what is science and why popularise it

advertisement

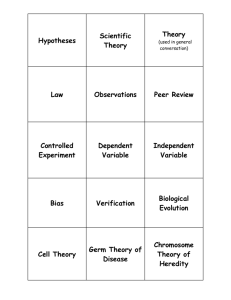

WHAT IS SCIENCE AND WHY POPULARISE IT ? Let us deal with the first question first and try the following answer : "Science is what scientists do". If so, then we are compelled to conclude that science is sometimes unscientific. For example, this writer knows a larger number of professional scientists who genuinely believe that the ×iracles (whose accounts abound in the religious scriptures ) described in the religion of their affiliation actually took place. (These same scientists usually also scoff at the miracles of religions other than their own). Miracles, by definition, violate the laws of science. One cannot simultaneously believe in the law of conservation of matter and the biblical miracle of the loaves and fishes, or the feats of the Sathya Sai Baba. Moreover, "What scientists do" is usually rather complicated and technical. If this is all that science is about , then science can never become popular .The first answer we tried is too narrow, as well as too broad. In this article, we use the term 'science' in a very different sense. We use as our answer to the first question, a definition provided by the famous physicist Richard Feynman : "Science is a long history of learning how not to fool ourselves". In this sense, science is not always complicated and technical. But it is always sceptical and critical. It is always in a state of trying to question and refute. It accepts no "truth" as final. As Einstein put it : "In the most favorable cases it says 'Maybe', and in the great majority of cases simply "No".If an experiment agrees with a theory it means for the latter "Maybe", and if it does not agree it means "No". Probably every theory will someday experience its "No"- most theories, soon after conception." We use the term 'science' as a particular way of approaching questions of validity. In science, there is never certainty. There are only increasing or decreasing levels of confidence. Or putting it in another way, decreasing or increasing levels of uncertainty and disbelief. Since science is based on systematic disbelief, it is inherently opposed to all varieties of fundamentalism- which may be described as unquestioning belief in some variety of scripture. In our country many varieties of religious fundamentalism influence both the common people and even some intellectuals . And fundamentalism of a non religious variety is also quite common especially among some other intellectuals. We have now arrived at one answer to the second question raised in the title of this article : "It is important, or necessary, to popularise science in order to counter the growth of fundamentalist tendencies in our country." This, of course, will be recognised as a political statement. Which raises yet another question : How can science be political ? Can science be political and still remain science ? It is commonly believed that science and politics have nothing in common. Many scientists pride themselves in being apolitical. Which brings us right back to the first question : "What is science?". Science, as we have seen, is a method of arriving at more or less reliable conclusions about reality. Are there areas of reality which are scientific and others which are not ? Is physics and chemistry scientific, while politics, economics and culture nonscientific? There are many scientists who would answer "Yes" to the above two questions. How scientific is their answer ? Science, in our schools, is still taught as a number of disparate `subjects'. Perhaps the single most important scientific achievement of the twentieth century is the discovery that all these different subjects are only bits and pieces of a single story. The name of that story is "The History of the Real World". The discovery of radioactivity at the end of the nineteenth century and its study during the twentieth led to the making of exceedingly powerful atomic weapons. The impact of atomic physics on the study of history has been equally, if not more powerful. The tools that it has provided have rather effectively established that everything that exists in Nature : plant, animal, earth, planet, sun and star, has come into being, has had a birth and will have a death. Everything in the real world has its history. Life and living species also have their history, including the human species. Studying anything in the real world scientifically means trying to understand the history of that thing without, as far as is possible, fooling ourselves. That there may be only one story is not an easy concept to digest. What about religion, culture and ethics ? Are they also part of this story ? The answer to this question becomes clearer if we ask a few more questions. Is there ethics on the moon ? Is there religion on Mars? What happened to our ancient cultures and eternal truths in those millions of years when there was no life on earth ? There is a growing school of researchers who are trying to understand culture and values as aspects of the real world, as aspects of human history. In this view ethics and values are the rules that societies and communities make up for themselves in order to survive. The so called `eternal' values are the ones that many different societies have found necessary for their survival and growth. History is not indifferent to values. Societies that adopt the wrong values don't survive. They destroy themselves, and with them their unsuitable values. So with the economic and political systems that societies adopt from time to time. Societies with wrong rules have short histories. Like we study the history of the atoms, the elements, the stars and the planets, the cells and the animals, the apes and the humans, we can also try to study the history of social reality. We