Holly Smith

advertisement

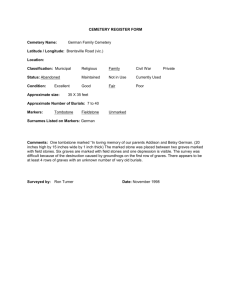

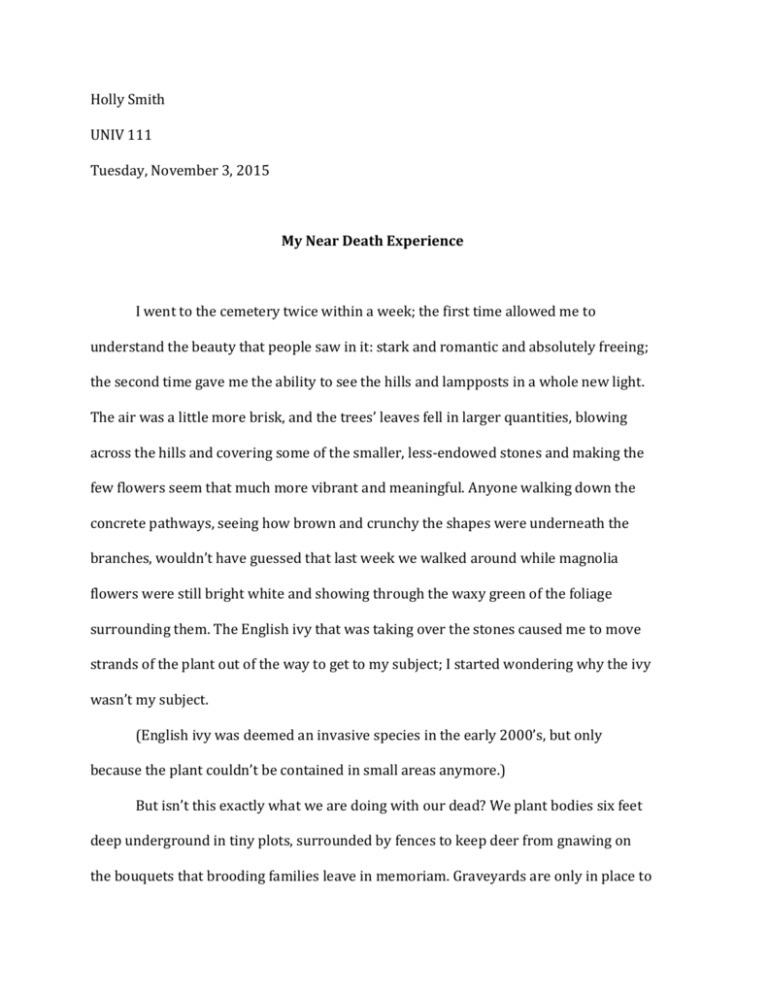

Holly Smith UNIV 111 Tuesday, November 3, 2015 My Near Death Experience I went to the cemetery twice within a week; the first time allowed me to understand the beauty that people saw in it: stark and romantic and absolutely freeing; the second time gave me the ability to see the hills and lampposts in a whole new light. The air was a little more brisk, and the trees’ leaves fell in larger quantities, blowing across the hills and covering some of the smaller, less-endowed stones and making the few flowers seem that much more vibrant and meaningful. Anyone walking down the concrete pathways, seeing how brown and crunchy the shapes were underneath the branches, wouldn’t have guessed that last week we walked around while magnolia flowers were still bright white and showing through the waxy green of the foliage surrounding them. The English ivy that was taking over the stones caused me to move strands of the plant out of the way to get to my subject; I started wondering why the ivy wasn’t my subject. (English ivy was deemed an invasive species in the early 2000’s, but only because the plant couldn’t be contained in small areas anymore.) But isn’t this exactly what we are doing with our dead? We plant bodies six feet deep underground in tiny plots, surrounded by fences to keep deer from gnawing on the bouquets that brooding families leave in memoriam. Graveyards are only in place to give the impression of what we know as the “cycle of life” having ritual and meaning. Other species find a remote area in the woods to pass away (cats, dogs, etc.), others pass on during their work schedules and another employee takes their place (as in ant colonies). The ritual that we have devised in our culture involves multiple steps and constant tending after the deceased is covered and mourned and the soil above him patted to a soft mound that will facilitate earthworms and new, natural growth. People pay for this; people pay for their loved one’s graves to be trimmed and cared for by workers who might see the cemetery as just another job on their list they get paid for. (The average cemetery caretaker makes an annual salary of just under $34,000.) Never being to a burial has desensitized me to the sights of the cemetery and I feel no connection outside of a love for the aesthetics of the graves standing out against layers of the aggressive ivy. Nature is taking over here. Here, nature was to be set and planned and paid for, but slower than the bodies fill up the empty spaces between the trees, the trees expand and cast larger shadows on the mausoleums and concrete slabs, that are shadows themselves, or echoes, of people passed. (Children that were deemed “gifted” are more likely to develop existential depression at a young age than kids with less pressure to do above average in their environments.) In the middle of the gravesite, and the construction of newer graves, was a stone with my name carved into it and delicate little holly bushes planted in the soft soil surrounding the only thing in the park that made my name seem like some kind of sick pun. “Holly” was in the same font as the hundreds of other names, and my feet were suddenly sinking into the gravel that seemed to be stable a few seconds before. I remember reading somewhere that if you tattooed the timeline of all existence, from the big bang until this very moment, onto your arm, the appearance of man as we know if wouldn’t begin until the very tip of the fingernail on your longest finger, and that filing your nail at all would mean the end to your family tree, Shakespeare, and even the discovery of the magic of fire. The tattoo that I poked into my own skin that I