Understanding possible changes in EBV`s for Southern Africa

advertisement

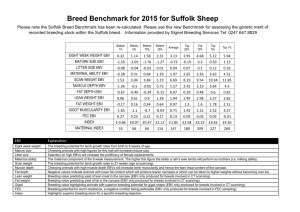

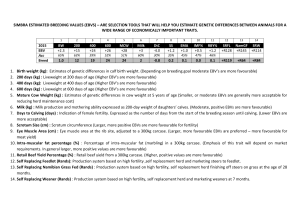

Understanding possible changes in EBV’s for Southern Africa Simbra (Johan Potgieter) The accuracy associated with a breeding value (EBV) gives an indication of its reliability and the likely extent of its possible change as more information becomes available. EBVs are based on the available information at the time of the genetic analysis. As more data becomes available on an animal (or its progeny, or relatives) then the accuracy of its EBVs for particular traits will increase. For example, a bull at 18 months of age might have EBVs based on his own performance and the performance of his siblings, parents and other relatives. As the bull is used, and his progeny recorded, more information is available about his likely genetic merit. As a result, his EBVs may change and the accuracies will increase. Accuracy are influenced by the heritability of a trait and the genetic associations existing between traits. For low heritable traits, more information is required to achieve a similar accuracy to that of highly heritable traits. Accuracies are expressed as percentages. The higher the percentage, the greater the chance that the EBV is a close estimate of the animal’s true genetic merit, and the less the likelihood that the EBV will change as more information becomes available. Even though an EBV with a low accuracy may change in the future, it is still the best estimate of an animal’s genetic merit for that trait. Generally, as more information becomes available, an EBV is just as likely to increase as it is to decrease. The maximum likely change to EBVs at different accuracy levels is indicated by the standard error associated with different accuracies. The magnitude of the standard errors decrease as the accuracies increase. Statistically, there is a 68% chance that an animal’s true breeding value will be within 1 standard error of its EBV, and a 96% chance that it will be within 2 standard errors of the EBV. Table 1. Confidence ranges 1 (standard error) for EBV's at different levels of accuracy for Southern Africa Simbra Trait Gestation L. Birth Wt. 200−day Wt. 400−day Wt. 600−day Wt. Cow Weight Carcase Wt. Carc Rib Fat Carc Rmp Fat Carc EMA Carc RBY % Carc IMF % Scrotal size Days to Calv 200 Wt Mat. 0.50 2.1 2.4 9.2 13.2 16.9 27.4 9.8 1.8 2.2 2.3 1.4 0.7 1.3 0.7 7.3 6.2 0.55 2.0 2.3 8.9 12.7 16.3 26.4 9.4 1.7 2.2 2.2 1.3 0.6 1.2 7.0 6.0 0.60 1.9 2.2 8.5 12.2 15.6 25.3 9.1 1.6 2.1 2.1 1.3 0.6 1.2 6.7 5.8 0.65 1.8 2.1 8.1 11.6 14.8 24.0 8.6 1.6 2.0 2.0 1.2 0.6 1.1 6.4 5.5 0.70 1.7 1.9 7.6 10.9 13.9 22.6 8.1 1.5 1.8 1.9 1.1 0.6 1.0 6.0 5.1 Accuracy 0.75 0.80 1.6 1.4 1.8 1.6 7.1 6.4 10.1 9.2 12.9 11.7 20.9 19.0 7.5 6.8 1.4 1.2 1.7 1.6 1.8 1.6 1.0 0.9 0.5 0.5 1.0 0.9 5.6 5.1 4.8 4.3 0.85 1.3 1.4 5.6 8.0 10.3 16.7 6.0 1.1 1.4 1.4 0.8 0.4 0.8 4.4 3.8 0.90 1.0 1.2 4.7 6.7 8.5 13.8 4.9 0.9 1.1 1.2 0.7 0.3 0.6 3.7 3.1 0.95 0.7 0.8 3.3 4.8 6.1 9.9 3.5 0.6 0.8 0.8 0.5 0.2 0.5 2.6 2.3 0.99 0.3 0.4 1.5 2.2 2.7 4.5 1.6 0.3 0.4 0.4 0.2 0.1 0.2 1.2 1.0 1 Statistically there is a 68% chance that an animals true breeding value will be within 1 standard error of its EBV and 96% chance that it will be within 2 standard errors of its EBV. For example, a 200d EBV with an accuracy of 90% will have a standard error of ± 4.7 kg. If an animal’s 200d EBV is +25 kg, then with the addition of further information (e.g. progeny or sibling records), the EBV would be expected to fall within the range of +20.3 kg to +29.7 kg (i.e. 25 kg ± 4.7 kg) 68% of the time; and within the range of +15.6 kg to +34.4 kg (i.e. 25 kg ± 9.4kg) 96% of the time.