Review Chap 1

advertisement

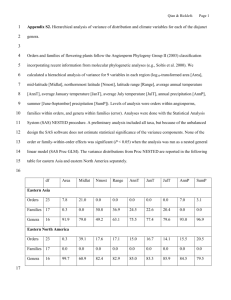

ENG 414 Typology – Review of chapters 1-3 25 January 2010 Chapter 1 (Elly) Four ways to classify language: genetic, demographic, areal, and structural/typological. What is universal in language? all languages have consonants and vowels all languages have (voiceless) stops most language use the grammatical role of subject How do we know this: study many representative languages Why are there universal: biologically innate, physiologically determined, functional Goal of typology: find patterns: differences and similarities Goal of this class: read about categories (N, V, etc), word order, and many other things. then look at languages and see what’s universal in them and what isn’t. Chapter 2 (Elly) A short chapter mainly concerned with the history of typology. Some relevant people were von Humboldt, the von Schlegel brothers, and especially Joseph Greenberg. The chapter also talks about absolute non absolute and implicational universals. Chapter 3 (Sam) Driving question: How do we go about determining language universals? Answer: Find data on languages and look at what is common across many languages. However, we cannot just look at every language, so the challenge is to have a good methodology, that is, to gather data responsibly so that we draw accurate conclusions about language universals. One was to gather data is to take a sample, but if researchers choose only sample languages with which they are familiar, their samples may be biased (Simple example: If I speak only Romance languages and so I choose Italian, Spanish, and French as my "sample" I will obviously draw unbalanced conclusions about "universal" features of language) This bias can occur to a less obvious extent in lots of research on languages. One way to get around this bias is to take samples based on language frequency. If we there are 1000 Indo-European languages and 100 Asian languages then the IndoEuropean gets 10x the representation. However, what if historically, Asian countries were just more unified, and so their languages didn't split into as many dialects? Then it's not fair to Indo-European languages to get better representation in statistics about language universals just because there are more dialects. So another way to get around bias is to take languages from different genetic origins. The main difficulty with this is that some languages may be, historically speaking, genetically different, but currently they are spoken in the same geographic area and so they have come to share certain features. Then those features are not indicative of the genetic origins from which the language came, but instead of the influence of surrounding languages in recent years (so some features could be misclassified as belonging to a genetic language group when they only became part of a language in the last few years, and because of non-genetic factors). Thirdly, Matthew Dryer tried to overcome these issues by taking a ridiculously huge sample size (over 600 languages) and classified them into genera. So in his system, languages are not individual "species" of languages, but they are species belonging to a particular genus. Then those genera were assigned to geographic areas. For a common feature of languages to count as "universal," it has to be constant within each "genus." [see page 40 for charts, statistics, and specifics]. Basically, if I understand this correctly, the genera account for genetic origins of languages, and the geographic areas divide the large genera aerially. I'm not actually sure how assigning the genera to geographic areas removes biases, it seems more like additional description than a tool to remove bias. This method seems effective, but has been criticized because most linguists cannot be familiar with hundreds of languages, and deciding how to classify languages is a matter of hot debate. Since we can't all be specialists, what about sending questionnaires to languages specialists instead of trying to work out our own data about languages with which we're not familiar? This is not a bad strategy, but sometimes language specialists are hard to contact, or too busy (or selfish, haha) to take the time to fill out a questionnaire about her or his language. Finally, the authors suggest that the most effective way to get data about a language may be to combine the two methods: That is, you get reliable data about a language by taking a sample and by contacting a language specialist to inform sample data.