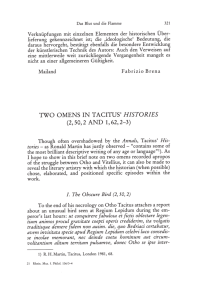

Tacitus examines Roman imperialism in terms of the

Tacitus examines Roman imperialism in terms of the negotiation of power between the Romans and their subjects. The arguments of his speakers for and against imperialism are essentially reformulations of academic polemic familiar to the ancient world. The ambivalence with which Tacitus presents imperialism reveals his indifference towards the actual view of conquered peoples which suggests that he is operating within a discourse of imperialism. Tacitus puts traditional formulations of imperialism into the mouths of Cerialis and Galcacus to explore the nature of political freedom, which is his interest .

When read in conjunction, the speeches of Cerialis

1

and Galgacus

2

are immediately reminiscent of existing Latin texts on imperialism. Ogilvie quite rightly comments that ‘Tacitus does not attempt to give arguments which Galgacus might actually have used…but contents himself with the traditional Roman criticisms of imperialism such as were voiced in the schools’ 3

. In this Tacitus was not unusual. The justifications and critiques of imperialism propounded by Roman texts

4

are substantially reproductions of the Platonic, Aristotelian and Stoic ideas believed to have been introduced to Rome by Panaetius and Posidonius

5

. The supposition that

Tacitus writes within a traditional literary framework is supported by his presentation of opposing sides of the debate through Cerialis and Galgacus. James suggests that the anti-imperial sentiment voiced by Galgacus conveys the Roman uneasiness with the injustice of imperialism ‘The concerns bestowed on Galgacus and the model of oppression he is constructing and opposing represent a Roman-style discomfort with the abuse of power’ 6 . However Tacitus’ reiteration of stock arguments makes it unlikely that he is concerned about the plight of the vanquished Gauls and Britons

7

.

Ogilvie notes that the charges Galgacus levels against the Romans are a variation on epithets found in Sallust and Velleius Paterculus 8 . Tacitus’ failure to engage with the realities of Roman imperialism betrays his ulterior motivation for looking at the

1

Tacitus, Annals, 4.73-4

2

Tacitus, Agricola, 30-2

3

Ogilvie, 1967, 253

4

e.g Cicero’s De Re Publica III.

5

Erskine, A, 1990, Chpt. 8

6

James, P, The Language of Dissent , in Huskinson, 2000, p283

7

Note the similarity between History 4..73 and Aeneid 3.35 ‘our people by defending their allies have gained domination over the whole world’.

8

Ogilvie, 1967, p257 Galgacus’ ‘raptores orbis’ are ‘latrines gentium’ and ‘raptores Italicae libertatis

relationship between the Romans and their subjects. Virgil’s Aeneid shows a true concern for the justice of Roman imperialism. Despite representing the superbus whom Rome has an imperial mission to subject, Turnus is incapable of being ruled 9 .

In contrast with Virgil’s empathic portrayal of Turnus, Tacitus’ barbarians are preoccupied with the struggle for freedom. As can be seen from Pliny, freedom was a concern and literary topos for the ancients: ‘it is Athens you go to and Sparta you rule, and to rob them of the name and shadow of freedom, which is all that now remains to them, would be an act of cruelty’ 10

. Cerialis and Galgacus are vehicles for exploring the dichotomy between liberty and subjection, rebellion and safety.

Tacitus’ primary interest in Roman imperialism is its applicability as a model to the power relationship between ruler and ruled. Throughout his works he demonstrably pursues his desire to ascertain on what terms freedom is possible for the subjects of Rome. The use of force followed by clemency in the Romans’ approach to their subjects is illustrated by the manner in which Cerialis verbal appeal to the Gauls

‘quietened and encouraged his audience, who feared harsher treatment’ 11

. Agricola follows the same policy

12

, facilitating British acquiescence to rule by increasing their dependence on the lifestyle concordant with Roman government: ‘to accustom to rest and repose through the charms of luxury a population scattered and barbarous and therefore inclined to war, Agricola gave private encouragement and public aid to the building of temples, courts of justice and dwelling-houses’

13

. Tacitus expresses his approval of Agricola’s sense of responsibility towards the newest subjects of Rome in eulogistic terms ‘Agricola, by the repression of these abuses in his very first year of lupos’ in Sallust and Vell. Pat respectively.

9

we empathise with the spirit that leaves with a groan as it ascends to Hades because, in the same way as Hamlet, Turnus is a tragic hero. His Roman virtues render him unfit to be conquered. It should be noted that the Roman mission as expressed in book six of the Aeneid ‘your task, Roman, and do not forget it, will be to govern the peoples of the world in your empire. These will be your arts - and to impose a settled pattern upon peace, to pardon the defeated and war down the proud’ (852ff), suggests that the Romans didn’t question their role as rulers of Empire. Although half of the discourse of imperialism stressed the negative implications of Empire, the other half provided the Romans with the excuse of preserving their own self-interest ‘no people would be so foolish as not to prefer to be unjust masters rather than just slaves’ (Aeneid, 3.28).

