TOS_sunset - Northern Woodlands Magazine

advertisement

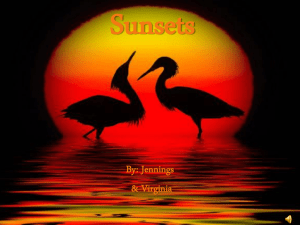

The Outside Story Title: Now’s a Good Time to Ride Off into the Sunset Author: Meghan Oliver Word Count: 690 It seems each autumn, I start noticing sunsets more. They are so pink, so orange, so bright. I’ve always chalked up my autumnal sunset attention to my mood shifting with the changing season; perhaps I’m feeling a little wistful at summer’s end and reflecting on nature’s splendor more than usual. But according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the colors we see during sunsets really are more vibrant in fall and winter than they are in spring and summer – seasonal melancholia has got nothing to do with it. The intensity of sunset and sunrise colors has to do with Rayleigh scattering. I spoke with meteorologist Chris Bouchard of the Fairbanks Museum and Planetarium in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, who kindly dropped some knowledge on this scattering business. Bouchard started off by explaining that the light we receive from the sun here on Earth is white – meaning it is composed of an even mix of all visible colors. But this white light is transformed as it passes through our atmosphere and encounters nitrogen and oxygen molecules, which causes the light beams to “scatter,” or change direction. It is this scattering that “paints the sky with color,” Bouchard explained. “Because of some fairly complex physics, these gases cause light beams of shorter wavelengths to scatter more than those of longer wavelengths.” Light beams of shorter wavelengths include violet, blue, and green; those with longer wavelengths include red, orange, and yellow. “Violet has the shortest wavelength in the visible spectrum, and so it scatters the most,” Bouchard said. Which begs the question, why isn’t our sky violet then, and not blue? “Well, in fact it is!” said Bouchard. “It’s just that the human eye is more sensitive to blue light than purple, so the sky appears blue.” At high noon, when the sun is directly overhead, the direct sunlight travels through a relatively small amount of air to reach your eye. During sunrise and sunset, the sun’s direct light comes in at an angle, which means that it has to travel through much more air than at noon, explained Bouchard. “Therefore, more cool colors are scattered away from the light beam, causing the tint of what’s left of the beam to shift strongly toward the warm end of the scale, causing oranges and reds.” What accounts for sunsets being more stunning in autumn and winter, as opposed to spring and summer? Pollution. Though, if you grew up thinking (as I did) that more car exhaust and smokestack spewage meant better sunset colors, you’ve got it backwards… for the most part. “The truth is that tropospheric aerosols [that’s pollution] … do not enhance sky colors, they subdue them. Clean air is, in fact, the main ingredient common to brightly colored sunrises and sunsets,” states NOAA’s website. The particulates of atmospheric pollution (like dust, smoke, and vehicle exhaust) are much larger than molecules of gas (like oxygen and nitrogen), making them poor Rayleigh scatterers of color. “In other words, they scatter all colors fairly evenly, much like a fog does,” said Bouchard. “Since most air pollution sources are at ground level, particulates tend to collect in the lower atmosphere. Bright sunset colors passing through these hazes tend to be muted and dulled as a result.” However, while pollution has a dulling effect on the intensity of colored light, the smog itself can become saturated with that colored light, expanding the coloration of the sunset. During our summers, particulate concentrations peak because a) winds are lightest, and b) the sun is strongest, which contributes to faster photochemical smog production. Photochemical smog develops when primary pollutants (oxides of nitrogen and volatile organic compounds created from fossil fuel combustion) interact with each other under the influence of sunlight, producing a mixture of different and hazardous chemicals known as secondary pollutants. “In the colder months, winds stir with more fervor, leading to less concentrated pollutants,” Bouchard explained. “Photochemical pollutants are also at a minimum because of the low sun angle and shorter days.” So while you may not welcome the bitter cold of late autumn and winter, you can take some comfort in the seasons’ stop-dead-in-your-tracks-and-stare sunsets. Meghan Oliver is the assistant editor at Northern Woodlands magazine. The illustration for this column was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: wellborn@nhcf.org