can try to learn how not to fool ourselves while understanding what societies and communities need to survive. Reality does not divide into areas where we can learn how not to fool ourselves, and areas where we can' t. Social reality and social questions do not lie outside the domain of what can be studied scientically, outside the scope of science. Why then do so many scientists sincerely believe that areas of reality like politics, economics, ethics and values lie outside science? One reason is that many contemporary societies have a vested interest in people continuing to fool themselves on questions of social reality. One important such fool's notion is the belief that things can never be different. Poverty and inequalities have no history and in fact are eternal. Many contemporary societies attach considerable importance to keeping the methods of science strictly out of such areas. The resistance to introducing the methods of science into forbidden areas can be quite strong, as Giordano Bruno,in Italy, or the Charvakas, here in India, discovered. So an important reason why many scientists try to restrict the scope of science to strictly 'nature' , excluding 'society', is that the rules of nature are not rules which can be changed. However, the moment we begin to look at things historically with the eyes of science, we discover that the rules of societies and communities have changed in the past and are changing today. Which implies that they can be changed in future. As already stated many contemporary societies have a vested interest in people fooling themselves into believing that social rules 'are a result of human nature, and can never be changed'. Changing the rules of society, or even asserting that the rules can be changed, is never convenient, and scientists, like most people , do not like to be inconvenienced. But one consequence of modern science is hard to disagree with, even for those who shun inconvenience. Enough food is,and can be produced in our country to give everybody two square meals a day. The resources and knowledge exist to provide everybody with enough clean water for drinking and washing. The technology and resources for basic needs for all exists. Putting it differently, popularising basic needs is a real possibility today. Yet, in our country, basic needs are denied to most. Why ? This is a social question, but a question for science. The answer evidently lies in the rules that we have adopted for our country. In 1991 and thereafter, as part of the new economic policy, many rules were changed, and it was vehemently argued that the new rules were necessary 'to speed up development', Speeding up development through Liberalisation, Privatisation and Globalisation would popularise basic needs. Ten years down the results of the experiment say "No" to that hypothesis. Addressing the question of what rules really need to be adopted to universalise basic needs is probably the most important scientific question before our country today. That gives us another answer to the second question in the title. Popularising science is necessary to popularise basic needs. Countering fundamentalism and popularising basic needs are two important reasons for seeking to equip people to learn how not to fool themselves, i.e., for seeking to popularise science. Can this be done, and how ? Before discussing this question briefly, let us summarise the thrust of the previous discussion. Science is not a bunch of conclusions, but a method of trying to understand reality honestly. All aspects of reality, both natural as well as social, fall within the domain of science. The purpose of the people's science movement is to popularise the method and outlook of science among all sections of society to address certain important contemporary social needs. Which brings us to yet another definition of science,one of the most profound yet, due to the Indian mathematician and historian D.D. Kossambi : "Science is the cognition of necessity." Understanding how science can be popularised is an ongoing project. Numerous organisations in all states of the country have been working on this project for many decades. An active debate on the questions in the title of this article as well as the other questions raised in it continues within the movement. Not all participants in the movement will agree with the answers provided by this writer. One of the widest efforts is that of the Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishat. This organisation brings out a number of journals in Malayalam, including Eureka for children. It has innovated brilliantly in using local music, theatre, narrative and dance forms for communicating the questions and issues of science to the common people. Issues of science and development are now being tackled creatively through experiments involving decentralised resource mapping and planning in Kerala's villages. The KSSP was instrumental in initiating the concept of a "peoples' science movement", and in bringing together science organisations in different states for a discussion on building such a movement on a national scale. All India networks like the AIPSN (All India Peoples' Science Network) and Vigyan Prasar have emerged out of these efforts, involving literally hundreds of smaller organisations and science clubs all over the country. The role of the Central and State governments (particularly the National Council of Science and Technology Communication -NCSTC) in promoting science communication has also been significant. The Bharat Gyan Vigyan Jathas organised during the eighties led to the formation of the Bharat Gyan Vigyan Samiti which has played an important role in spreading the science movement along with the promotion of mass literacy. At the present time the movement may be described as being