JCA 83 South Norfolk and High Suffolk Claylands

advertisement

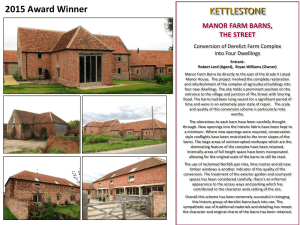

JCA 83 South Norfolk and High Suffolk Claylands. 2 JCA sub-units - 1: Clay Plateau, 2: the River Valleys. 1. Settlement and Development Iron Age and Roman settlement was extensive and grew again in the Saxon period so that by the time of Domesday most of present villages were established and the area was one of the most densely populated in England. The settlement pattern is a mixture of villages, mainly in the west and the river valleys, with numerous scattered farmsteads and hamlets set around greens displaying the process of colonisation from woodland in the medieval period. Round-towered Saxo-Norman churches are a particular feature of the area, displaying a tradition of flint construction which continued in later medieval churches. The larger market towns are small in comparison with those in adjacent areas, and retain high proportions of 15th -17th century buildings. The area has an overall very high survival, in a national context, of pre-18th century buildings, these being in timber frame and with colourwashed plaster walls. Flint and brick used from the later 17th century for vernacular buildings. Important survival of clay-lump and cob walling, predominantly of 19th century date. High survival of moats, generally associated with high-status sites and of 12-13th century date, in this area particularly near the Dive Valley around Eye and Hoxne. 2. Agriculture A mixed farming economy of arable and dairying (of particular importance in High Suffolk, until eclipsed by other areas in the 18th century) brought wealth and supported a broad spectrum of middling gentry and yeoman farmers. This stable economy did not lend itself to the changes seen elsewhere in the 19 th century, hence much of the countryside remains closely tied to the pre-industrial past - with numerous small-scale holdings and owner-occupiers, and one of the country's highest concentrations of surviving pre-1750 farm houses and barns. The tradition of timber-framed construction is exceptionally well represented in this area. A distinctive feature is the area’s combination barns. On the dairy farms of the South Norfolk and High Suffolk Claylands pre-1750 barns were typically of three bays with a central threshing floor and a fourth bay containing lofted stable or cattle accommodation. ‘Neathouses’ for housing cattle are documented and commonly survive as smaller timber-frame structures dating from the 17th century: these are locally distinctive and highly significant where they survive as rare examples of early cattle housing. This is the direct result of both the need to house dairy cattle and the reduced requirement for crop storage in these pastoral areas. Intensification of arable farming in later 18th and early 19th centuries led to removal of internal partitioning and construction of more threshing barns. High survival of pre-1750 farmstead buildings, particularly farmhouses (which can include cheese rooms) but also including medieval and later aisled barns. Larger farmsteads developed as loose courtyard complexes, and many as dispersed plan complexes, with 2 or more aisled or unaisled barns. Granaries and stables, mostly dating from the 18th century but with some notable earlier examples. As arable and requirement for yard-fed cattle increased from late 18th century, farmsteads were typically redeveloped with south-facing cattle courts. New barns were rarely built as corn was commonly stacked outside. Dispersed and loose courtyard plans are still dominant in the area. 3. Fields and boundary patterns Beneath the pattern of medieval and post-medieval holdings it is possible to perceive a landscape of much greater antiquity - the sinuous co-axial fields whose principal parallel boundaries continued mile after mile irrespective of contours. Good examples remain visible to the east of Stane Street, orientated with the Roman Road and therefore likely to be Roman or later. Elsewhere the patterns of co-axial features are less irregular and may be of still earlier origin. By the late 18th century barely 10% of the landscape remained as unenclosed pasture or common arable, the majority divided into small hedged enclosures closes, averaging as little as five acres. From the late 18th century improved drainage methods and increasing grain prices led to widespread arable conversion across the dairy lands of High Suffolk. The late 20th century saw further enlargement of arable fields, breaking down still further the patterns of irregular co-axial fields in the centre of the area and long coaxial fields to the east. Some areas of the plateau have developed a prairie-like character. 4. Trees and woodland The area historically had an abundance of woodland, both in managed lots and hedgerows, which was intensively utilised as building materials and fuel. Ancient woodland is now largely confined to small patches dotted along the river valleys. Elsewhere the wooded character is maintained by numerous standard and pollards in boundaries and parkland, by thick hedgerows and by numerous modern plantations providing shelter and shooting cover. Hedgerow oaks sometimes remain even where the hedgerows have been removed. 5. Semi-natural environments 6. River and coastal features. Pastoral farming, once the core of the area's economy, is now limited to areas such as the Waveney Valley