English 505 Rhetorical Theory Session Four Notes Goals/Objectives

advertisement

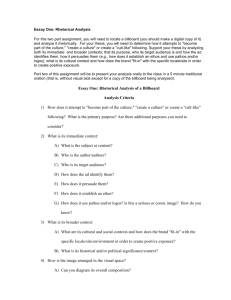

English 505 Rhetorical Theory Session Four Notes Goals/Objectives: 1) To begin to understand Aristotle’s basic understanding of Rhetoric 2) To begin to examine Aristotle’s viewpoint on Ethos and Pathos 3) To begin to understand the nature of Aristotle’s Proofs 4) To begin to understand Aristotle’s beliefs about Character 5) To begin to understand Aristotle’s beliefs about Probability 6) To begin to understand Aristotle’s beliefs about Reasoning, especially about the Enthymeme Aristotle Questions/Main Ideas (Please write these down as The son of the court physician of Macedonia to the north of Greece you think of them) As such, he was trained as a field biologist Expert at observation Aristotle Observed and described all living and non-living things And classifying such data for the use of others Unlike modern scientists, his investigations were not limited to botany or zoology Aristotle Instead, he took the whole Greek world as his laboratory Thus, we find works from Aristotle on law, political science, ethics, drama, etc. Aristotle He probably wouldn’t have seen the same distinctions we see Every subject to which Athenians turned their attention to received his diligent attention Aristotle Among these was rhetoric Earlier works on rhetoric, A maintained, dealt only with part of the field They concerned themselves with irrelevant appeals to the emotions of a jury Aristotle While neglecting reason in public discourse They (the Sophists) prescribed how a speech should be organized but ignored the speaker’s role in creating proof Aristotle Rhetoric, in A’s opinion, has an important four-fold function: 1. To uphold truth and justice and play down their opposites Aristotle 2. To teach in a way suitable to a popular audience 3. To analyze both sides of a question 4. To enable one to defend oneself Aristotle Viewed from this perspective, rhetoric is a moral but practical art grounded in probability or the contingent nature of things Aristotle A’s analytical approach to rhetoric is most apparent in his definition of the term: “The faculty of discovering in every case the available means of persuasion” Aristotle It is not enough that a speaker conceive of a single approach to persuasion He must examine all means available Aristotle Only then would he be likely to choose the best course of action (Rather than simply that which first comes to mind) (Sorry Gorgias ) Aristotle Although they weren’t codified in a systematic way until much later, the Greeks discussed each of the canons at various times Ethos and Pathos Five canons of rhetoric 1. Invention 2. Arrangement 3. Style 4. Delivery 5. Memory Ethos and Pathos Invention concerns: Finding and developing the subject of rhetoric Identifying the issues involved Creating arguments in support of the rhetor’s position Finding proof to support this position Ethos and Pathos Generally, invention is divided up into three areas: Stasis – The search for issues Proof – The support for claims Topoi – Common arguments the rhetor can summon in different situations Ethos and Pathos We’ll look at the ideas of stasis and topoi later Before we look at proof, though, let’s consider the following questions: Ethos and Pathos What does the word “character” mean to you? Where does “character” come from? What role should it play in rhetoric? Ethos and Pathos Proof: rhetoric examines persuasion and persuasion must convince its listeners Thus persuasion must use demonstrations, or proof Ethos and Pathos Aristotle apparently believed that those interested in persuasion must make ‘proof’ a part of their lifestyle Aristotle further divides proof into two categories: Atechnic (inartistic) and Entechnic (artistic) Ethos and Pathos One must use the former to invent the latter In other words, Atechnic (inartistic) proof is given by the situation and can only be used by the rhetor, not created by the rhetor Ethos and Pathos The rhetor can, however, generate three additional kinds of (Entechnic; artistic) proof Ethos – the character of the speaker Pathos – emotions Logos – the argument itself Ethos Ethos is very important because audiences judge not only the argument presented, but the speaker as well Felt that ethos always manifests itself to listeners or readers, whether a rhetor is aware or not Ethos These are proofs that rely on a rhetor’s personality or reputation Character (for ancient Greeks): the pattern of behavior or personality found in an individual or group Moral strength Ethos Self-discipline Fortitude A good reputation Some Greeks felt that a rhetor’s ability to persuade was connected to his or her moral habits Ethos Character could be invented by means of habitual practice But, it also referred to a community’s assessment of a person’s habitual practices Ethos Thus, a person’s individual character had as much to do with the community’s perception of his actions as it did with actual behavior We tend to think of character as being fairly stable Ethos They thought of character as being constructed not by what happened to the person but by the moral practices in which they habitually engaged Thus, ethos was not finally given by nature Ethos But was developed by habit (hexis) It was important, therefore, for parents and teachers not only to provide children with examples of good behavior Ethos But to insist that young persons practice habits that imprinted their characters with virtues