Learning from the best 2010

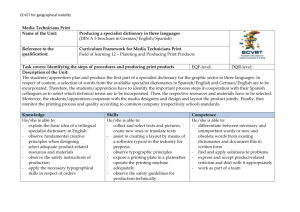

advertisement