Meconium Impaction in Newborn Foals

advertisement

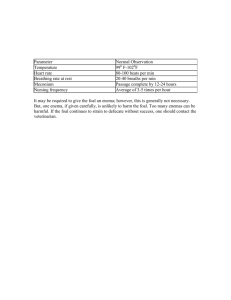

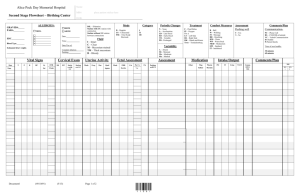

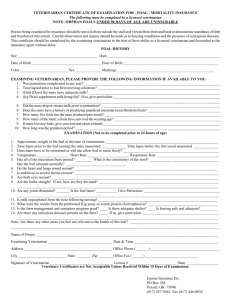

Meconium Impaction in Newborn Foals By Patrick M. McCue, DVM, Ph.D., Diplomate American College of Theriogenologists Meconium is the term used to describe the first feces or stool produced by a newborn foal. In most instances, the meconium is passed within the first three hours of life without difficulty. However, some foals cannot pass the meconium and an impaction or blockage of the intestinal tract occurs which results in severe abdominal pain. The EZ Pass enema is designed to assist foals in passing the retained meconium in foals with impactions refractory to standard medical treatments Meconium Meconium is comprised of digested amnionic fluid, gastrointestinal secretions, bile, and cellular debris that accumulate in the intestinal tract of the late-term fetus.1 It is usually dark greenish brown or black in color, firm pellets to pasty in consistency and is generally passed within the first 3 to 4 hours after birth.2,3 The average time to initial passage of meconium in 22 foals born at Colorado State University was 53 ± 35 minutes. Two additional foals did not begin to pass meconium for 5 hours, 33 minutes and 7 hours, 20 minutes, respectively. Once the meconium has completely passed, the feces of a newborn foal should change in character to a softer consistency and a lighter yellow-orange color of 'milk stool'. Colt foals reportedly have a higher incidence of meconium impactions than filly foals, possibly due to a narrower pelvic canal.4,5 Meconium impaction has been reported to be the most common cause of colic or abdominal discomfort in the newborn foal, with 1.5 % of all foals affected.6 A foal is considered to have a meconium impaction or retained meconium if frequent failed attempts to pass meconium occur within the first 12 to 36 hours of life. Failure to pass the first feces typically results in significant abdominal pain.7 A foal may also pass a small amount of meconium and still develop a meconium impaction. Therefore, continued monitoring of bowel movements over the first 24-36 hours of life is warranted. Retention of fecal material may be within the small colon at the pelvic inlet (low impaction) or higher up within the transverse or right dorsal colon (high impaction).2,3 Predisposing factors for meconium impaction include maternal malnutrition, delayed colostrum intake and subsequent loss of the laxative effect of colostrum, dystocia, prematurity, prolonged gestation, low birth weight, intestinal disease, dehydration and hypomotility of the colon.6 Clinical Signs of Meconium Impaction: Mild clinical signs are usually apparent within 6 to 24 hours after birth.2 More severe signs occur as the duration and abdominal distention increases. Impactions of the colon may be associated with more pronounced pain than impactions of the rectum. Clinical signs include: Failure to pass meconium Progressively increasing abdominal pain or colic manifested by rolling on the ground, kicking at the abdomen and swishing of the tail Depression Frequent and persistent posturing, squatting and straining to defecate (Figures 1 and 2) |ying down frequently Reluctance to suckle consistently due to repeated abdominal pain; bouts of colic may occur following nursing The urachus of some foals may re-open due as a result of straining to defecate Figure 1. Foal with meconium impaction straining to defecate. Figure 2. Foal with meconium impaction straining to defecate Diagnosis: Clinical signs Digital rectal examination with a well-lubricated finger (rectal impactions) Deep abdominal palpation Abdominal ultrasonography Contrast radiography incorporating a barium enema8 Differential Diagnosis of Abdominal Pain in Newborn Foals: Enterocolitis Colonic atresia Colon torsion Lethal White Foal Syndrome Uroperitoneum (ruptured urinary bladder) Small intestinal volvulus or intussusception Diaphragmatic hernia with bowel strangulation Other abdominal