Microsoft Word

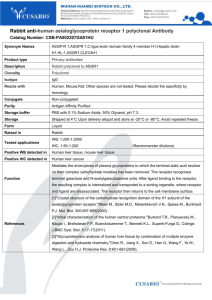

advertisement

Worm sex receptor identified by Leigh MacMillan January 17, 2003 David Greenstein quips that his group’s research can be summed up by the phrase “it takes two to tango.” The “two,” in this case, are sperm and egg, whose lively dance launches an organism’s developmental routine. Despite the importance of the sperm-egg interaction, “we don’t know at the molecular level how this works in any organism,” said Greenstein, Ph.D., associate professor of Cell & Developmental Biology. Greenstein and colleagues have now identified a sperm-sensing receptor in the eggs of a microscopic worm. Their work, reported Jan. 15 in Genes & Development, is the first to find a receptor that participates in egg maturation and ovulation. Courtesy of David Greenstein The current work is actually the second chapter of a story that started several years ago when Michael A. Miller, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Greenstein’s laboratory, began searching for the signal that lets worm eggs know it’s time to mature and be ovulated. The image shows an electron micrograph of a single sperm cell in the microscopic worm C. elegans. Major sperm protein (MSP), the signal that tells worm eggs to mature and be ovulated, appears as tiny dots In most animals, including worms and human beings, eggs are arrested in an immature state until they receive a signal to reenter the cell cycle and mature. In human beings, the trigger for this egg maturation process is unknown. In worms, it is a signaling protein released by sperm. Miller and Greenstein identified the worm maturation signal as MSP (major sperm protein) and reported their findings in Science in 2001. And now they’ve found the receptor and signaling pathway that MSP uses to promote egg maturation and ovulation. -1- Worm sex receptor identified at VUMC Greenstein hopes their research will shed light on problems with egg maturation in human beings. Conservative estimates suggest that about five percent of human pregnancies result in embryos with an extra chromosome, he said, most likely due to failures in egg maturation — specifically, failures in a cell division process called meiosis. These pregnancies usually end in miscarriage. “Human beings are really bad at meiosis,” Greenstein said. “We hope that by studying how eggs mature — meiosis — in a simple system like C. elegans (a type of microscopic worm), we will be able to glean general principles about the signals important to reproduction. We need to understand the basic biology before we can attempt to fix the problem.” Greenstein and colleagues are following a rich history of studying egg maturation as a way to discover signaling pathways that control the cell cycle and cell division, he said. “We are a bit unusual in studying C. elegans oocytes (eggs), but we’re interested in the same fundamental questions of how the oocyte makes a crucial cell cycle transition and how that is coordinated with fertilization.” Miller and Greenstein got a welcome boost in their search for the receptor that worm eggs use to “hear” the sperm signal. David Greenstein “The real breakthrough for us was the realization that there were data available that could help us,” Greenstein said, referring to the genomic studies of a group at Stanford University that defined worm egg- or sperm-enriched gene products. Miller and Greenstein narrowed the list of egg-enriched genes to a handful of candidates and used a series of biochemical and genetic tests to identify an MSP receptor. It is not the only MSP receptor, Greenstein said, and its identity — it is a so-called Eph receptor — was a surprise. Eph receptors are well characterized, and they are known to regulate multiple aspects of mammalian development, including cell migration, nerve cell connections, and vascular and heart development. They are receptors with tyrosine kinase enzyme activity and are, Greenstein said, the largest class of this type of receptor in the human genome. The first tyrosine kinase receptor, the epidermal growth factor receptor, was characterized at Vanderbilt by Nobel laureate Stanley Cohen, Ph.D. and Graham Carpenter, Ph.D., professor of Biochemistry. “Human beings are really bad at meiosis. We hope that by studying how eggs mature — meiosis — in a simple system like C. elegans, we will be able to glean general principles about the signals important to reproduction. We need to understand the basic biology before we can attempt to fix the problem.” – David Greenstein The way that MSP and its Eph receptor (a protein called VAB-1 in C. elegans) regulate egg maturation was also unexpected, Greenstein said. Instead of simply turning on a signaling pathway that tells the egg to mature, MSP actually blocks the Eph receptor. The Eph receptor, it turns out, normally acts to keep eggs in an immature state, and MSP’s block of its action stops -2- Worm sex receptor identified at VUMC this negative signaling pathway and lets maturation proceed. This type of action amounts to what’s called a “checkpoint,” Greenstein said, a surveillance mechanism that determines whether or not sperm are present. If sperm — and MSP — are around, the eggs are freed to mature and be ovulated. This kind of surveillance mechanism is especially important for the worm, because ovulation and fertilization need to be closely coupled in time, Greenstein said. “Otherwise the worms would be throwing away all of their oocytes, and that would be very bad for the species.” Checkpoints are fundamental to cell growth control, Greenstein added. Cells must pass through several important checkpoints, for example those that assess DNA damage and spindle integrity, before they can divide. “It turns out that many cancer cells are defective in checkpoints, and this leads to chromosome instability,” he said. So by studying worm reproductive signaling, Greenstein and colleagues may have identified a new checkpoint mechanism that has relevance to cancer-causing pathways. The antagonistic action of MSP at the Eph receptor is also intriguing, Greenstein said. Eph receptors are known to respond to signals called ephrins, and MSP may be the first of a group of signals that block ephrin action. “By studying sex signaling in C. elegans, we have discovered a new class of ligands for an ancient and widespread receptor signaling pathway,” Greenstein said. The team’s findings, in addition to their relevance to fundamental questions of developmental biology and cell cycle progression, could be exploited to develop new parasite-fighting drugs, Greenstein said. Nematode worms related to C. elegans are the culprits in diseases like elephantiasis and river blindness, and they destroy billions of dollars worth of crops every year. These worms share similar reproductive strategies, making MSP or proteins in the Eph receptor signaling pathway attractive targets for anti-parasite therapeutics, he said. Other authors of the Genes & Development paper include Paul J. Ruest, Mary Kosinski, and Steven K. Hanks. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, and the American Cancer Society. -3- Worm sex receptor identified at VUMC -VU- -4-

![Shark Electrosense: physiology and circuit model []](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005306781_1-34d5e86294a52e9275a69716495e2e51-300x300.png)