April 2015 - The Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain & Ireland

advertisement

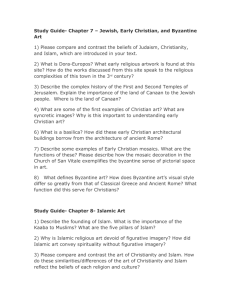

Newsletter April 2015 S pring is sprung, and that means that we’re entering the busy period for CRSBI. The first main event is the annual lecture, coming up on the 28th, and we’re making it a social event as well, both a reception afterwards as usual, and a gathering beforehand for fieldworkers so I do hope to see you there. This year’s lecture is by Prof. Tessa Garton who has recently returned to Europe after a university career largely spent in the US, and I had the good fortune to visit some of the churches she’s discussing with her a couple of years ago. One, Piasca, is a fascinating site, set in a farmyard high up in the Spanish mountains and remote from everywhere, but covered in the most spectacular Romanesque sculpture. The same sculptors also worked on sites many kilometres away and the trip through the mountain roads conveyed a very real sense of how difficult it must have been for these 12th-century artists to move materials and equipment around. Recording the sculpture is much easier than making it, which applies equally in the UK as in Spain. Two items of a formal nature can be found in the Newsletter this time, essential items on making sure we’re up to date with matters of copyright and safety. Sorting these out means that we’ve got the robust systems we need in place, should we ever have to use them, and I’ll be sending out more info soon. Meanwhile, the sunshine beckons and the lure of fieldwork is proving hard to resist, I hope you have a great season. Dr Jenny Alexander FSA CONTENTS Becoming a Fieldworker p1 Finding Woodstock Palace p3 Teamwork in Canterbury p4 CRSBI in Wales p5 Volunteering to help p6 Becoming a fieldworker I cannot believe the amazing good fortune of finding myself doing something practical in an area of personal interest that was first kindled some 30 years ago with the English Romanesque 1066-1200 exhibition at the Hayward Gallery. Being taught Romanesque and Gothic by John McNeill and Nora Courtney at Birkbeck Extra-Mural in the 1990s sustained my curiosity; while family and career took up all available hours between then and now. A chance meeting with Nora at the Westminster BAA in 2013, where she was recruiting for CRSBI volunteers, led to my finding myself in May 2014 in a rain-soaked churchyard at St Andrew's in Cobham, Surrey. Measuring; photographing by co-team member, Peter Hayes (your newsletter editor); and describing the reset and whitewashed Romanesque doorway, with three-orders of arcading; being tutored on-site by Nora; dodging church cleaners and flower ladies; it was pure bliss! Two more churches on that day in Merton and Another 15 churches visited in three days in North-west Kent seemed to make ample writing-up work for the winter break. And then came the call - Mary Berg and Toby Huitson (East Kent) wanted extra help recording the Romanesque sculpture in Canterbury Cathedral. 'WOW!! Ron Baxter came and joined our small team, providing expert analysis and guidance, as well as massive torches and an extra camera. The staff at the Cathedral could not have provided more help. Four days of intensive work and we realised there were still massive gaps in the photographic record we had created. My personal highlight was seeing the perfection of the Corona chapel from the triforium level. Then having edged my way through the narrowest of medieval passages into the wide southern triforium of the Trinity Chapel, imagine my surprise to see the two sculptures which had made such an impression on me 30 years ago at the Hayward! Thames Ditton were followed by another two visited in Cobham and Stoke d'Abernon on the May Bank Holiday rain-soaked yet again - but this intensive introduction set Peter and me on our way. So I’m looking forward to writing-up all that we have seen this season and visiting and recording more Romanesque sculpture in 2015. Susan Nettle 2 Finding Woodstock Palace M any of the stones on the interior of the Grand Bridge of Blenheim Palace at Woodstock (Oxfordshire) share a previous history. Started in 1708, work on the bridge stopped in 1712. Vanbrugh, the architect of the bridge, had envisioned a much grander crossing, with the nearby Woodstock Palace consolidated and preserved. Work on the bridge resumed in 1716. But in 1721/2 William Townsend and Bartholmew Peisley were contracted to complete the bridge. Soon it was decided that the old royal palace would be torn down and stonework from it reused in its construction. In the end, the bridge, with its charming garden rooms, was never fully completed and the lakes designed by Capability Brown in the 1760s made access to the rooms much more difficult. Watching a TV documentary about Blenheim Palace some years ago, I became aware that there were still stones to be seen on the interior of the bridge which must have come from the palace. So recently, boosted