Chapter 1: Research Context and Setting

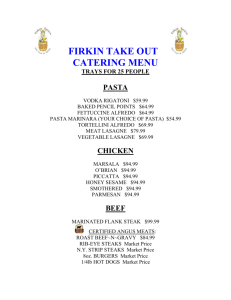

advertisement