abnormalities Treatment: 1.Enema Two types of enemas are routinely used in neonatal foals to assist with passage of meconium. Perhaps the most common is administration of 100 to 133 mls (approximately 3.5 to 4.5 oz) of a commercial sodium phosphate enema (Fleet®, C.B. Fleet Co, Inc, Lynchburg, VA, or generic equivalent).2,3,9 The foal is restrained either standing or in lateral recumbency. The protective shield is removed from the enema bottle and the pre-lubricated tip is carefully inserted into the rectum. The bottle is slowly and gently squeezed to evacuate the contents into the rectum. A sodium phosphate enema should not be administered more than twice to a newborn foal within the first 24 hours of life due to the risk of hyperphosphatemia.2,5,6 An alternative is to administer an enema consisting of 500 to 1,000 mls (approximately 1 to 2 pints) of warm soapy (i.e. Ivory® Liquid, Proctor and Gamble, Cincinnati, OH) water.1,9 The soapy water enema is infused into the rectum slowly by gravity flow through a soft flexible Foley catheter. Breeding farms may choose to routinely give all newborn foals an enema within the first 1-2 hours after birth or may selectively administer enemas only to foals that do not pass meconium on their own. Either type of management strategy is acceptable. Foals that do not successfully pass meconium in the first few hours of life should be treated because of the potential for significant complications, including colic, patent urachus, failure to nurse adequately (and secondary decreased passive transfer of immunoglobulins), and colonic and/or rectal edema and inflammation. Translocation of bacteria through the inflamed colonic epithelium and the urachus (if patent) can lead to sepsis. If administration of 1 to 2 sodium phosphate or soapy water enemas is not successful in resolving a meconium impaction, administration of an acetylcysteine enema (see below) is indicated. Routine sodium phosphate or soapy water enemas may not be successful in alleviating a high meconium impaction. 2.Acetylcysteine (4 %) Retention Enema Meconium impactions refractory to traditional sodium phosphate or soapy water enemas were historically treated surgically.10,11,12 In 1990, Madigan and Goetzman first introduced the concept of treating foals with acetylcysteine for meconium impactions.13 Since that time, medical management of refractory cases of meconium impactions with acetylcysteine has largely eliminated the need for surgical intervention.5 A commercial acetylcysteine retention enema (EZ-PassTM; Animal Reproduction Systems, Chino, CA) is now available. It is recommended that this be administered to newborn foals under the advice or supervision of a veterinarian. Acetylcysteine has been reported to cleave disulfide bonds in the mucoprotein molecules of meconium, decrease the tenacity of the meconium and thus make the outer surface of the meconium slippery. Increasing the pH of the acetylcysteine solution with sodium bicarbonate increases its inherent mucolytic activity. It has been reported that the maximal effect of acetylcysteine is realized after 30-45 minutes.5 In a retrospective study of 41 cases of refractory meconium impactions treated with acetylcysteine, the average time to resolution was 11 ± 16 hours (range 1 to 96 hours) and an average of 1.5 enemas were used (range 1 to 3).5 No complications were reported with the use of 4 % acetylcysteine retention enemas for treatment of refractory meconium impaction. For administration, the foal must be restrained, either by laying him/her down on the ground or by sedation. A soft, flexible Foley catheter is inserted 1 to 2 inches into the rectum and the balloon cuff is gently inflated with no more than 30 mls of air. A volume of 125 mls (approximately 4.2 ounces) of a 4 % acetylcysteine solution is slowly infused into the rectum through the Foley catheter (Figure 3). The clamp placed on the catheter is closed and the acetylcysteine solution is allowed to remain in the rectum for 15 to 45 minutes (Figure 4).3,5 After waiting for the appropriate amount of time, the clamp is opened, the cuff of the catheter deflated and the catheter removed. The foal may then be allowed to stand or move freely (Figure 5). As noted previously, it is recommended that the foal be monitored for complete passage of the retained meconium and that observations be continued for the next 24-36 hours. The presence of yellow 'milk stool' indicates that meconium has passed completely (Figure 6) Figure 3. Administration of an acetylcysteine enema through a Foley catheter Figure 4. Foal with Foley catheter in place after receiving acetylcysteine enema Figure 5. Foal defecating following an acetylcysteine enema Figure 6. Foal with normal 'milk scours' after complete passage of meconium. Ancillary Therapy: 1.Allow foal to nurse colostrum or provide colostrum via bottle or stomach tube. Colostrum is a valuable source of antibodies required for passive transfer and has a strong laxative effect. Foals with colic associated with meconium impactions may not nurse as vigorously and may be at risk of failure of passive transfer. 2.Analgesics such as flunixin meglumine or butorphanol tartrate as needed. Caution should be used with administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. 3.Intravenous fluids as needed. 4.Mineral oil (60 to 120 mls or approximately 2 to 4 ounces) administered by nasogastric intubation to foals greater than 24 hours of age. 5.Foals with severe prolonged meconium impactions may be predisposed to sepsis. Consequently, administration of plasma and/or systemic antibiotics may be indicated. 6.Rarely, a severe refractory case of meconium impaction may require surgical intervention.10,11,12 7.Manual removal of meconium impacted in the rectum is not recommended due to the potential for injury to the rectal mucosa.3 Summary: Meconium impactions are one of the most common causes of colic in neonatal foals. It is recommended that foals be administered a sodium phosphate or warm soapy water enema within the first 3 hours after birth either routinely or if they have not yet passed meconium. Administration of an acetylcysteine retention enema is recommended for foals with refractory cases of meconium impaction. References: 1.Rossdale PD, Ricketts SW. The practice of equine stud medicine. The Williams & Wilkins Company: Baltimore, 1974, pp. 250-251. 2.Madigan JE. Manual of equine neonatal medicine. Live Oak Publishing: Woodland, CA, 1997, pp. 117-120. 3.Knottenbelt DC, Holdstock N, Madigan JE. Equine Neonatology, Medicine and Surgery. Saunders: Edinburgh. 2004; pp 249-252. 4.Martens RJ. Pediatrics. In: Equine Medicine and Surgery, 3rd edition. Mannsman RL, ES McAllister (eds). American Veterinary Publications, Santa Barbara, 1982; pp. 333-334. 5.Pusterla N, Magdesian KG, Maleski K, Spier SJ, Madigan JE. Retrospective evaluation of the use of acetylcysteine enemas in the treatment of meconium retention in foals: 44 cases (1987-2002). Equine Veterinary Education 2004;16:133-136. 6.Semrad SD, Shaftoe S. Gastrointestinal diseases of the neonatal foal. In: Robinson NE (ed), Current Therapy in Equine Medicine (3rd Edition), WB Saunders: Philadelphia, 1992, pp 445-455. 7.Bernard W. Colic in the foal. Equine Veterinary Education 2004;16:319-323. 8.Fischer AT, TY Yarbrough. Retrograde contrast radiography of the distal portions of the intestinal tract in foals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1995;207:734-737. 9.Ryan CA, LC Sanchez. Nondiarrheal disorders of the gastrointestinal tract in neonatal foals. Vet Clin Equine 2005;21:313-332. 10.Cran HR. Laparotomy in a case of retention of the meconium in a foal. Vet Rec 1980;107:47. 11.Hughes FE, HD Moll, DE Slone. Outcome of surgical correction of meconium impactions in 8 foals. J Equine Vet Sci 1996;16:172-175. 12.Vatistas NJ, JR Snyder, WD Wilson, C Drake, S Hildebrand. Surgical treatment for colic in the foal (67 cases): 1980-1992. Equine Vet J 1996;28:139-145. 13.Madigan JE, BW Goetzman. Use of acetylcysteine solution enema for meconium retention in the neonatal foal. Proc Am Assoc Equine Pract 1990;36:117-119.