To what extent is Moore`s Open Question Argument successful

advertisement

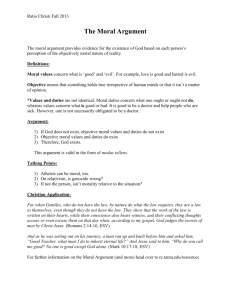

1 Harriet Johnson 76946 To what extent is Moore’s Open Question Argument successful against Ethical Naturalism? Moore’s Open Question Argument is directed at the premise of Ethical Naturalism which states that moral properties are identical with, or reducible to natural properties. Natural properties being the subject matter of the natural sciences and psychology. He is concerned with attempts to define ‘good’ as a property synonymous with an equivalent natural property, or in fact a non-natural property given his attack is focused on any attempt of conceptual analysis of the property of goodness. The ethical naturalist and Moore agree that moral judgments are expressive of beliefs which are at least sometimes true given that they concern facts which are independent of the beliefs. Yet Moore denies the assertion of the ethical naturalist that the truth conditions of these moral propositions are instantiated by facts concerning natural properties in the world. He refutes analytic conceptions of ‘good’ since on his view any attempt to define “good” naturalistically or otherwise commits a fallacy. Ethical Naturalism is an appealing position to hold since it appears to ground moral propositions and belief in an observable reality, making sense of the possibility of true knowledge and expression of morality, but for Moore goodness is a simple, indefinable, unanalysable object of thought, to be apprehended intuitively. His argument is principally constituted by the claim that for any given natural property, it is sensible to ask whether an action or object with that property is in fact good. So it cannot be the case that any natural property, such as being conducive to pleasure, or producing the greatest benefit for the greatest number, is synonymous with goodness. The Open Question argument proceeds from the supposition that the predicate ‘good’ be synonymous with natural predicate ‘n’, (from now on n will stand for this arbitrary natural predicate supposed to be synonymous with good), it follows from this that the claim ‘x is n’ means ‘x is good’, but according to Moore it is always an open question whether an x that is n is good. For example, for a hedonist the property ‘good’ is equated with the natural property of pleasure, but it is reasonable to ask whether a particular pleasurable action is good; so it cannot be the case that any natural property is synonymous with goodness. Any attempt at definition leaves such an open question. So the property of being good cannot as a matter of conceptual necessity be identical to a naturalistic property. Thus for Moore, all 2 Harriet Johnson 76946 naturalistic ethical theories are flawed because they commit what he terms, a “naturalistic fallacy”.i Moore appeals to the conviction that there is an open question; that it is reasonable to ask whether an x that is n is good, when n is taken to be synonymous with goodness. However Frankena points out that this begs the question against the Naturalist, for if the Naturalist is correct, that conviction would not be agreeable to them. Moore can only assert that it is an open question if he has already confirmed the falsity of naturalism – yet since that is Moore’s intended conclusion, he cannot employ his argument without begging the question since his premises already contain the conclusion and it is a premise that his opponent wouldn’t already share. This is only one of many well known objections to Moore’s argument, yet as Darwall, Gibbard, and Railton point out in their paper, The Open Question Argument remains compelling since it does contribute something in opposition to Naturalism; “Moore had discovered not a proof of a fallacy, but rather an argumentive device that implicitly but effectively brings to the fore certain characteristic features of 'good'-and of other normative vocabulary-that seem to stand in the way of our accepting any known naturalistic or metaphysical definition as unquestionably right, as definitions, at least when fully understood, seemingly should be.” ii Darwall, Gibbard and Railton oppose Frankena’s challenge to the Open Question Argument by expressing a central premise of Moore’s argument differently. They take his assertion that it is reasonable for any fluent, clear-minded person to ask the open question, and claim that it is plausible for such a person to hold the conviction that the question remains open, rather than making the question-begging assumption as Moore does, that it is necessarily a true conviction. They note that for a person for whom it is possible to imagine what it would be like to question whether n is good, the Open Question Argument is persuasive. This is because when the quality of goodness is ascribed to a particular action it appears to be connected with a guidance of action. They explicate this motivational content by framing the question “Is n really good?” as “Is it clear that, other things equal, we really ought to, or must, devote ourselves to bringing about n?”iii. Yet it is also possible to imagine that for any n, there could be people who were not motivated to action simply by the fact that n is supposed to be good, and so the conclusion cannot be logically drawn that n is action 3 Harriet Johnson 76946 guiding, given the imaginative possibility. And so, according to Darwall, Gibbard and Railton, it is reasonable to ask whether n is really good, and it be intelligible. Thus far Moore’s argument is successful in refuting reductive naturalism, since the challenge of question begging has been refuted and it has been demonstrated how the question can plausibly be open. So we cannot analytically establish synonymous identity between good and other natural properties. The meaning of good can be learnt synthetically through acquaintance with its many different applications. This however, remains compatible with the naturalist who holds that although ‘good’ and ‘n’ are not analytically identical, they point to the same property and can be learnt a posteriori. The naturalistic non-reductionist claims that moral properties are themselves irreducible natural properties; moral properties supervene on non-moral properties. That is to say that in each instance of good, it can be identified with non-moral, natural properties even though the reduction is not straightforward and there is no one moral property to which it can be reduced to. This view is promulgated by the Cornell Realists who employ an inference to the best explanation to conclude that since these naturalistic moral properties are required in an explanatory role it is justified to postulate such a property. So according to the Cornell Realists, moral properties are irreducible natural kinds, and since they do not claim synonymous identity between the moral and non-moral, the Open Question Argument cannot respond. Yet this argument potentially yields to a challenge of the moral sceptic; that good is identical to nothing at all, and thus is not real. Harman denies the premise of the Cornell Realists that moral properties figure ineliminably in the best explanation of experience. Through his example of a cat being torched, he explicates how we only need non-moral facts describing the action or event, and non-moral facts concerning our response to the action or event, which can be facts about our psychology, and facts about our beliefs concerning good and bad which can be explained by our conditioning including upbringing, education, and the influence of our culture. Although Harman’s Challenge to the Cornell Realists results in an undesirable moral skepticism, he does weaken the arguments of non-reductive moral naturalism, in a way that Moore is unable to by his Open Question Argument. This is not a desirable conclusion, since 4 Harriet Johnson 76946 it follows that moral judgments, and moral discourse is never justified. This is a conclusion that Moore was originally seeking to avoid in his Principia Ethica, where he clearly opposes the idea that good has no meaning whatsoever. “Whenever he thinks of “intrinsic value,” or “intrinsic worth,” or says that a thing “ought to exist,” he has before his mind the unique object—the unique property of things—that I mean by “good.” Everybody is constantly aware of this notion, although he may never become aware at all that it is different from other notions of which he is also aware.”iv So we are left with a question of what sort of a property we would have to posit to explain our moral intuitions and our moral discourse. Moore’s Open Question Argument with a little clarification has been successful in refuting reductive naturalism, but is unable to conclusively injure the non-reductionist naturalistic argument, and defeat the moral sceptic, by convincingly demonstrating the existence of non-natural moral properties. Moore articulates the omission of some quality of goodness from naturalistic understandings of moral concepts, but fails to articulate what exactly it is instead. i G. E. Moore, Principia Ethica, § 13 ¶ 2 Stephen Darwall, Allan Gibbard, Peter Railton, “Toward Fin de siècle Ethics: Some Trends”, The Philosophical Review, Vol. 101, No. 1. (1992), pp. 115-189 ii iii Darwall, Gibbard, Railton, “Toward Fin de siècle Ethics”, p.117 iv G. E. Moore, Principia Ethica, § 13 ¶ 2