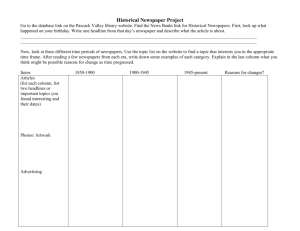

The Uses of Newspapers

advertisement