by the need to discover what survives of Romanesque sculpture for the Corpus, I asked Blenheim Palace if they would allow me access to the interiors; to my delight they did. Thus, on a sunny August day in 2014, I and my companion from the estates office, ventured down the narrow shaft which leads to the southern part of the bridge. This meant first the removal of a rather heavy slab which covered the shaft entrance (carried out by still other estate staff). Once down the hole, one quickly discovered the reason for this strange entrance. The entire original staircase had collapsed and become home to a flock of birds, nesting in the crevices of the walls. Beautifully preserved here and elsewhere were also the mummified carcasses of hundreds of butterflies, still holding tight against the wall, wings folded as if asleep. The interior of the bridge was a delightful surprise, with long corridors leading to a series of rooms, some gracefully domed. Unlike the exterior, the interior walls are rubble built, with many stones clearly reused. Which, if any, were from the palace? On this side of the bridge, the only evidence I saw came from numerous diagonally-tooled ashlars. Now it was time to visit the other side of the bridge and this meant retracing our steps upwards through the shaft and a short walk over the top to the other side. Luckily, we thought, we could gain entrance from below through a gated doorway which led to a still-intact staircase. What we had overlooked, however, was that between dry land and the doorway was a lot of mud. My ingenious companion soon noticed a short wooden ladder nearby and this became our own pontoon to the entrance. The massive ironwork, once unlocked, fell heavily down to create a somewhat dryer entry; and then we were inside. Like the 3 southern half of the bridge, there were long corridors, unfinished floorings, numerous rooms and, of course, more diagonally-tooled ashlars. Finally, in the last room, with the light shining onto it, was what I had longed to find: a section of stone with roll moulding and flanking hollow chamfer of Norman design. At last, I had found something tangible from the palace. My guide ventured off to see what else he could find and eventually settled down into one of the openings with the sun shining down on him, as I measured and photographed what had become the great discovery of the day. A hole behind the stone suggested that I might not have been the first to discover this carved stone, but for the moment it was mine to enjoy. Only one thing prevented us from reaching dry land: the iron gate and wooden ladder, both now firmly fixed into the mud. It was impossible for one person to lift the iron gate back into position and my terror of dropping my camera into the mud meant a rethink. I managed to make shore and set my equipment down, but once I returned to the rather flimsy ladder it shifted, and the mud soon began to rise. Just short of injuring ourselves after several attempts to lift the gate, we pulled all our strength together and just managed to release the gate from the mud, get it closed and locked. It was certainly an eventful day, but it was worth it. There are still a few lower rooms to visit - and the ONLY way to see these is by boat. But I’ve left this for another day. It was now time to leave. Having gathered up camera equipment and tripod it seemed our adventure was nearly over. James King Teamwork in Canterbury O n a damp Monday in October last year the Kent team (Peter, Susan, Toby and me) were joined by Ron to begin four days of recording Canterbury Cathedral. It all sounded so straightforward when applying for the special funding for the project and we were thrilled when the application was successful (our thanks to all those concerned in making it). Toby and I felt we knew the Cathedral but systematically recording it was a different prospect and all except Ron were initially daunted by the scale of the exercise. We divided the upper choir – or quire, as Canterbury calls it – into zones and allocated teams to those zones. Toby and I took the south-east triforium which we knew housed the works of the organ. What we didn’t know and cannot be seen from below is that there is immovable thick black netting along the whole length to prevent birds damaging the organ (see picture 1). There is also extensive scaffolding outside on the north side. 4 Apart from the netting, the task was fairly straightforward. The earlier Romanesque sculpture was most fun to record, interiors and exteriors. The East End beyond the actual choir area is transitional Gothic and the sculpture does not show variety from bay to bay. Ron was heard to mutter, ‘Why couldn’t they have started rebuilding this part after 1200?’ The Romanesque crypt will be part of Stage 2. cathedral staff could not have been more supportive from the most senior lay employee, Brig. John Meardon, to the volunteers everyone went out of their way to be helpful. It was not hard to avoid clashing with services or the large number of visitors but the Dean’s guinea fowl made every effort to get under feet when we were recording outside. It was fun to work together, share ideas and find solutions to problems. We took breaks to warm up and I don’t think it was because of us that the Cathedral Café closed at Christmas – we did our best! Sadly, it seems that we were all so focused on the task in hand that we took no jolly pictures of the team. Mary Berg We were not only able to record anywhere in the cathedral that we wished but we were positively encouraged to do so. The CRSBI IN WALES I n Wales, CRSBI progress is behind that in England, Ireland and Scotland and it has been difficult to recruit fieldworkers in Wales. David Robinson has provided a sound basis for future fieldwork in his recent report (The Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland: The Status of Sites in Wales, May- June 2014, Updated October 2014) featuring 280 sites. It is now proposed to re-launched CRSBI in Wales; firstly to raise the profile of the Corpus across the sector, both in terms of organisations and interested individuals, and secondly to create interest in fieldwork. A Project Coordinator is 5 currently being recruited to coordinate this work over a period of six months, which will include organising two seminars in North and South Wales, (see the website for the Job Description). Anyone interested in carrying out fieldwork in Wales is invited to register an interest via info-crsbi@kcl.ac.uk, Nigel Clubb Blind arcade at Chepstow Castle HEALTH AND SAFETY CRSBI volunteers are, of course, experienced in visiting and recording historic buildings and will be aware that there can be hazards in moving around inside historic buildings and structures and working within and outside them. CRSBI hopes that everyone working in the field will have as safe an experience as possible, by being able to identify, manage and mitigate any potential risks. For this reason, the Chair and Executive Board of CRSBI are adopting a Health and Safety Policy (which they expect to see adopted by the CRSBI team at all levels). A key element of the Policy will be a Health and Safety Guidance Note to Fieldworkers. Our Policy is developed on the basis that any action should be proportionate to the risk and in the vast majority of cases, fieldwork is no more risky than a visit by any member of the public. Nevertheless, accidents can happen and we all need to be aware of the types of risk which may arise. REVISED COPYRIGHT ARRANGEMENTS The essence of CRSBI as a project has is that volunteer fieldworkers provide their expertise and time in order to contribute their images and text as part of a Corpus of knowledge about Romanesque Sculpture to be maintained for the benefit of current and future generations. We are reviewing our copyright arrangements to enhance and protect the copyright and moral rights of fieldworkers and to give CRSBI and the ability to sustain and manage the Corpus into the future by ensuring that the CRSBI is itself licensed to publish the material. As a result of the review, we are hoping that current and past fieldworkers will be willing to sign a Copyright Agreement to cover the work they carry out for the Corpus from now on. We will also be inviting fieldworkers to agree to extend this agreement to cover work they have carried out in the past. Jenny Alexander, Chair of CRSBI, is in the process of writing to fieldworkers with more details. Nigel Clubb 6 Volunteering to help CRSBI I f you are reading this the chances are that you know the truth of the saying, ”If you want something done, ask a busy person!” Everyone who is helping us to complete this project has other commitments, academic, commercial, domestic or in the community. This as true for everyone on the Project Board and on the Sub Committee as it is for fieldworkers. Everyone who works for CRSBI is a volunteer. The small grant from the British Academy, which is our only certain funding every year, along with other contributions only allow enough for us to pay travel expenses and to give the editors, who give us the benefit of their expert knowledge of Romanesque sculpture, a small fee. The new database means that we no longer have to pay to have reports and photos uploaded, as all fieldworkers can access it directly. However to complete our survey of Romanesque sculpture we do still need more fieldworkers. As well as for Wales we need more people able to record in South Gloucestershire, Devon, Hampshire, Lancashire and Cumbria. If you think you could do even a few sites please contact me, at nora.romanesque@gmail.com. Nora Courtney The Annual Lecture will be given on Tuesday 28th April 2015 at 5.30 p.m. at the Courtauld Institute of Art Professor Tessa Garton will speak on Evidence set in stone? Twelfth-century sculptors and workshop practices in northern Palencia, Spain. Self-portrait of the sculptor Micaelis from the church of Revilla de Santullan 7