Q&A xx - NHS Evidence Search

advertisement

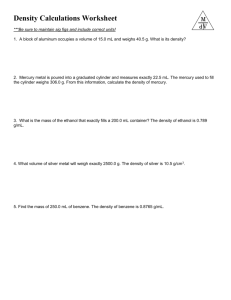

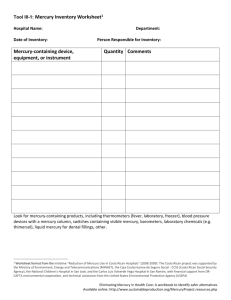

Medicines Q&As Q&A 74.4 Is it safe to have amalgam fillings placed or removed if breastfeeding? Prepared by UK Medicines Information (UKMi) pharmacists for NHS healthcare professionals July 2012 Summary Mercury is present as a contaminant in the environment from geological sources and in the food chain. Exposure to mercury also occurs through the inhalation of mercury vapour released from dental amalgam fillings. Every infant born to a mother who has amalgam fillings and/or consumes fish on a regular basis will have been exposed to mercury in-utero and will continue to be exposed to mercury via breast milk whilst being breast-fed. In-utero exposure to mercury via placental transfer is much higher than exposure via breast milk. Inorganic mercury from amalgam fillings is transferred into breast milk. However, whilst amalgam fillings do contribute to the mercury burden of the breast-fed infant, there is insufficient evidence at present to determine whether diet (organic mercury) or amalgam fillings are the main contributory factor. Little is known about the absorption of inorganic mercury by the breast-fed infant. However, one study has shown that blood levels of inorganic mercury decline after birth in infants who are breast-fed by mothers with amalgam fillings. There have been no published studies which have specifically looked at the effects of placement or removal of amalgam fillings on mercury concentrations in breast milk. There is insufficient evidence to suggest that placement and removal of amalgam fillings whilst breastfeeding increases the mercury burden of the infant in sufficient quantities to cause toxicity. If placement or removal of amalgam fillings is unavoidable whilst a mother is breastfeeding precautionary measures can be taken to minimise exposure. Background Dental amalgam is an alloy of mercury with silver and tin. It has been widely used for many years as a dental material for tooth restoration and is generally considered safe. However, there are some concerns about the level of exposure to mercury during placement, removal and polishing of amalgam fillings. Chronic exposure to a small continuous dose of mercury due to amalgam corrosion products also occurs [1]. The potential toxicity of mercury is of particular concern in women and their offspring both during pregnancy and whilst breastfeeding. In 1998 the Department of Health issued advice on dental amalgam fillings in pregnancy. This advice followed a statement from the Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment (COT) which concluded that there was no risk of systemic toxicity from dental amalgam, but as a precautionary measure advised that it may be prudent to avoid, where clinically reasonable, the placement or removal of amalgam fillings during pregnancy until appropriate research data are available [2,3]. COT did not give any equivalent advice for breastfeeding women. The question therefore arises about the safety of placement or removal of dental amalgam fillings in women who are breastfeeding and is addressed in this Q&A. From the National electronic Library for Medicines www.nelm.nhs.uk Answer Mercury toxicity Mercury is present as a contaminant in the environment from geological sources and in the food chain. It exists in a variety of chemical forms – inorganic, elemental and as methylmercury (organic mercury), each with its own toxicity profile. Methylmercury is the most toxic as it is lipid soluble and readily crosses the blood-brain barrier. It also readily crosses the placenta and is transferred into breast milk. Methylmercury induces toxic effects on several body systems. Its effects on the central nervous system are particularly critical especially during early development [4,5]. Exposure to methylmercury occurs through the consumption of contaminated fish. Exposure to inorganic and ionic mercury occurs through the inhalation of mercury vapour released from dental amalgam fillings and is likely to be greatest during the placement or removal of such fillings. This release is time-dependent and proportional to the surface area of the fillings. It also depends on many other factors such as tooth-brushing, gum-chewing and grinding of the teeth [6]. It is therefore very difficult to accurately measure the amount of mercury released and subsequently absorbed from amalgam fillings. Exposure limits for mercury in susceptible populations A joint expert committee of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations and the World Health Organisation (JECFA) has evaluated the toxicity of mercury on several occasions. In 2003 JECFA established a Provisional Tolerable Weekly Intake (PTWI) for methylmercury of 1.6 microgram/kg body weight in pregnant women. Any intake below this limit was considered unlikely to cause neurodevelopmental effects in the developing fetus [4]. They did not determine a PTWI for breastfeeding women. In-utero exposure to mercury via placental transfer is much higher than exposure via breast milk [7]. Using data extrapolation, COT suggests that a PTWI of 3.3 microgram/kg body weight is acceptable in breastfeeding