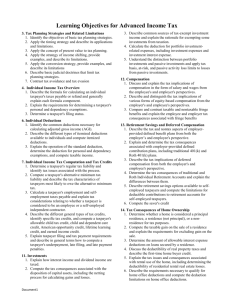

Reading 1: Introduction and Structural Overview

advertisement