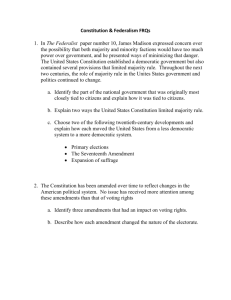

click here for unit 2 - Butler Area School District

advertisement