mothers as the intake of the breast-fed infant would not exceed that of a developing fetus whose mother had an intake within the PTWI of 1.6 microgram/kg body weight [5]. No exposure limits for inorganic mercury were found. The FDA has concluded after consideration of the published data that infants are not at risk of adverse effects from breast milk of women exposed to mercury vapors from dental amalgams [8]. Mercury concentrations in breast milk in relation to amalgam fillings A number of studies have looked at mercury concentrations in breast milk in relation to amalgam fillings. Some of these studies have shown a positive correlation between mercury concentrations in breast milk and the number of maternal amalgam fillings [9 -15]. None have specifically looked at the effects of placement or removal of amalgam fillings on mercury concentrations in breast milk. When assessing the validity of these studies it is important to remember that only inorganic and ionic forms of mercury are released from amalgam fillings. It is necessary therefore to determine the speciation of mercury in human breast milk. In most published studies no distinction is made between inorganic and organic mercury, results being based on total mercury levels making it difficult to distinguish the source of the mercury exposure. A Swedish study collected information on fish consumption post-partum and the number, size and location of amalgam fillings in 30 lactating women [9]. The mean number of amalgam fillings per person was 12 (range 3 – 17). Mercury concentrations were measured in hair samples taken at delivery and blood and milk samples taken six weeks after delivery. The total mercury concentration in milk was 0.6 ± 0.4 nanogram/g (mean ± SD, range 0.1-2.0 nanogram/g). The inorganic mercury fraction in milk averaged 51% (range 16% - 78%) of total mercury. In whole blood inorganic mercury averaged 26% (range 4% - 57%) of total mercury. There was a significant correlation between the total mercury concentrations in blood and milk and the number of amalgam fillings (p=0.003 and p=0.01 respectively) and between the levels of inorganic mercury in blood and milk and the number of amalgam fillings (p=0.016 and p=0.018 respectively). A group who consumed one or two meals of fresh-water fish during the six week period after delivery had significantly higher levels of total mercury in blood (p<0.0002) compared with the group that did not consume any fresh-water fish. There were no significant differences between total levels of mercury in milk or hair between these two groups. The authors conclude that there was an efficient transfer of inorganic mercury from blood to milk and that in this population with low fish consumption mercury from amalgam fillings was the main source of mercury in milk. They also calculated the infant intake of total mercury from breast milk as From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk approximately 0.1microgram/kg body weight/day using the mean level of 0.6 nanogram/g milk and an intake of breast milk of 150g/kg body weight. A Bavarian study collected similar information in 145 lactating women [10]. This population had higher fish consumption. The mean number of amalgam fillings was 9 (range 0 – 19). The mean total mercury concentration in milk during the first week after birth was 1.37± 2.14 microgram/litre (mean ± SD, range < 0.25 – 20.3; n=116 ). Total mercury concentration in the blood was significantly correlated with fish consumption and the number of amalgam fillings. Total mercury concentration in milk at birth was significantly correlated with fish consumption and the number of amalgam fillings and surfaces treated with amalgam (p=0.0001 and p=0.0263 and p=0.0033 respectively). In the second milk sample taken two months later total mercury concentration correlated with fish consumption only. Mercury concentrations in these samples were lower than in samples taken in the first week after birth which the authors suggest was a dilution effect due to the larger volumes of milk produced. The authors conclude that mercury concentrations in breast milk are the result mainly of dietary habits. Amalgam fillings also have an influence but the added exposure from amalgam fillings is probably of minor importance. Another Bavarian study [11] looking at mercury concentrations in breast milk samples from 46 mothers used 9 formula milk samples reconstituted with mercury-free water as a comparison. In the reconstituted formula milk samples, mercury concentrations ranged between 0.4 microgram/litre and 2.5 microgram/litre (median 0.76 microgram/litre).The median mercury concentration of 46 breast milk samples taken on the second day after delivery was 0.37microgram/litre. Whilst these studies contribute to our understanding of the transfer of mercury into breast milk the results are inconclusive as to whether diet or amalgam fillings are the main contributory factor. Inorganic mercury from amalgam fillings is transferred into breast milk. In populations with low levels of fish consumption mercury from amalgam fillings may be a significant contributory factor to mercury levels in breast milk. Transfer of mercury to the breast-fed infant One study [12] has