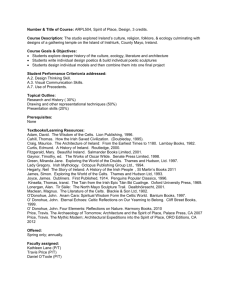

The Irish Context - Oireachtas Committee on Education and Science

advertisement