rather than vices Since they considered characters to be shaped by practices, it was malleable Ethos (Within limits) one could become any sort of person he or she wished to be Simply by engaging in the practices that produced that sort of character Ethos It followed then that playing the roles of respectable characters enhanced one’s chances of developing a respectable character Ethos The upshot: Aristotle was not so concerned about the way that rhetors lived as he was about the appearance of character that a rhetor presented in his or her discourse (Sorry Plato ) Ethos Aristotle recognized two kinds of ethical proof: invented and situated Invented ethos – rhetors can invent a character suitable to an occasion Ethos Especially important with big audiences who would naturally not know the rhetor personally The rhetor must construct a character for themselves Ethos For A, this was especially important where the facts or arguments were in doubt People, he felt, tend to believe rhetors who either have a reputation for fair-mindedness Ethos Or who create an ethos that makes them seem fair-minded Three qualities are necessary: Phronesis – practical wisdom They must seem to be intelligent by demonstrating the they are well-informed about issues Ethos Arete –virtue They must be of good moral character They can project this image by describing themselves or others as moral persons Ethos Can refrain from the use of misleading or fallacious arguments Eunoia – good will They must possess good will toward their audiences Ethos They can do this by presenting the information and arguments that audiences require in order to understand the rhetorical situation Ethos So how can you demonstrate intelligence? You can: Use language that suggests that you are an “insider” Describe your qualifications Ethos Share an anecdote that indicates that you have experience or knowledge in a particular area Ethos How can you establish good character? You can: Weaken charges or suspicions that have been cast on your character Ethos Cite approval of your character from respected authorities (kind of like a letter of reference) Refrain from the use of unfair discursive tactics (faulty reasoning, non-representative evidence, threats, name-calling) Ethos How can you establish good will? You can: Carefully consider what listeners need to know about the issue at hand Ethos Supply any necessary information that audiences might not have at hand, but not too much (think movie review) Voice also plays a role Ethos A rhetor can use certain stylistic choices that narrow or widen the rhetorical distance between themselves and their audiences Grammatical person: I vs. she/he/it Present tense vs. past tense Ethos Qualifiers: some, most, virtually Situated Ethos Rhetoric is embedded in social context Distance: the relative social standing of participants can affect a rhetor’s persuasiveness Ethos Power: Who controls channels of communication Influences over sources of information Access to powerful people Ethos Charisma How well do the people in the rhetorical situation like each other? Aristotle also saw three possible ways in which rhetors could make ethical mistakes Ethos 1. They could be so inexperienced or so uninformed that they simply don’t draw the right conclusions Ethos 2. Even though they may know the right answer, they may hide it from audiences because of some character flaw 3. They may not care about the people they represent, so they don’t give good advice Pathos Before we turn to pathos, let’s consider the following questions: What does the word “emotion” mean to you? What role should “emotion” play in rhetoric? Pathos For ancient Greeks, pathos meant “emotion” But also “suffering” and “experience” Reason was associated with the mind Emotions with the body Pathos Aristotle believed that a speaker should know about his or her audience so as to effectively use an appeal to emotion Instead of knowing an abstract idea such as the “soul” Pathos A believed that effective speakers understood the audience’s “emotions” This is based, however, on the assumption that human beings share similar kinds of emotional responses to events Pathos For examples – mothers and fathers weep for lost sons/daughters There is the implicit assumption that people who live in the same community share similar emotional responses Pathos Therefore, he treated emotions as a way of knowing It can therefore be associated with intellectual processes rather than with bodily responses IOW, emotions hold heuristic potential (helps you discover) Pathos Aristotle believed that when people experience emotions such as anger, pity or fear, they enter new states of mind in which they see things differently (seeing something in a new light) Pathos Emotions, however, should not be confused with “appetites” (pleasure/pain) or “virtues” (justice/goodness) Pathos Aristotle argued that three questions regarding the emotions must be answered: 1. What is their state of mind? Audiences bring certain emotional states of mind to a rhetorical situation Pathos Rhetors need to decide whether this state of mind is conducive to the acceptance of their proposition If not, need to change the state of mind first Pathos 2. Against whom are the emotions directed? Who can excite these emotions? 