Cry Freedom: Tacitus Annals 4.32-35

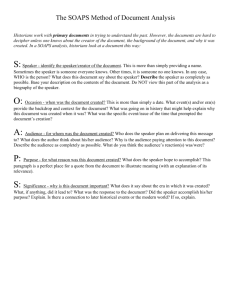

advertisement