1 - Lancaster University

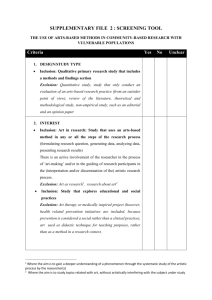

advertisement