attempted to clarify the transfer of methylmercury and inorganic mercury during breast-feeding and infant exposure through breast milk. Twenty women were recruited to the study at delivery. Blood samples were collected from mothers and infants (n=20) at the time of delivery, at approximately 4 days, and at 13 weeks after delivery. Breast milk samples were taken at 4 days, 6 weeks and 13 weeks after delivery (n=15). Information on fish consumption, vaccinations and dental care were collected by questionnaire. A dentist recorded the number of amalgam-filled surfaces. Total mercury concentrations in breast milk at 13 weeks correlated significantly with maternal blood inorganic mercury (p=0.006) and infant blood methylmercury (p=0.01) but not infant blood inorganic mercury or maternal blood methylmercury. Infant blood inorganic mercury concentrations declined from birth to 13 weeks of age. The authors state that these results raise the question as to what extent inorganic mercury in breast milk is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract in the infant . Neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants exposed to mercury in breast milk Data relating to neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants exposed to mercury in breast milk come from two poisoning incidents in Japan and Iraq involving mercury-contaminated food, and epidemiological studies of populations with high fish consumption i.e. methylmercury in the food chain [7]. A cohort study of 1,022 infants from the Faroe Islands, a population with high dietary fish consumption investigated milestone developments in breast-fed infants [16]. Data sufficient for analysis were obtained from 583 children. Of these, 97.4% were breast-fed for at least one month, 17.2% for two months or less and 24.5% for three months or less. Three motor milestones commonly achieved between five and twelve months of age were selected for analysis: sitting without support, crawling, and standing without support. The age at which children reached these developmental milestones was not associated with pre-natal mercury exposure, as measured by mercury concentrations in maternal hair and umbilical cord blood but was associated with mercury hair concentration in the children at 12 months. Infants who reached milestone criteria early had significantly higher mercury concentrations in hair at 12 months of age. The authors concluded that breastfeeding is associated with an advantage with regard to milestone development despite the fact that methylmercury is transferred to the child via breast milk. From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk A recent study from Brazil investigated maternal mercury exposure and neuro-motor development in breast-fed infants. Tissue-mercury concentration and neurodevelopment (Gesell Developmental Schedules) were assessed at birth and six months in 82 exclusively breast-fed infants. Significant correlation was found between maternal hair mercury and infant hair mercury at birth and six months. Most infants (74%) had normal Gesell Schedules, 26% showed neuro-motor developmental delays but only 7% had multiple delays. Mothers of infants with multiple delays had hair mercury concentrations comparable to the mothers of normally developed infants [17]. Advice for breastfeeding mothers As exposure to mercury vapour from dental amalgam is greatest during the placement or removal of amalgam fillings, it has been suggested that such procedures should be avoided during the breastfeeding period [18,19]. Whilst this may be a useful precautionary measure for non-urgent dental procedures, for mothers who continue to breastfeed their infants for long periods of time this may not be practical. There are some precautions that can be taken by the dentist which may help to minimise mercury exposure [18,20]: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Use of copious amounts of cold water irrigation during the grinding process to minimise the generation of heat which can vaporise the mercury. Use of a rubber dam to isolate the mouth from the particles. When removing old amalgams, safety glasses and high-volume aspiration are a wise precaution. Avoid spilling mercury. Waste amalgam should be stored in a screw-top bottle under old radiograph (X-ray) fixing solution. This advice has not been assessed in any large scale studies. Limitations In interpreting the above data it is important to take into account the following factors: 1) Only inorganic and ionic forms of mercury are released from amalgam fillings. It is important therefore to determine the speciation of mercury in human milk. In published studies often no distinction is made between inorganic and organic mercury, results being based on total mercury levels. 2) It is important to distinguish between pre-natal and post-natal exposure to mercury. All infants whose mothers have amalgam fillings and/or consume fish will be exposed in-utero to mercury via the placenta. 3) The studies cited have not assessed the effects of placement or removal of amalgam fillings. 4) Most studies have measured mercury levels in human milk as a source of mercury exposure in infants. However, absorption is the main indicator of toxicity. Only estimates of absorption of mercury in infants are available. Disclaimer Medicines Q&As are intended for healthcare professionals and reflect UK practice. Each Medicines Q&A relates only to the clinical scenario described. Medicines Q&As are believed to accurately reflect the medical literature at the time of writing. See NeLM for full disclaimer. References From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) 8) 9) 10) 11) 12) 13) 14) 15) 16) 17) 18) 19) 20) Chestnutt IG and Gibson J. Churchill’s pocketbook of clinical dentistry. Churchill Livingstone, London. Third Edition 2007. Pages 119-121. Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment. Statement on the toxicity of dental amalgam. December 1997. http://cot.food.gov.uk/cotstatements/cotstatementsyrs/cotstatements1997/cotstatementdentalamal gam97. Accessed 18/07/2012 Department of Health. Precautionary advice on dental amalgam fillings. 29/4/1998. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Lettersandcirculars/Professionalletters/Chiefdentaloffi cerletters/DH_4004486 Accessed 18/07/2012 Summary and conclusions of the sixty-first meeting of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. June 2003. www.who.int/foodsafety/chem/jecfa/summaries/en/index.html Accessed 18/07/2012 Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment (COT) Updated COT statement on a survey of mercury in fish and shellfish. December 2003. http://cot.food.gov.uk/cotstatements/cotstatementsyrs/cotstatements2003/cotmercurystatement Accessed 18/07/2012. Jones DW. Exposure or absorption and the crucial question of limits for mercury. J Can Dent Assoc 1999; 65: 42-46. Dorea JG. Review article. Mercury and lead during breast-feeding. Br J Nutrition 2004; 92: 21-40. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Guidance for industry and FDA staff. Class II special controls guidance document: Dental amalgam, mercury, and amalgam alloy. July 2009. www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm073311.ht m Accessed 18/07/2012 Oskarsson A, Schütz A, Skerfving S et al. Total and inorganic mercury in breast milk and blood in relation to fish consumption and amalgam fillings in lactating women. Arch Environ Health 1996; 51 (3): 234-241. Drexler H and Schaller KH. The mercury concentration in breast milk resulting from amalgam fillings and dietary habits. Environ Res 1998; 77 (2): 124-129. Drasch G, Aigner S, Roider G et al. Mercury in human colostrum and early breast milk. Its dependence on dental amalgam and other factors. J Trace Elements Med Biol 1998; 12: 23-27. Björnberg KA, Vahter M, Berglund B et al. Transport of methylmercury and inorganic mercury to the fetus and breast-fed infant. Environ Health Perspect 2005; 113: 1381-1385. Da Costa SL, Malm O, Dorea JG. Breast-milk mercury concentrations and amalgam surface in mothers from Brasília, Brazil. Biol Trace Element Res 2005; 106: 145-151. Vimy MJ, Hooper DE, King WW et al. Mercury from maternal “silver” tooth fillings in sheep and human breast milk. A source of neonatal exposure. Biol Trace Element Res 1997; 56: 143-152 Norouzi E, Bahramifar N and Ghasempouri SM. Effect of teeth amalgam on mercury levels in the colostrums human milk in Lenjan. Environ Monit Assess 2012; 184: 375-380. Grandjean P, Weihe P, White RF. Milestone development in infants exposed to methylmercury from human milk. Neurotoxicology 1995; 16: 27-34. Marques RC, D́orea JG, Bastos WR et al. Maternal mercury exposure and neuro-motor development in breastfed infants from Porto Velho (Amazon), Brazil. Int J Hyg Environ-Health 2007; 210: 51-60. Hale TW. Medications and mother’s milk. Hale Publishing. USA. Fourteenth Edition 2010. Pages 653-654. Schaefer C. Drugs during pregnancy and lactation. Elsevier. London. Second Edition 2007. Pages 816-817. Mitchell DA et al. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Dentistry. Oxford University Press. Oxford. Fifth Edition 2009. Pages 608-609. Quality Assurance Prepared by Lindsay Banks, Medicines Information Pharmacist, North West Medicines Information Centre, 70 Pembroke Place, Liverpool Date Prepared August 2005. Updated April 2006, April 2008, July 2010, July 2012 From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk Checked by Christine Proudlove, Director, North West Medicines Information Centre Date of check July 2012 Search strategy Embase –1974 to date MERCURY#W.DE. AND (BREAST-FEEDING#.DE. OR BREAST-MILK#DE OR INFANTFEEDING#DE OR LACTATION#W.DE.) AB=Y, H=Y, LG =EN Medline –1951 to date. MERCURY#.W.DE. AND (MILK-HUMAN#.DE. OR BREAST-FEEDING#.DE. OR LACTATIO.#W.DE). AB=Y,LG=EN,HUMAN=Y West Midlands Medicines Information Centre – specialist file holder: Drugs in lactation. Websites accessed: The Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment at http://cot.food.gov.uk/ Accessed 21/06/2012. Department of Health at www.dh.gov.uk. Accessed 21/06/2012. World Health Organisation, The International Programme on Chemical safety (IPCS) at www.who.int/ipcs/food/jecfa/summaries . Accessed 21/06/2012 US Food and Drug Administration at www.fda.gov/ . Accessed 21/06/2012 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at www.cdc.gov/. Accessed 21/06/2012 From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk