information that would prove useful to the project. Prior to the start of the class, Ginny had been abstracting data from the admittance and discharge records, which had been given to the Dutchess County historical society upon the closing of the poor house. These records covered the years 1872 through 1944. They listed names of inmates, the town from which they came, the date they entered the institution, and the date they left. When a resident of the home died, they were recorded in the discharged column as well. While these books did not provide any clue to marker numbers or burial location, they did allow us to come up with a total number of inmates who died at the poor house in these years. From 1872 to 1944, we surmised that a total of 924 deaths occurred at the poor house. While we cannot assume that all of these people were buried there, it is plausible that a large number of them were. Of great interest to our project was the burial book listing names and corresponding grave numbers. This source began in 1934 and continued through the last burial at Brier Hill, which took place in 1955. The burial book records grave numbers 607 through 748. These numbers appear in sequential order, and allow us to find out where 141 individuals are located on the site. Unfortunately, some of the markers corresponding to these years have either decayed or fell into the grave depressions. One particular marker, number 730, was the location of a man whose relatives wished to find his place of burial. Despite our search, even this relatively recent marker could not be found. A final resource that we utilized was the burial permits from the Town of Washington. The town clerk informed us that her office was in possession of these, and that we would be able to access them. The permits began to be kept by the town in 1919. We searched through each year up to 1934, pulling out the ones that listed Brier hill as the place of burial. These records gave us names and not marker numbers, however, we were able to find 105 more people who were buried at the site, although we have no way of knowing where their graves are located. Through archival research, we discovered the names of 246 people who were buried at Brier Hill. Of these, 141 have a marker number associated with them. Through scientific methods (surveying, resistivity, magnetometer, and GPR) we found approximately 838 graves. There may be more or less, although this number is not likely to vary significantly. The number of individuals who are known to be interred at the site represents 29% of the total number of graves. With the records that we were able to find, this is the extent of our knowledge derived from the archives. We have discovered everyone who was buried at the site after 1919. Their names and marker numbers, if applicable, have been recorded in our class database. Prior to this date, we have a large number of individuals who died at the county home. However, without a burial book or burial permits, there is no positive way of knowing if all of these people are at Brier Hill. Barring the discovery of additional burial books, many marked graves will exist without a name connected to them. Similarly, it cannot be proven that all individuals who died while living at the poor house before 1919 were buried there. It is obvious from the burial book that increasingly, many people were taken to private cemeteries. The large number of graves that we found on site leads one to believe, however, that many of them are in fact on the property. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 10 Methods Walkabout (Flugman). Before the official survey work commenced at Brier Hill Cemetery, the Digital Underground team made an initial walkabout or scan of the area in question, locating numerous features, and defining the boundaries of the site. This walkabout stage allowed us to become familiar with the site, and to allow our eyes to start seeing often very subtle features, and to begin to make decisions about the potential size of the cemetery, and to develop strategies on how to conduct the survey. After that first walkabout, we were able to determine as a group the best way to proceed. After that first day, we decided that it would be important for us to remain on the same page- to know what other people in the group were doing, what they were thinking, and why. To do this, we set up an electronic journal clearinghouse on a website that all team members could access. After each week, each person would submit their field notes and thoughts to the website where all others would read before the next week. Notes might include what was undertaken and completed that week, what the plan was for next week, etc. Total station (Minder). The total station is a surveying instrument used to record the location of points in the field by making very precise measures of distances and directions. It consists of a computerized unit that sits on a tripod and emits a pulse of laser light in the direction of the point of interest (Figure 4). The pulse reflects off a mirror held on a rod by a surveyor over the point and then returns to the total station. Distance is calculated by multiplying the pulse’s measured two-way travel time by the speed of light. Direction is measured by a gauge in the total station that records angle between the direction of the laser pulse and north. Distances of up to a kilometer can be measured with precision in the millimeter scale. Figure 4. Schematic diagram of total station operation. Electrical Resistivity (Brown). The electrical resistivity meter measures the ability of the soil to resist the flow of electricity. All materials contain a certain potential to carry an electrical current. However, some materials, such as ionized water, carry this current much better than other materials, such as air. Disturbed soil has more pore space than undisturbed soil, as it has been disturbed and even over Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 11 several decades will not be completely settled. If these pore spaces are filled with air, one would expect to higher resistivity than undisturbed soil. However, if these pores were filled with water, one would expect lower resistivity than undisturbed soil. Regardless if the pore space is filled with air or water, a change would be observed over a transition