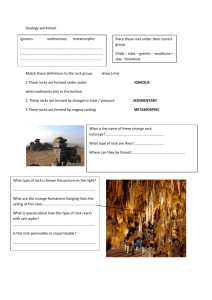

Heres an Activity about the Rock Cycle!

advertisement

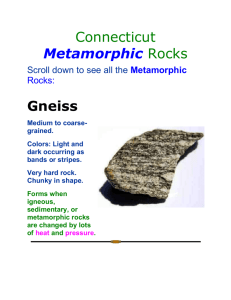

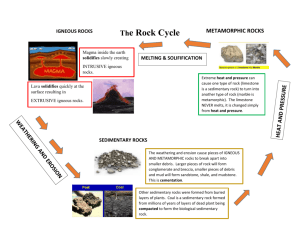

The Rock Cycle Authors: Godfrey Nowlan, GSC Beverly Ross, Rundle College Junior High School Objectives: 1. 2. 3. 4. To demonstrate the relationships between rocks. To provide some insight into the classification of rocks. To classify a collection of rocks provided by the teacher or students. To examine the relationships between sediments and rocks. Background Information: Rocks and their derivatives, sediments, form a hard outer shell on our planet known as the crust. All the rocks making up the crust fit into a simple threefold classification: sedimentary, igneous and metamorphic. The erosional products of all rocks are called sediments. The Rock Cycle diagram shows the simple relationships between rocks and sediments and the processes involved in their formation and destruction. Within each of the major rock groups there are numerous divisions and subdivisions so that sedimentary rocks may be divided by grain size into shales, siltstones, sandstones or conglomerates; or, depending on depositional environment, into terrestrial (on land) or marine (in the ocean). Terrestrial sedimentary rocks may be further subdivided by depositional process such as eolian (wind), fluvial (river), glacial, lacustrine (lake), etc, etc. Igneous rocks may be divided by method of emplacement into intrusive (within the earth) or extrusive (at the surface) or by general chemistry into acidic (high in silica) and basic (high in iron and magnesium minerals), etc. Metamorphic rocks, which are those formed through the alteration of sedimentary or igneous rocks, may be divided according to the origin of the original rock, for example metasediment, or metavolcanic. They may also be subdivided according to the degree of metamorphism. For example a slate is a low grade metasediment formed from a shale. A garnet-mica schist is a medium grade metamorphic rock formed from a shale, etc. Note that the end product of the metamorphic cycle, which occursdeep in the crust, is the transformation to a molten state called magma which is the source of igneous rocks. Materials: A pre-identified collection of rocks to use as a standard, or, better still, a person with some geological training. An assortment of rocks collected from a variety of locations. Avoid beach rocks as the polished surfaces make it difficult to see the internal characteristics. Also avoid minerals such as quartz (often found as white veins), or crystals of any mineral. An assortment of sediments derived from different locations. A magnifying glass. Method: Examine all the rocks for colour, density, texture, hardness, etc. and try to arrange by major rock type. Use freshy broken surfaces where ever possible. Use all possible criteria. A very dark, fine grained, relatively soft or lower density rock may be a shale or slate whereas a dark, fine grained, hard, dense rock may be a basalt (igneous). If you have a pre-identified collection (or an expert) check your classification. How many subdivisions do you recognize? Then examine the sediments you have collected. Arrange them by grain size (from mud through gravel). Note where they were gathered. Can you show a relationship between grain size and depositional environment, eg. muds from ponds or lakes where water flow is slow; sands from streams or beaches where water movement or wave action is moderate; and gravels from rivers or beaches where water movement or wave action is strong? Can you see the relationship between sediments and sedimentary rocks? Can you tell from the composition of the sediment and its location which type of rock it was eroded from? The Rock Cycle