Helsinki Congress Of The International Economic

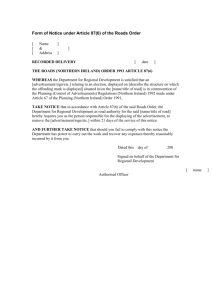

advertisement