Maternal Mortality in the Gambia: Contributing factors and what can

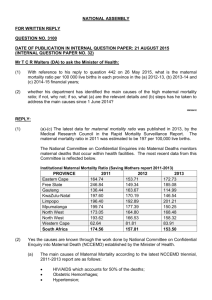

advertisement