3. For what reasons do people feel the way they do? Who/what made you angry Pathos Aristotle felt that without knowing all three of these things, it would be impossible to connect emotionally with the audience To compose pathetic proofs, you can use: Pathos Enargeia: rhetors picture events so vividly that they seem to actually be taking place before the audience’s eyes Emotion-laden words (patriot) Honorific language (gutsy) Pejorative language (flawed) Logos Revisited Aristotle taught that in each case of reasoning, the arguer began with a statement called a premise Premises were then combined with other premises in order to reach a conclusion Logos Revisited Arguers can insure that their arguments are valid (that is, correctly reasoned), if they observe formal rules or arrangements of the premises Logos Revisited Conclusions reached by this means or reasoning are only true if their premises are true In scientific demonstration, the premises of scientific argument must be able to command belief without further support Logos Revisited In dialectal reasoning, the arguers are less certain about the truth of the premises: The premises are accepted by the majority of people Logos Revisited Or by those that are supposed to be especially wise In rhetorical reasoning, premises are drawn from beliefs accepted by all, or most, members of a community Logos Revisited Many rhetorical premises are so taken for granted that they are not articulated very often These are referred to as “commonplaces” Logos Revisited The difference then between scientific, dialectal, and rhetorical premises is not the external criterion for truth But rather the degree of belief awarded to them by the people who are arguing about them Logos Revisited Greek rhetoricians called any kind of statement which predicts something about human behavior a statement of probability (eikos) Probabilities are not as reliable as certainties Logos Revisited But they are more reliable than chance They differ from mathematical probabilities in that they are both: (a) more predictable and (b) less easy to calculate Logos Revisited For example: Compare the relative probability that you will: (1) draw a winning poker hand Logos Revisited (2) to the relative probability that your parent, spouse, significant other will be upset if you come home extremely late The chances of drawing a winning hand are remote, but mathematically calculable Logos Revisited The chances that parents, spouse, significant other will be upset if you come home very late are relatively greater than drawing a winning poker hand But they can’t be calculated (too many variables) Logos Revisited The reason for the relative certainty of statements about probable human action is that human behavior in general is predictable to some extent Logos Revisited Since rhetorical statements of probability represent the common opinion of humankind, we ought to place a certain degree of trust in them Thus, statements of probability are pieces of knowledge Logos Revisited As such, they are suitable premises for rhetorical proofs For Aristotle, argument took place in language Arguers placed premises in sequence in order to determine what could be learned Logos Revisited Aristotle taught his students how to reason from knowledge which was already given to that which needed to be discovered Thus, people who wish to discover knowledge in any field did so by placing premises in useful relation to one another Logos Revisited Deduction (or reasoning) he called syllagismos (syllogisms)– A discussion in which certain things having been laid down Something other than these things necessarily result through them Logos Revisited A famous example: All people are mortal Socrates is a person Therefore, Socrates is mortal Logos Revisited The first statement is a general premise accepted by everyone This is called the major premise The second statement is a particular premise accepted by everyone Logos Revisited This premise is particular because it refers to only one person out of a class of people This is called the minor premise The reasoner has moved from a generalization to statements concerning a particular person Logos Revisited Aristotle assumed that premises did two kinds of work: (1) they named classes of things (2) and they named particulars A class was anything grouped together because of a certain likeness or common traits Logos Revisited Syllogisms worked in classical logic because they thought that the relations between classes and particulars were a fundamental element of human thinking Logos Revisited When scientists make classes or categories, they like to know that it contains all the members of the class completely Rhetors were not so concerned that the members of a class be completely enumerated Logos Revisited This is because rhetorical classes are intended to be persuasive rather than mathematical Inductive reasoning goes in the opposite direction – from particulars to universals Logos Revisited The skilled pilot is the best pilot The skilled charioteer is the best charioteer Therefore, the skilled man is the best man in any particular sphere Logos Revisited Using this logic, Aristotle invented four types of reasoning: 1) Examples – paradeigma “model” A rhetorical example is any particular which can be fitted under the heading of a class Logos Revisited It represents the distinguishing features of that class Rhetorical examples are persuasive because they are specific As such, they call up vivid memories of something the audience has experienced Logos Revisited This effect works especially well if the rhetor gives details which: Evoke sensory impressions Mention familiar sights Use sounds, smells, tastes or tactile sensations Logos Revisited Such as: Historical examples Fictional examples Analogies Logos Revisited 2) Maxims Wise sayings or proverbs which are generally accepted by the rhetor’s community Ancient maxims were often drawn from poetry or history Logos Revisited Since, in ancient times, literacy was not widespread, much of the popular wisdom was contained in oral sayings Logos Revisited 3) Signs Physical facts or real events, which usually accompany some other state of affairs For example, if someone has a fever, this is a sign of illness Logos Revisited If someone bears a scar, this is a sign of a previous injury If the relationship between the sign and the inferred state of affairs always exists, we have what Aristotle called an infallible sign (tekmerion) Logos Revisited But not all signs are infallible signs Like examples, signs can be effective if they appeal to the daily experiences that we share with members of the audience So the trick seemed to be to argue that the sign was infallible Logos Revisited 4) Enthymemes In dialectic and science, deductive arguments are called syllogisms In rhetoric, enthymemes Logos Revisited The Aristotelian distinction seems largely to be one of context In the case of syllogism - Tightly reasoned philosophical discourse In the case of the enthymeme - Popular speech or writing with resulting informality in the expression of argument Logos Revisited Derived from the word thymos “spirit” – the capacity whereby people think and feel Ancient Greeks located the thymos in the midsection of the body Logos Revisited Quite literally, an enthymematic proof was supposed to grab you in the gut Generally, major enthymematic premises represent commonsense beliefs about the way people behave Logos Revisited Rhetors ordinarily use some widely held community belief as the major premise of their argument Then they apply that premise to the particular case in which they are interested Logos Revisited An enthymeme is a type of syllogism produced in the interaction between speaker and audience The audience supplies, through its own base of information, statements that help form a speaker’s syllogism Logos Revisited In other words, when people use rhetoric, they don’t speak in tightly argued syllogisms Instead, they rely on the audience to provide some of the proof for what the speaker is saying Logos Revisited The major premises of enthymemes are probabilities concerning human action (rather than certainties as in scientific demonstration) Logos Revisited An example: Major premise: racist slurs directed against innocent people are offensive and out to be punished (notice here that not all people believe this) Logos Revisited Minor premise: John stood outside the library and shouted racist epithets at people who passed by Conclusion: John engaged in offensive behavior and ought to be punished Logos Revisited The major premise is a rhetorical probability, since it is not certain that everyone is offended by the use of racist slurs The rhetor counts on the fact that most people accept this premise Logos Revisited The enthymeme depends for its impact, therefore, on a number of community commonplaces and attitudes Enthymemes are powerful because they are based in community beliefs Logos Revisited “Members of the media should be objective” “In America, if you work hard, you’ll get ahead and make a good living” “We need nuclear weapons to prevent war” Logos Revisited “The United States must occasionally intervene in various parts of the world with military power to stop communism and promote democracy” Logos Revisited Because they are powerful, whether the reasoning is sound or not often makes little difference to the community’s acceptance of the argument Enthymemes work when listeners participate in constructing the argument Logos Revisited That is, if their prior knowledge is part of the argument, they are inclined to accept the entire argument if they are willing to accept the rhetor’s use of their common, prior knowledge Logos Revisited For this reason, enthymematic arguments do not always have to be spelled out completely The rhetor may actually purposefully omit premises or even conclusions They audience may actually enjoy supplying the missing premises Logos Revisited They may even be more readily persuaded by the argument if they have participated in its construction In modern times, the enthymeme is an abbreviated syllogism Logos Revisited That is, an argumentative statement that contains a conclusion and one of the premises, the second premise being implied Logos Revisited The essential difference is that the syllogism leads to a necessary conclusion from universally true premises But the enthymeme leads to a tentative conclusion from probable premises Logos Revisited An example: “John will fail his examination because he hasn’t studied” What is the major premise that is implied? “People who don’t study fail examinations” Logos Revisited Notice that this is only probable You can pass an examination without studying (I don’t recommend this method, however) Logos Revisited How about these? What is the missing premise? “He must be a socialist because he advocates civil rights for minority groups” “He couldn’t have killed his mother. He loved her.” Logos Revisited An actual example: “Much as he tried to obscure it, on issue after issue, my opponent showed why he earned the ranking of the most liberal member of the U. S. Senate” George W. Bush (2004) Questions? What is the unstated generalization? What is the unstated conclusion? Summary/Minute Paper: