Domestic institutions, Policy Feedbacks, and Preference Formation

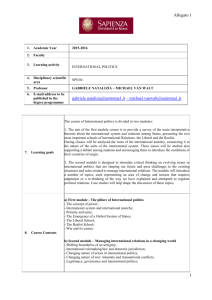

advertisement