summary report - Faculty of Education

advertisement

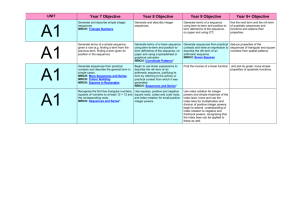

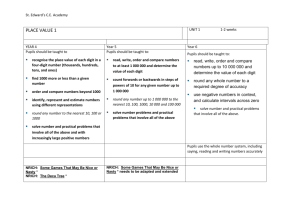

Report 18/06 Examining the role and nature of mediation that 'steps' pupils into problem solving and considering its value to an online mathematics enrichment environment Jennifer Piggott, Jennifer Green, Liz Pumfrey The NRICH project was founded in 1996 (Beardon, 2003) and is focused around a website (www.nrich.maths.org) which contains a range of resources including mathematical problems whose solutions are supplied by an audience of school pupils (sometimes working within a classroom setting). The problems featured are designed to be more challenging than those typically found in textbooks. Mathematical ideas are often presented in new or unusual contexts so that a problemsolving strategy (Piggott 2005) for a particular problem may not be immediately obvious. In a classroom setting, where problem-solving is taking place there is often a lot of mediation by the teacher at the start of lessons in which they prepare students for what they are about to do and on-going support that offers clarification and prompts. This feature of classroom life is not available to students tackling problems from the NRICH website independently. We were interested to know if it is possible to support such pupils in “stepping into” problems which appear unfamiliar on a website like NRICH without diminishing the challenge for users to think for themselves. Concept mapping is a heuristic device developed by Novak and Gowin (1984), which involves the pictorial representation of concepts as individual nodes, linked together within a hierarchical structure. The aim of this study was to explore whether this technique might be an effective means of ‘stepping’ children into the kinds of problems found on the NRICH website, which may at first seem difficult or which they may be unsure how to approach. Three classes of Year 6 children were recruited from three local schools. Three one hour sessions were spent with pupils working independently on three problems interspersed with an instruction session on the use of concept maps: one pre-test problem (without using concept maps), instruction two post test problems (with concept maps). Data was also collected in the form of a questionnaire on pupils’ views on the value of the concept map in supporting their problem solving. The data confirmed that the children did not find the CMs to be particularly useful. Interestingly, however, response was more favourable when pupils were asked whether they felt CMs to be useful for solving maths problems generally. It may be that we were not successful in selecting problems that lent themselves well to concept mapping, despite our efforts so to do. It is also possible that the thirty minutes of instruction and one example problem were not adequate to achieve the level of understanding necessary for 1 children to make effective use of the maps. Response to a questionnaire item asking how well children felt they understood concept mapping almost half of the children (48%) reported understanding concept mapping ‘well’ or ‘very well’. About the same proportion of children (47%) said they felt they had learned enough to make a CM on their own. The feedback received from the participating pupils, along with the fact that almost no maps were actually produced, would suggest that concept mapping would not be an appropriate mediation tool for the NRICH website. References Novak, J. & Gowin, D.B. (1984) Learning How to Learn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Beardon, T. (2003) A Short History of NRICH, Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. Piggott, J. (2005) An investigation into the nature of mathematical enrichment: a case study of implementation. Thesis for Doctor in Education, Institute of Education, London. 2

![afl_mat[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005387843_1-8371eaaba182de7da429cb4369cd28fc-300x300.png)