between undisturbed and disturbed ground. We used the resistivity meter to measure changes in the soil across the surveyed region. The instrument has four probes, the outer pair (spanning 1 m) introduce a known current into the ground (Figure 5). On the inner probes (spanning 0.5 m), the voltage difference between the two is read. - .5m 1m V Figure 5. Schematic diagram of the electrical resistivity meter. Resulting potential differences (voltages) are measured directly for each placement of the meter. The resistivity for each placement is the quotient of the measured voltage and the known current. Because the probes span a length of 1 m, the resistivity is measured over a hemisphere with a 1 m radius (A wider probe separation will sample a deeper depth). Anomalies were counted visually from an overhead picture as below. Local lows that were not near trees (associated with low resistivity) or rocks (associated with high resistivity) were considered possible graves. Magnetometry (Till). The magnetometer is used to detect differences in the magnetic signal of the soil, and also to detect any metal objects buried underground. The particular instrument used was a Geometrics G858 Cesium vapor magnetometer (Figure 6). A sensor on the end of a counter-balanced rod is connected to an electronic console that is mounted on a belt worn by the surveyor. The surveyor simply walks across the area being studied, and the instrument automatically logs the changes in the magnetic field, storing all the data in memory. The ease of use allows for large areas to be surveyed quickly, and lots of data to be collected accurately and rapidly. This instrument was an ideal choice for this project, because the Cesium sensor is the only kind of magnetometer sensitive enough to register the subtle differences in the strength of the magnetic field produced by the soil. When soil forms, particles containing metallic, or iron-bearing minerals align themselves with the earth’s magnetic field. If the soil is disturbed, the minerals are thrown out of alignment, and the strength of the magnetic field in that area is lowered. The data from the magnetometer was analyzed to find patterns of anomalies (specifically these magnetic lows) that may correspond to rows of graves. The data was also analyzed for distinct magnetic dipoles that would indicate any pieces of metal that may remain in graves, such as nails from a coffin. Magnetometer readings were taken in both a north-to-south direction and a south-to-north direction on each line that data was collected from. This helped to account for differences in the magnetic field caused by the preferential orientation of magnetic minerals in the soil. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 12 Figure 6. Nate Brown carefully moves across uneven ground in order to obtain accurate magnetometry results. Ground Penetrating Radar (McAdoo). Ground penetrating radar (GPR) uses high frequency radio waves (250 MHz) to image subsurface layers with changes in electrical properties. The unit we use is a Sensors and Software Noggin 250 Plus with a “Smart Cart” (Figure 7). The Smart Cart configuration has a computer (that controls the signal and records the data) along with the radar antennae (for transmitting and receiving the radio waves), an odometer wheel linked to the computer that keeps track of distance, and a digital video logger that displays the data in real time. As radio waves propagate into the ground, energy is reflected back up to the surface by boundaries that resist or conduct electromagnetic energy differently. For example, if there is a buried piece of metal in the ground, the boundary between the metal and the soil represents a significant change in electrical properties between the two materials, and a very strong radio wave will be returned to the surface. The bottom of a graveshaft also represents a subtle change in electrical properties between the undisturbed soil beneath the grave and the fill material within the grave. GPR also has the distinct advantage of being able to image variations in electrical properties at depth without much effort. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 13 Figure 7. Andrew Ulrich with the Ground Penetrating Radar. Results Walkabout (Flugman). Perhaps the most successful tool we ended up using was our eyes. What was found, initially, within the dense woods and underneath a thick layer of heavy brush and debris, was the presence, naturally and as expected, of numbered or marked grave sites. Based upon further examination and investigation this category of markers, clear evidence of graves, was quickly then subdivided and then divided again. Visually, what the team was seeing, was the presence of markers (roughly several hundred marked graves) with and without the significant depressions associated with evidence for a burial. This would be critical for the then secondary location of hundreds of unmarked depressions (graves), some of which would present clear physical evidence of a burial and others would have the slightest presence of a depression or none at all. At which time, the southwest corner of the cemetery was acknowledged as a section where no clear depressions or marked graves were present and should be set aside as a grid for more detailed study (Figure 8). The initial walkabout also turned up the presence of duplicated markers or marker numbers, an interesting fact of the cemetery, as well as the presence of double markers, marked graves with two numbers designating what appeared to be a single plot. Further exploration lead to the location of the water shed and pump house structures, the metal fence, which appeared to denote the southern end of the property line, the adjacent road, and the presence of a traditional, but seemingly out of place foot stone, which simply bore the initials LBH. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 14 Surveying (Flugman). With glimpses of the progression of the seasons swirling about, the team jumped head first into surveying the cemetery with the total station. And the process of flagging and recording every marked grave commenced in tandem. Every marked grave was surveyed, its coordinates digitally recorded. The team was gathering the raw materials that would become the 2003 map of Brier Hill Cemetery. The second and more challenging portion of the surveying project, involved the recording of the coordinates of all of the unmarked graves. In a process that went on for weeks, with seemingly no end in sight, dense brush was cleared, hundreds of unmarked graves were identified, numbered, flagged, and then finally, surveyed with the total station. Following the official surveying of grave sites, the team recorded the coordinates of various points along the parameter of the cemetery, as well as the features initially located such as the pump house and water shed structures and various points on the road. Outside SW grid (Till) Due to the large area of the cemetery as well as the extensive overgrowth covering it, a complete geophysical survey of the entire site was not practical. Rather, the area in the southwest corner was chosen as an area in which to focus attention and to perform a detailed survey. In addition to this grid, attention was given to certain rows that were marked as potential graves after a preliminary visual assessment. It was determined that the ground in these areas did not clearly indicate the presence of graves by visual assessment. To examine these areas more closely, geophysical data was gathered from these lines using the resistivity meter, the magnetometer, and the GPR (Figure 9). The data gathered from all of these rows provides evidence supporting the idea that graves do in fact exist where they were suspected. In order to address the issue of how to tell the difference between the natural variations of the geophysical properties of undisturbed soil from that of soil that had been disturbed by graves, a control was established. The control line was run with each piece of equipment on every day that survey data was collected, and the background "noise" from each day was used to normalize the data when it was compiled. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 15 Figure 8. Overview of the Brier Hill Cemetery. Yellow dots represent graves with the circular numbered markers. The green dots are the numbered markers that we were able to tie a name to. Depressions and geophysical “anomalies” suggesting graves are marked in pink. The colored box in the south west of the cemetery is an electrical resistivity grid. High resistivity is red, low resistivity in blue. Graves tend to have lower resistivity as water fills in excess pore space. The anomalies due to graves cause the subtle east-west striping of the data. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 16 3 Phase Analysis of U113-> U117 Sketchies: Magnetometry 54060 Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) 54055 54050 U113 U114 U115 U116 U117 54045 54040 54035 54030 54025 54020 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 U113 U114 U115 U116 U117 Electrical Resistivity Resistance Over Unmarked Graves 1400 U113 Resistance (Ohms) 1200 U114 U115 U116 U117 1000 800 600 400 200 0 0 1 2 3 Position (m) 4 5 6 Figure 9. An example of data from all three instruments taken over ground with suspected graves. Upper right image is the magnetometer data from a line of “sketchy” (i.e. unclear) unmarked potential graves marked U113-U117. Dips in the strength of the magnetic field correspond to regions of disturbed soil. The lower left image is the electrical resistivity, where lows in the data correspond to zones of disturbed soil with higher porosity, and the pores filled with conductive water. The right of the figure shows data from the GPR. The band of bright, subhorizontal reflectors and associated diffractions (“frowny faces”) are regions of disturbed soil and buried objects. Figure 10. Example of ground penetrating radar data from the control line outside of the cemetery where we believe there are no graves. While the data is difficult to interpret, there are no strong anomalies (hyperbolae- “frowny faces”) associated with buried objects and/or disturbed soil as seen in the area within the cemetery (see Figure 9 above). Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 17 Entire rows of unmarked graves? : The southwest corner (Minder) The presence of no distinct, and many faint depressions in the southwest corner of the survey area made it a major zone of interest for us. With only the results of our visual survey of the area we could not infer with any certainty whether this area was filled with grave plots or contained few or even none. For this reason we decided to conduct a focused geophysical survey over a 30 x 18 meter grid covering most of the southwest corner to look for evidence of possible graves. Resistivity. We collected resistivity measurements at 0.25 m intervals along 30 m north-south trending lines spaced 0.5 m apart covering the SW gird. The resulting data was processed into a grid and presented as a color-coded map view of measured resistivity (Figure 11). Areas of relatively high resistivity are show in red and low relatively low resistivity is shown in blue. Figure 11 (left) shows a sample of the resistivity lows we interpreted as graves. These anomalies are rectangular in shape with dimensions on the scale of a body (about 2 m x 0.5 m) and are evenly spaced in north trending lines (the same orientation as the known graves in the cemetery). Furthermore these lows matched up remarkably well with the observed faint depressions in the area. Anomalies were distributed across the entire grid and were found in several areas where no depressions were apparent. A count of these anomalies yielded evidence for a total of 178 unmarked graves in the southwest corner. Graves Graves Figure 11. Zoom of the Southwest resistivity grid showing local lows counted as graves (right). Red corresponds to areas of high resistivity. Blue corresponds to low resistivity. There is a regional gradient of low resistivity to the east and high resistivity to the west. The image on the left is a zoomed in area, outlining the shape and orientation of graves based on the field and resistivity data. The correspondence between the resistivity lows and the shape of the grave is remarkable. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 18 Figure 12. Three-dimensional representation of the resistivity data in the southwest grid. Red corresponds to areas of high resistivity. Blue corresponds to low resistivity. Purple dots are locations of visual depressions. Note how the location of the depressions correspond to resistivity lows (troughs). Magnetometry. We collected lines of magnetometry measurements along 30 m north-south trending lines spaced 1m apart covering the southwest grid. The resulting data was processed into a grid and presented as a color-coded map showing the recorded strength of the earth’s magnetic field (Figure 13). Results from our magnetometry survey were strikingly similar to those from resistivity. A linear pattern of rectangular anomalies is again observed with the same spacing and orientation. Large spikes in the displayed data near the ends are most likely associated with metal survey equipment located near the edge of the grid. The large spike inside the data is representative of a magnetic dipole and suggests that there may be a buried metal object at that location (possibly one of the deceased was buried with a personal effect). This data does not lend itself as well as the resistivity to counting up anomalies due to its lower spatial resolution, but the patterns it shows serve as an excellent verification of our resistivity findings. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 19 Figure 13. Magnetometer data from the SW corner of the graveyard. NNW/SSE striping is due to the survey direction, and the ENE/WSW striping represent the magnetic anomalies associated with individual graves. The region with very high magnetic field strength in the SW is due to a barbed-wire fence, but other regions of extreme magnetic field strength are likely due to buried metallic objects. Lewis B. Hubbell. In the course of this project, an interesting side project developed concerning a footstone marked “LBH” in the southeast section of the Brier Hill site. The footstone had been recorded in the 1934 map, and we found its location our first day in the field. This intriguing artifact, and the identity of LBH, became a key focus in our archival research. However, the lack of a name on the footstone made it very difficult to find out any information on the subject. A break came on the day that the headstone to LBH was discovered. While clearing away debris at the site, the class uncovered the stone in the exact location it ought to have been. It read, “My Brother, Lewis B. Hubbell, died March 14, 1874, aged 59 years” (Figure 14) Once the identity and age of LBH became known, it was possible for us to search through the archives for information on Mr. Hubbell. Despite our best efforts, the books in our possession yielded nothing. Ginny Buechele took matters into her own hands and conducted a genealogical survey on Lewis B. Hubbell. She found that Lewis was born in Dutchess County. After the death of his parents at an early age, census data indicates that he worked on local farms. At the time of his death, his only surviving sibling was one Caroline Hubbell Cole, a missionary living in China and San Francisco. Lewis spent his last days in the Dutchess County Poorhouse, and upon his death was buried at Brier Hill, presumably with one of the standard terracotta markers to record his location. We assume that Mr. Hubbell’s sister paid for the erection of his tombstone in an effort to memorialize her brother in a dignified manner. Lewis B. Hubbell’s gravestone is the only traditional one at the site. Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 20 This story, and the information that came to light as a result of the LBH footstone, proves that each and every person buried at Brier Hill has a story to tell. The people buried here, regardless of their station in life, are a part of Dutchess County history and as such, deserve to be remembered. Figure 14. Headstone (right) and footstone (left) of Lewis B. Hubbell. The photo on the right shows the writing on the headstone enhanced by baking soda. Conclusions Going into this project, we knew little more than what we could learn from the 1934 survey map. There were 242 marked graves covering an area of about ¾ of an acre. A quick walk around the graveyard shows that there are considerably more marked graves, and even more unmarked graves that can be identified by depressions in the ground. By the end of our survey, we had identified over 800 graves over a 1.5 acre site using a combination of geophysical tools, archival research and field observations. Confidence in our visual observations was bolstered by the detailed geophysical survey we completed in the SW corner of the cemetery. Evidence from our geophysical survey of the southwestern grid suggests that 178 graves are located in the region. This total represents 47 more graves than our visual survey of depressions in the area found. Figure 10 is a 3-D representation of the resistivity data with resistivity highs corresponding to “topographic” (i.e. resistivity) highs in the image. Plotted on top of the data are the locations where a surveyor found depressions in the SW grid. The graves in this area are distributed in north-south trending rows much like those in the rest of the cemetery. An entire row of graves was found by the geophysical survey that was passed over in the visual inspection of the cemetery because they lacked depressed ground. This row can be seen as the row of anomalies farthest to the east in Figure 9. The presence of over 150 unmarked graves located together in the southwestern corner of the cemetery leads us to believe that the SW corner may contain some the “missing graves” that correspond to the gap in the sequence of numbered burial markers (the 100s, 200s and 300s). It is possible that these Dutchess County Poorhouse- Brier Hill Cemetery Digital Underground Class- Vassar College Fall 2003 Page 21 burials took place during a period of time when graves in the cemetery were not being marked, or being marked with impermanent markers such as wooden crosses. The results of the survey of the Brier Hill Cemetery may be used to any number of ends. With the survey complete, the 1.5 acre site can be fenced off and set aside to maintain the integrity of the burial ground. The data we have collected may be of use to those interested in finding lost family genealogies. It also provides a baseline for those interested in studying the history of socio-economic interactions in the Mid-Hudson Valley. But whatever these results are used for, perhaps the most important finding is a piece of the region’s history that should not be forgotten.