was afraid to let show in front of my mother, the decision to go into debt for an education, the stark realization of just how long some of the trees in front of me had been around: it didn’t matter. (“Semipermanent”: adj., long lasting, but not able to be permanent.) Life is the longest thing that any one of us will ever experience, and there is no way to get around this fact, but the opposite: “life is short,” is also true on a scale that forces someone who willingly walks through a cemetery in the harsh light of day to understand that, just as the leaves of the suffocating ivy would overtake the houses and bridges and massive water towers of any city left to its own devices, that your life as a living, breathing human who, by living, and breathing, is contributing to the growth of any plant nearby, is nothing until people who knew some of your quirks, and shared some stories with you during your lifetime, gather around a gaping man-dug hole in the earth and look down on the body that your life took form in and speak on you with wet eyes as dirt and worms are shoveled back over you and you become one with the soft growth that put the pieces in place for us to sustain ourselves in the beginning. The thousands of graves were just an easy way to arrange our losses as a collective and, as humans do, try to find meaning in the only inevitable part of life. While putting one foot in front of the other, and moving myself towards the exit, I felt as if I was floating from this “near-death” experience. The only thing to take away from noticing our trivialness as a speck in the universe is that cosmic insignificance is self-indulging, and that death rituals in any culture serve no other purpose than to prove that we actually lived. Writer’s Reflection The eventual creation that I am turning in to you is proof that first, there was craft, or my raw material. Although I also “created” the loops and the outline and so on, its purpose was to be the foundation of a larger, complete piece, thus in writing the plans, I was “crafting” my “creation.” One of the most difficult parts of this inquiry essay was forcing myself to craft raw material in a way that represented the meaning that I actually wanted to convey. Starting from the actual trip to the cemetery, I wrote lists, three loops, and three rough drafts before I decided that developing my final line wasn’t going to be any more formulated than it was in this draft. As all of this was something I had neither wrote on or thought about in a very long time, the drafting was hard but relieving in the sense that I felt as if someone wanted to listen to me speak on this subject, and when I thought of this paper as a sounding board of sorts, the words just began to flow from me and I became much more excited about the end result that was in sight. While I feel as though this paper is just long enough to get my underlying point across, I know that I could have expanded indefinitely on the idea of “meaninglessness” and the passage of time, and I did, for a bit. A draft that I wrote before this included about three extra pages of ramblings on my own feelings of insecurity about the vastness of the universe and so on. I wish that I had written in a way that didn’t sound like an old mad man that had seen too much, because I would have loved to have included some of my theories and ideas about the meaning of life. If there were another paper that I could write on the subject, I would love to, as I wanted this one to stay on topic as much as possible. Overall, I thoroughly enjoyed the challenge of writing this paper, and think that it opened me up, literature-wise, and from this point on, I believe that writing these inquiry essays will be more of a crafting process, and an easier one at that.