10

Pliny, letters, 8.4

11

History, 4.74

12

‘[Agricola] would allow the enemy no rest, laying waste his territory with sudden incursions, and, having sufficiently alarmed him, would then by forbearance display the allurements of peace’. Agricola,

20.

13

ibid 21

office, restored to peace its good name’ 14 . Although Agricola’s moderation is laudable, his approach is all too effective in corrupting the Gauls, who ‘were led to things which dispose to vice, the lounge, the bath, the elegant banquet. All this in their ignorance they called civilisation, when it was but a part of their servitude’ 15

. The espoused benefits of Roman rule take on a sinister light as they appear as inducements to subjection. Freedom is the cause to which Galgacus rallies the Britons. The location of Galgacus’ tribe ‘on the uttermost confines of the earth and of freedom’ 16

had previously enabled it to ‘keep even [its] eyes unpolluted by the contagion of slavery’ 17

. This conceptualisation of Roman conquest as enslavement is sustained throughout Galgacus’ speech, and is definitively realised in the choice he offers his men between fighting the Romans or submitting to ‘tribute, the mines, and all the other penalties of an enslaved people’

18

. Earlier, Galgacus had constructed the acquiescence of others to Roman rule as a futile attempt to preserve their freedom:

‘escape is vainly sought by obedience and submission’ 19

. He explores the deceptiveness of the terms used by the Romans to justify their right to rule ‘they make a solitude and call it peace’, ultimately to reveal the reality that Roman subjects lose their freedom.

Cerialis ascribes the Gauls the power of self-determination under Rome, claiming ‘You often command our legions. You rule these and other provinces. There is no privilege, no exclusion’ 20 . He suggests that dependence on one’s ruler is not a permanent concession to the arbitrary nature of despotic power: ‘There will be vices as long as there are men. But they are not perpetual, and they are compensated by occurrence of better things’ 21 . In effect, he offers peace in exchange for the Gauls’ submission to Roman hegemony ‘Let the lessons of fortune in both its forms teach you not to prefer rebellion and ruin to submission and safety’ 22 . Tacitus’ implicit question is whether peace is worth the price of servitude.

14

ibid 20

15

ibid, 21

16

ibid 30

17

ibid

18

ibid 32

19

ibid 30

20

History, 4.74

21

ibid

22

ibid

It is to be supposed that Tacitus’ interest in the impact of rule on the freedom of subjects was directly related to the way the senatorial role was circumscribed under the Roman emperors. Many scholars have remarked that the mechanisms by which

Tacitus portrays Augustus assuming power over the Roman people ‘Augustus won over the soldiers with gifts, the populace with cheap corn, and all men with the sweets of repose…the remaining nobles, the readier they were to be slaves, were raised the higher by wealth and promotion’ 23

is identical to the model of imperialism favoured by Agricola

24 . The same façade of freedom and reality of servitude applies. It seems probable that Tacitus applied the discourse of imperialism to the power relationship between the Emperor and senators of Rome because of precedents for his conceptualisation of imperialism and the lack of a traditional formulation of Roman aristocratic power.

‘Beware of Romans, even bearing gifts’ would appear to be sound advice.

Tacitus parallels the mechanisms of power by which the Emperor rules the senate and the Romans rule their subjects to reveal that freedom is the cost of government and often of peace as well. Admittedly, we have no reason to believe that Roman subjects were particularly concerned about the loss of their freedom as we suspect that rebellion resulted from more tangible deficiencies - however freedom was clearly an issue for the senators. The discourse of imperialism enabled Tacitus to represent this matter close to his heart within a structure and context to which the Romans could easily relate.

Bibliography:

Cicero, De Re Publica III, transl. C. W. Keyes, Loeb edition, 1928, Harvard

Pliny, Letters, transl.

Tacitus, The Complete Works, transl. Church & Bodribb, 1942, New York

Virgil, Aeneid, transl. J. Knight, Penguin, 1914

Erskine, A, Hellenistic Stoa, 1990, New York

Huskinson, J, Experiencing Rome: Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire,

2000, London

Ogilvie, R.O.A.M (ed.), De Vita Agricolae of Tacitus, 1967, Oxford

Woolf, G, Becoming Roman. The Origins of Provincial Civilisation in Gaul, 1998,

23

Annals, 2

24

e.g James: ‘These speeches from barbarians have a strong subtext of criticism towards the injustices and excesses of ultimate power. Their words would strike a chord with those of Tacitus’ class who periodically smarted under the loss of libertas ’. p289, The Language of Dissent , in Huskinson, 2000

Cambridge