in a stage of deepening its roots. Its different organisations are working more intensively and extensively on their various issues of focus. At the time of writing the organisations working in the field of health are gathered in the "People's Health Assembly" at Dacca, after having conducted an extensive campaign all over the country on the key issues of health facing us in the 21st century. An important question has been why did "Health for All by the Year 00" fail ? Can we set a reasonable target for the objective "Health for All" in this century ? What is happening to health systems under the New Economic Policy . Broader questions like this of course require detailed homework on the specific issues like National Drugs Policy, or the lack of it; the impact of patent restrictions on the costs of health inputs, issues of nutrition and drinking water, new and old diseases like AIDS and TB, in both of which India holds world records. Science organisations like the Delhi Science Forum, National Working Group on Power Policy, FOSET (Forum of Scientists, Engineers and Technologists) and the Lok Vigyan Sangathana have been active in raising contemporary techno-economic issues like the burden of the Enron Project and the serious flaws in the new power policy. These issues are now squarely on the national agenda. The Enron project is a good example of how politics cannot be separated from science, and how political questions have to be tackled head-on by those serious about good science. Conventional science communication activities are an important part of the peoples' science movement. The serials "Bharat Ki Chhaap" produced by the Comet Media Foundation and Shyam Benegal's "Bharat Ek Khoj" played an important role towards the objectives of the movement. India was fortunate to have no less than three total solar eclipses which were visible from this country in the last two decades. These were used by hundreds of organisations all over the country to promote mass participation in safe eclipse viewing and in discussions on science and superstitions. The low cost solar filters produced by Navnirmiti for safe viewing ensured the participation of crores in this activity. At present the peoples science movement is building a mass campaign on studying the sun, utilising the phenomenon of sunspots, which are currently visible on the face of the sun, and which can be viewed elegantly but simply with equipment available in the poorest village school. The utilisation of low cost/ no cost methods of promoting high quality learning is both possible and necessary to counter the misconception that science is the monopoly of the advanced West, which can only be accessed through expensive computer hardware and software out of reach of most Indians, or through the National Geographic or Discovery channels on cable TV. In Caraka Samhita is contained the concise but profound statement : "Na anausadam cincit", which means: "There is nothing which is without significance for medicine". Today, we can say "There is nothing which is without significance for science." We can add as a corollary, "There is no one who cannot play a role in science." Vivek Monteiro. 4 Summary of activities : 1. Trade Union and Political Movement : a. Joined Trade Union movement in 1977 with CITU. Presently Secretary, CITU Maharashtra State Committee; General Secretary CITU, Mumbai Committee; Convenor, CITU Maharashtra State Coordination Committee for Unorganised Sector Workers. b. Co-convenor of Thekedari Padhati Virodhi Manch, a joint action committee of trade unions working on contract labour issues. Member of Central Advisory Board for Contract Labour. c. Within CITU have worked primarily on issues pertaining to contract labour, anganwadi workers, beedi workers and other issues of unorganized sector. Have also worked on the CITU writ petition opposing the Enron project and on power sector issues. d. Member of the Maharashtra State Committee of CPI(M). 2. Science Movement : a. Was an active member of Science for the People, New York, USA, and SESPA (Scientists and Enginers for Social and Political Action) while a graduate student at State University of New York , USA from 1970 -1974. Participated in the Anti-war movement there during this period, due to which became attracted to the left movement. b. Founder member of Science Education Group. Founder member of Lok Vidnyan Sangathana, Maharashtra. Active participant in all campaigns of the People's Science Movement from 1978 till now, including three total solar eclipse campaigns, sunspot campaign, bharat jan vigyan yatra, etc. c. Founder-advisor to Navnirmiti, a trust devoted to universalizing elementary science and mathematics education. Navnirmiti has innovated a number of learning toys and tools including : mathemat, navrang cube puzzle, jodo 3-d kit, very long focal length lens for sunspot projection, low cost telescope, sunspot kit, etc. NN along with other organizations like Pratimaan ,Pune is conducting full scale alternative math education programmes in many schools in Mumbai, Chandrapur, Yavatmal, and Nasik and is setting up math labs in many schools. d. Active member of Indian School of Social Sciences, Group for Nuclear Disarmament, Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament , and various coalitions working for secularism, peace, and opposing communalism. Was a joint-secretary for All India Peace and Solidarity Organisation., Mumbai. Have written numerous articles on Labour, Science, Technology, Nuclear Weapons, Energy, Power Sector, Enron and education in many newspapers, magazines and journals. Education : BSc. Physics from Bombay University 1968. M.S. from California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California 1970. Ph.D. from State University of New york, Stony Brook, USA in 1974.